The Williams Family and Neighboring Communities

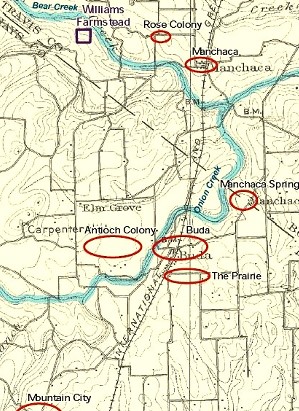

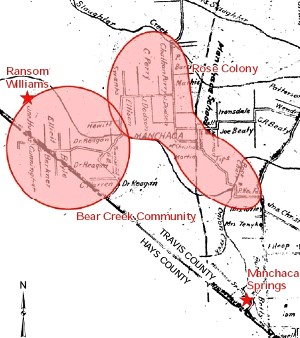

Circa 1880 map of Hays County and northern Travis County showing the John McGehee League and first landowners and communties. A pioneer in the area, Ransom Williams purchased his land south of Bear Creek in 1871. For many years, the family lived in this remote area, surrounded by white neighbors. Enlarge image to learn more. View map of landownership in McGehee League in 1873. |

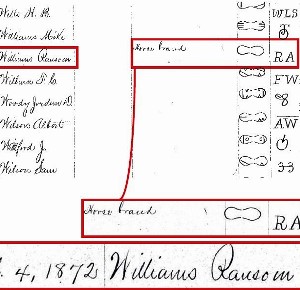

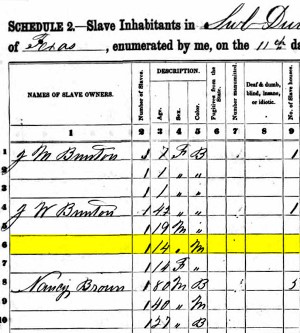

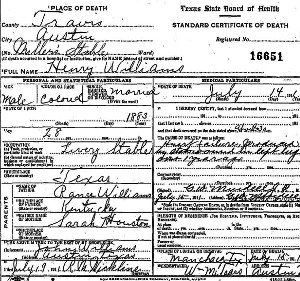

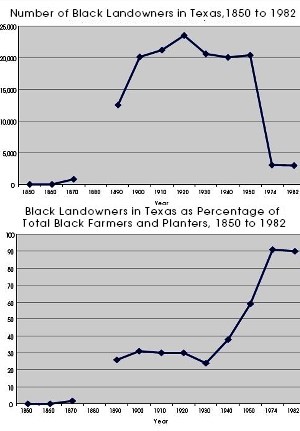

Little is written about the freedmen farmers who settled in northern Hays and southern Travis counties after the Civil War. Most were hardworking farmers of humble means.They left few records of their accomplishments and many of their children eventually left the farms for towns and cities, cutting their ties to the land. Of the many yeoman farmers who broke land, planted fields, raised families, and eked out an existence in this area, Ransom Williams is one of the most enigmatic. His race, heritage, and association with other settlers in Hays and Travis counties remained clouded by missing documentation or conflicting records. His name was absent from census records his entire life. In this section, we weave together what has been learned about Ransom and his family based on a variety of documents and archeological evidence. While an overall picture of their lives can be constructed, a number of details remain a mystery. Ransom and Sarah Williams raised their family on a small farm in southern Travis County in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Unlike many of their fellow freedmen, they were able to purchase the land for their farm. Owning property brought them a degree of freedom and independence that must have felt amazing: as slaves, they themselves had been owned as property, and they had had no legal identity. Ransom and Sarah settled in a rural section of Bear Creek, surrounded by white neighbors. While they were probably friends with some of their neighbors, they lived in a racially segregated world and the community to which they truly belonged was not on Bear Creek. Their social lives were tied to their African American friends, neighbors, and relatives through school, church, and other social institutions, first at Antioch Colony and later at Rose Colony–Manchaca. Initial Settlement of the AreaIn 1871, Ransom Williams purchased a 45-acre tract of land in the John G. McGehee League, which straddles the Travis-Hays County line about 12 miles south of Austin. The league remained a virtual wilderness—the land was unbroken and inaccessible by road—until after the Civil War, when brothers Charles and David Word subdivided the land into 40-acre parcels and advertised them for sale. The postwar era was ripe for land sales in central Texas as the state attracted thousands of people, particularly Southerners, displaced by the war. Williams was one of the first inhabitants of the league. Except for his neighbor, John Wilkins, Williams was entirely isolated in 1871; there were no roads, no bridges, no farms, and no easy access to dry goods or mills. Williams paid Word $160 in cash and a promissory note for $20, buying his farm for $4.00 per acre. It is unknown how Williams, a freedman just six years out of slavery, obtained enough money to buy his farm. There is no evidence that Williams was assisted by the Freedmen’s Bureau, but Hays County tax records show that Williams had acquired quite a few horses by the the end of 1860 and then registered his “horse brand” with Travis County in 1872. Once he bought the Travis County land, he paid taxes on fewer horses, suggesting that he sold some of his horses to raise cash to buy the land. Ransom probably began to work his land soon after his 1871 purchase, if not before, but by early 1876 he was married and had his first child. As a landowner in the 1870s, Ransom was one of the lucky ones because only a small percentage of black farmers owned property; most were tenant farmers, sharecroppers, or wage laborers. Tracing the Williams FamilyWe know a great deal about some aspects of Ransom and Sarah’s lives, but we know very little about other parts of their history, especially their lives prior to emancipation. Ransom Williams and Sarah Houston married in about 1875 and had nine children over the next few decades. Together they operated their small farm in southern Travis County. Ransom Williams is intriguing for a number of reasons. He was almost certainly an emancipated slave and possibly a mulatto who on occasion passed for white. Like many former slaves, he never learned to read or write but rather used an “X” to mark his name on legal papers. Despite this, he managed to buy and improve his own property, build a house, take a wife, make a living, and raise nine children, at least four of whom (Will, Mary, John, and Emma) attended school and gained literacy. Little else is known about Ransom’s pedigree or heritage; the man left no written records and managed to avoid the census taker his entire life. What we do know about Ransom Williams and his family stems from archeological investigations and a variety of historical documents, including deed, tax, brand registration, and voter registration records. From the documents, we know that Ransom was born in Kentucky on or before 1846 and arrived in Texas by 1866. He was identified as “colored” in the 1867 Hays County Voter Registration rolls and was almost certainly a freed slave. In the late 1860s, Ransom lived in or near the freedmen community called Antioch Colony in northern Hays County. Some of the founders of this community were former slaves of the Bunton brothers who came to Texas from Tennessee and Kentucky in the 1840s and 1850s. Williams’s first name suggests that he might have been related to one of the Bunton slaves, Ransom Bunton Sr., who lived near Antioch after emancipation. Williams’s association with the Bunton freedmen, his first name, his Kentucky origins, and his residency in northern Hays County after the war, suggest that Williams may have been one of the Bunton slaves. Further evidence of a connection between the Williams and Bunton families is found in the 1930 census, when one of the Ransom and Sarah’s daughters, Mary Davis, was living in Austin with a cousin named Emma Bunton. Although the evidence is circumstantial, one archival record perhaps documents Ransom Williams as a boy. In the 1860 slave census, a 14-year old boy is listed among the 23 slaves owned by the Bunton brothers who operated the Mountain City Plantation in northern Hays County (near the modern-day town of Buda). This teenage boy was listed as a mulatto (the child of a white and a black parent) owned by John Wheeler Bunton, the patriarch of the Bunton family who had come to Texas in the 1830s. John Wheeler Bunton was one of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence, and he served in the House of Representatives of the First Congress of the Republic of Texas in 1836. The evidence is compelling, suggesting that this young slave boy, who would have been born around 1846, would later become the freedman named Ransom Williams. During his life with the Bunton family, with their roots in the horse-breeding state of Kentucky, he likely acquired the skills and knowledge required to raise the animals himself. We know that Ransom died in or around 1901, but we found no death certificate and do not know with certainty where Ransom was buried. During the archeological investigations, we found no evidence of a possible gravesite. Had he been buried on the farm, the grave marker was probably wooden and could have disappeared long ago. However, the discovery of Sarah William's gravesite in an African-American cemetery in San Marcos raises intriguing questions about possible unmarked graves nearby, one of which might be Ransom's burial site. See Searching for the Gravesites of Ransom and Sarah Williams. Archival documents reveal some important facts about Sarah Houston. She was born in 1851, was a mulatto, and was almost certainly a slave. The 1850 census records show that out of 58,558 African Americans living in Texas, only 397 were free blacks and the other 99.3 percent were enslaved persons. Statistically speaking, the chance that Sarah Houston was not born into slavery is extremely low. From her death certificate, we know that Sarah Williams was born somewhere in Texas and lived to be “about 70” years old; she was listed as a “Negro” and a “Widow.” She was living in San Marcos, Texas, when she died on March 11, 1921, and was buried there. From the death certificates of five of her children, we know that Sarah Williams’s maiden name was Houston and that she was married to a Kentucky-born man named Ransom (also shown as “Rance” or “Ransome”). Unlike Ransom, Sarah Houston does show up in the 1870 U.S. census when she was recorded as a 15-year-old African American girl living in Austin. Since no other Sarah Houstons were recorded in the entire state of Texas at that time, it is almost certain that this was the girl who later became Ransom’s wife. According to this census, Sarah was single, born in Texas, and worked as a live-in servant for the white Albert Roberts household. Roberts was a merchant and grocer from Virginia, and he had five other black servants named Tisdale residing at his address. The 1872 Austin City Directory shows that a family of black Houstons lived only four doors away from the Roberts family, and it is possible that Sarah was related to them in some way. Notably, no other Houstons were listed for Hays County or Southern Travis County in the 1870 census. Sarah Houston also appears in an 1875 census taken by the City of Austin. According to this census, Sarah was a 21-year-old woman, “colored,” lived on Cypress Street (now Third Street), and worked as a cook. Sarah Houston does not appear in any subsequent Austin records, most likely because she married Ransom Williams and moved out of the city soon after the 1875 census was taken. When we discovered that Sarah’s maiden name was Houston, we were intrigued by the possibility that she might have been a slave owned by Sam Houston, who lived in Austin during his short term as Governor of Texas from December 1859 to March 1861. After an exhaustive search, however, we found no evidence that would link this Sarah Houston, born a slave in 1851, with Sam Houston. We do not know how, when, or where Ransom and Sarah met, and it is likely that no marriage certificate was ever issued. Mutual friends might have introduced them to each other, perhaps at a church service or a social gathering such as a Juneteenth celebration, or it might have been a random meeting on the streets of Austin. The details will probably always remain a mystery, as none of the family descendants that we interviewed knew much about their great grandparents. Because of this, our knowledge of Ransom and Sarah’s lives together begins with their children. Some records indicate that Ransom and Sarah had nine children, but only seven of them are accounted for: William (Will), Charles (Charley), Mary, Henry, Mattie, John, and Emma. It is possible that the two missing siblings died as infants or young children, and their names never made it into any official records.

|

|

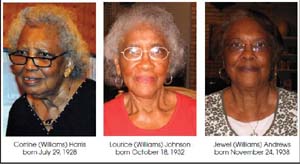

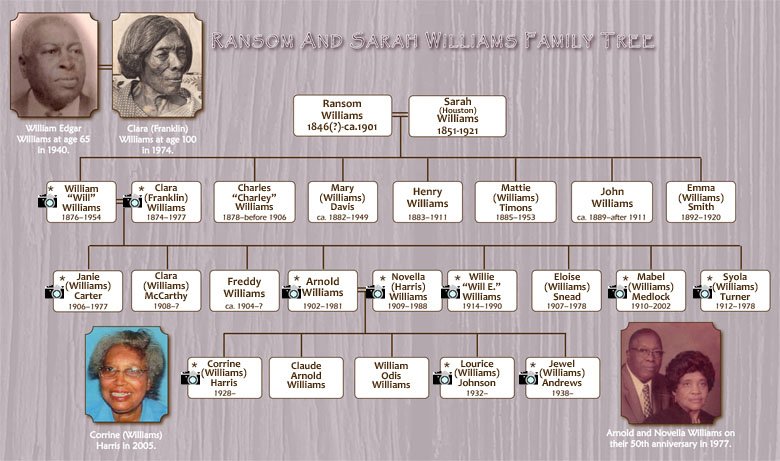

In the course of our research, we traced four generations of the Williams family, from Ransom and Sarah in the late nineteenth century to five great grandchildren who were still living in Austin and Houston. Although no photographs of Ransom or Sarah have been found, it is interesting that one of Ransom’s grandsons, Arnold Williams, bore a close resemblance to his father, William (“Will”). Perhaps Ransom Williams looked like Will and Arnold? This family tree was constructed from various sources of information, including census records, death certificates, and interviews with three great granddaughters of Ransom and Sarah Williams—Corrine Harris, Lourice Johnson, and Jewel Andrews. |

|

It was common for late-nineteenth-century farm families to have many children, and one historian noted that "the average black farm woman in the South" had nine children. Sarah Williams, thus, was typical in this regard. She was about 25 years old when she had the first child and 41 or 42 years old when her last was born. For the Williams family, running a successful farm for almost three decades had to have been a family affair, with the children playing important roles in operations. As soon as a child was old enough to walk, he or she was probably given household and farm chores to do. Their responsibilities increased as they grew older, and by the time they were 9 or 10 years old, they would have been expected to help raise their younger siblings, feed the pigs and chickens, collect eggs, and wash dishes. Older children took on some of the harder chores, such as working with the horses and cattle, hauling water, chopping firewood, and repairing fences. Unlike other African Americans living in freedmen settlements, however, the Williams family likely had to travel farther for assistance from neighbors and community support. Early Neighbors in the Bear Creek and Rose Colony CommunitiesIn 1875, Ransom and Sarah Williams were the only African Americans living on Bear Creek. The Williams' first neighbors were a handful of white farmers who plucked up the undeveloped parcels around him, south of Bear Creek. John Wilkins, Daniel Labenski, the Murphys, and the Townsleys were pioneers on the south side of Bear Creek. These earliest settlers in the McGehee League had no easy access to stores, blacksmiths, machinists, doctors, schools, or churches—the basic amenities that defined communities at that time. The city of Austin lay about 12 miles to the north, and the rural community of Mountain City, in northern Hays County, lay about 6 miles to the south. However, there were no established roads leading to the Bear Creek settlements. As far as we know, there was never any church, school, or store in the Bear Creek area that would have served as a community anchor. Nevertheless, these early pioneers endeavored to form a community of like-minded farmers in the 1870s. Because of his race, Ransom Williams was probably excluded from many activities in the Bear Creek rural community, especially social events. When other freedmen started moving into the nearby Walker Wilson and S. F. Slaughter leagues in the 1870s, Williams and his family likely associated with them. A community of black farmers began to coalesce between Bear Creek and Slaughter Creek by the mid- to late-1870s. Among these pioneers were Ben Van Zandt, Chatham Perry, Richard Washington, and John Rose. These families were the core of the freedman community of Rose Colony, which later became the African American section of Manchaca, a town which sprang up after the railroad was extended from Austin to San Marcos in 1880. Other African American families who came to the Bear Creek-Rose Colony-Manchaca area were Alexander, Coats, Dodson, Dotson, Hargis, Hughes, Pickard, Owens, Scroggins, Slaughter, and Sorrells. These first African American farmers in the Bear Creek-Rose Colony area were true pioneers. They were newly freed from bondage yet somehow managed to buy their own land. It was poor quality, upland farmland in a raw wilderness, but it was their land nonetheless. For the first time, they were able to make life decisions and govern themselves. They married with the assurance that their families would not be sold away. They owned their own land and labor. They formed their own associations—churches, schools, and fraternal organizations—for inspiration, education, and the betterment of their created community. During the 20 years between Ransom Williams' land purchase in 1871 and the arrival of the Dodsons in 1891, the pioneers of Bear Creek-Rose Colony joined together to form the framework for their own community, one of several hundred such "Freedmen's Colonies" in Texas. In her book, And Grace Will Lead Me Home: African American Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865-1928, Michelle Mears states that rural freedmen formed remote, scattered, informal, and unofficial communities in rural areas throughout the state by the last years of the nineteenth century. This pioneer generation succeeded in establishing a fledgling community for later African Americans who came to live in south Travis County. In the 1870s, Ransom and Sarah Williams and their small children probably socialized with residents of the Antioch Colony, the freedmen settlement that had emerged in the Mountain City area during the late 1860s. The colony was 4.5 miles south of the Williams property, in northern Hays County. While some other African Americans lived on the east side of Onion Creek, the Antioch settlement was the only established freedmen's community in northern Hays and southern Travis counties when Ransom and Sarah Williams first came to the farm. Comprising 12 to 15 extended families, the community provided a church, a school, and social opportunities that were unavailable to the Williams family in the Bear Creek community of the 1870s. |

|

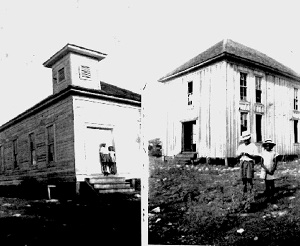

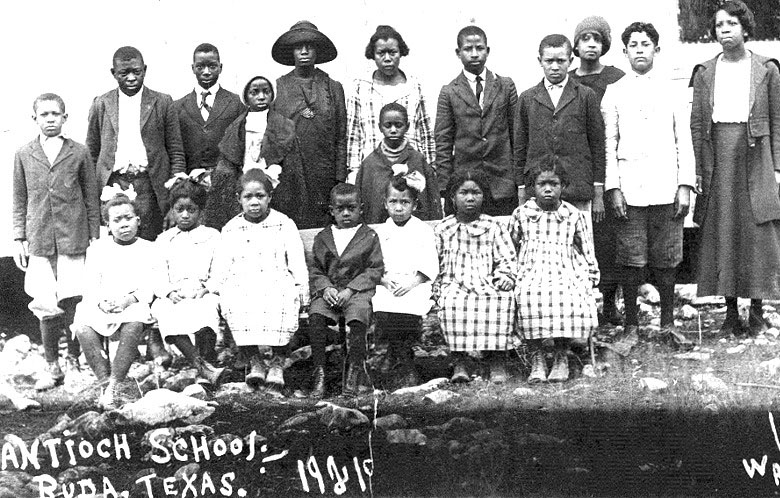

The 1921 school class at Antioch Colony. Most rural schools at the time, for blacks or whites, consisted of one or two rooms and a single teacher for all the grades. While the educational opportunities were supposed to be equal for blacks and whites in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, studies have shown that the monetary value of the school buildings and other resources for black students were consistently lower than those of their white counterparts. For the Antioch Colony students in 1921, life was probably not much different than it had been for the Williams family children when they were students in the 1880s and 1890s. Photo courtesy of LeeDell Bunton, Sr. |

|

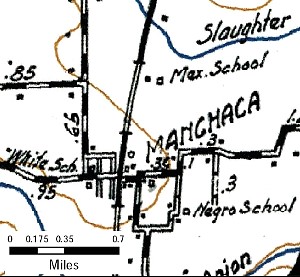

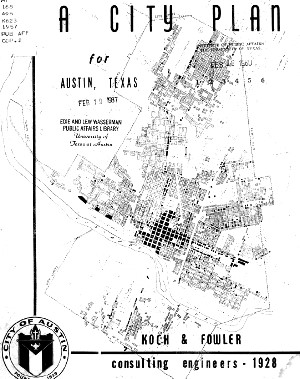

Rose Colony had its own school for African American children by 1877, and it probably hosted church services on Sundays as well. Because it was closer to the Williams farmstead, it may have supplanted Antioch Colony as the base community for the Williams family. By the time the first of the Williams children were of school age, around 1882, the Rose Colony School (originally called Union Grove School) for African American children had been in operation for five years. From deed records, it appears to have been about 2 miles to the east of the Williams farm, and in the area that grew into the town of Manchaca. The school was likely the focal point of African American life in southern Travis County, drawing students from throughout County Precinct 5, which spanned much of the Bear Creek, Onion Creek, and Slaughter Creek watersheds. For the parents, few of whom could read or write, education represented an opportunity for their children to get ahead in the world. A decade after the school was built, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church was erected on an adjacent half-acre of land in the Slaughter League, and within the community of Manchaca. Today, the AME Church is represented by the New Bethel AME Church on Manchaca Road. This congregation dates its origins to Jack Dodson's 1891 AME Church. Changes in the Twentieth CenturyIn the first decade of the twentieth century, a series of events occurred in the Williams family which were to influence the family's decisions for the future. Ransom Williams was probably 55 years old when he died about 1901, and this certainly changed the family dynamics. Central Texas also experienced a severe drought in 1901, and the added stress of dealing with this might have contributed to Ransom's death. The two oldest boys, Will and Charley, were the farmers in the Williams family, and they had purchased 12 acres of land immediately west of the original 45-acre homestead in 1900. But a year later, Will married Clara Franklin, and the couple moved to Creedmoor to be near Clara's family. The next oldest boy, Charley, may have died between 1904 and 1906, as he is absent in all subsequent records. We know that Sarah left the farm by about 1905 and moved to east Austin along with her two youngest children, John, who was about 16 years old at the time, and Emma, aged 13 or 14. Along with the records, this history is corroborated by archeological evidence that indicates no one was living at the Williams farmstead after about 1904. Although they no longer lived on the farm, the Williams family continued to own their land for three more decades. They might have farmed the land themselves or leased it to someone else, perhaps one of their neighbors. In 1934, however, the family sold the original farmstead property, and in 1941, the adjacent property. Like many thousands of blacks throughout the South, the Williamses gave up the rural farm lifestyle in the twentieth century and became urban city dwellers. Three of the great grandchildren of Ransom and Sarah Williams grew up in East Austin and still live there. Corrine Williams Harris, Lourice Williams Johnson, and Jewel Williams Andrews were active informants in our oral history project, and their recollections bridge the gap between rural life at the Williams farmstead and urban life in East Austin. They are descendants of Ransom and Sarah's oldest son, Will, and his wife Clara. Before the project, they knew little about their great grandparents' lives on the farm. The African American community at Manchaca thrived into the twentieth century, and some things changed very little. School and church remained the anchors that tied the people of the community together. Robbie (Dotson) Overton, who was born in Manchaca in 1935, remembered attending "an all-black school, one-room school" where "one teacher taught everything." When asked what religion and church meant to her family growing up in Manchaca, Earselean (Sorrells) Hollins stated that "We grew up in church. It was important to me basically because we could all get together, we'd see other people besides our regular family members. We played ball, and then we'd have lunch on the grounds. It was just a fun time." Jim Crow and Racial DiscriminationNo history of a freedman family in Texas would be complete without a frank discussion of the racial discrimination that was codified all across the southern United States by Jim Crow laws. For Ransom Williams and Sarah Houston, emancipation offered the hope of equality for freed blacks, but the harsh realities set in when the promises failed to materialize by the end of Reconstruction. After the U.S. Army ceased to enforce Federal law in the state, discrimination and the threat of violence against blacks increased. Racial discrimination was a fact of life for the Williams family in late-nineteenth-century Travis County as it was all across the South. Schools and churches were segregated, and African Americans were not allowed to take part in many social or political activities. Too easily, African Americans could be accused of crimes and severely punished or executed without being given due process of law. Lynchings were reported in Texas and across the south. As defined by historian John Ross, "Lynching is the illegal killing of a person under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition. Though it often refers to hanging, the word became a generic term for any form of execution without due process of law." The violence often began because a black person offended a white person or was accused of a crime with little or no evidence. Against this backdrop of racial segregation, discriminatory laws, and the constant threat of racial violence, the Williams family apparently kept a low profile, and their farm was a safe haven located well off the beaten path. While Ransom Williams and his family worked hard to become successful farmers, such success could have caused considerable animosity from many in the white population. When the family moved to East Austin early in the twentieth century, they faced a more codified type of discrimination. For many years, the white leaders in the city of Austin debated how to deal with the negro population. Although it was progressive in many ways, the City of Austin wanted to keep its black population segregated into East Austin and took formal steps to do so. In 1928, an engineering firm working for the city came up with a solution that was published as the City Plan for Austin, Texas. The plan reinforces the degree of racial discrimination that existed in Texas and across the South. The authors of the City Plan noted that “negroes” lived in small numbers all over the city but were most concentrated in a specific area of east Austin. They decided that this area should be established as the city’s “negro district". In effect, the Williams family traded the forms of racism common in rural areas for an urban variety of racial discrimination.

|

|