Memories of the Past: Oral History, Archeology, and Community Involvement

Forebears and familiy members from Antioch Colony and nearby communities, including Eliza Bunton, Carrie Dotson, and Ike Brown on their front porch; Addline (Kavanaugh) Bunkley,who was born ca. 1849; Joan Limuel in graduation cap; Emily Harper; a very young LeeDell Bunton with playmates Moses Ollie Joe Harper and Samuel Leslie Harper; and Bert Williams with a load of cotton pickers in the truck. Images from "I'm Proud to Know What I Know: Oral Narratives of Travis and Hays Counties, Texas, ca. 1920s-1960s" by Maria Franklin. Photographs courtesy of Earlee Bunton, LeeDell Bunton, Sr., and Joan Limuel. |

|

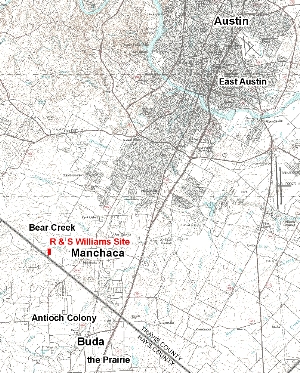

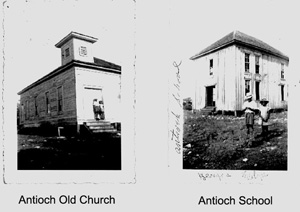

Why are oral history interviews important in an historic archeological project? How do the memories of twentieth-century informants relate to the historical archeology of a nineteenth-century farmstead? In the case of this project, the answer is simple. The oral history stories that we gathered and the archeology of the Williams farmstead are intimately related. The oral history, historic documents, and archeological remains represent different types of evidence used for the same basic purpose—to reconstruct an accurate historical narrative of African American life. The historic documents and archeology tell the first half of the story, detailing the lives of the Williams family members from the antebellum period through the turn of the century. The oral history narratives tell the second half of that story, following the lives of many people who lived similar farming lifestyles in the early twentieth century and documenting how the Williams descendants and others transitioned to an urban life after they abandoned their farms. In many cases, there are significant overlaps between the oral history and the archeology because the interviewees were following social and cultural practices that were passed down to them by their elders. For our part, we wanted to share the history and archeology of the Williams farmstead site with the descendant community, in particular, and to raise public awareness of African American history in Texas. The oral history project we initiated in 2009 helped us to address these concerns. To start, it enabled us to open lines of communication with people who were interested in our research. Most of the individuals we eventually spoke with had deep roots in Travis and Hays counties and identified closely with the local history. Given this, it was important to ensure that their personal and collective memories would become a part of the larger historical record. In all, we formally interviewed 27 individuals who were raised in Austin, Buda (Antioch Colony and the Prairie), and/or Manchaca. All are part of the broader descendant community in this region who are historically connected to and invested in the area’s past. Project BackgroundWe began outreach efforts locally and were fortunate in that people generally responded favorably to interview requests and were open to sharing knowledge about themselves and their family’s history. All of the interviewees were “project stakeholders,” having spent at least part of their youths near the Williams farmstead. The majority recalled what rural life was like when most people farmed for a living and easily related to what the archeology revealed about the day-to-day experiences of the Williams family. In terms of finding people to interview, for some we had nothing more than a surname identified in archival records to start with. Internet searches and the phone book garnered some success. Most of our outreach, however, relied on word of mouth to raise visibility of the project, and to locate more potential interviewees. A prime example of this was our outreach with the Manchaca/Onion Creek Historical Association (MOCHA). Our project historian, Terri Myers, posted a flier at the Manchaca Post Office as part of our efforts to locate potential interviewees and Williams family descendants. A MOCHA member responded, and over the course of this project the group visited the Williams site excavation and hosted lectures by our project team members. Sharing our research proved to be productive for both the project team and MOCHA. Marilyn McLeod’s ancestor, Victor Labenski, was a neighbor of the Williams family. It was McLeod who contacted KLRU producer Michael Emery and told him about our project, which led to its inclusion in the 2010 Juneteenth Jamboree program. Thanks to MOCHA we were also able to find more interviewees. This included MOCHA members Joanne Deane and Lillie Meredith Moreland, both longtime residents of Manchaca/Bear Creek and descendants of the area’s earliest non-native settlers. Deane and Moreland were able to provide an account of life in the area from the perspective of Euro-American descendants. Narrators of the PastMost of the interviewees hailed from Buda, located roughly 5 miles south of the Williams site. Following on the heels of emancipation, freedmen purchased land there and founded Antioch Colony. During her archival research, historian Terri Myers discovered a likely kinship connection between the Williams family and the Buntons of Antioch. During the 19th century, this settlement was the largest all-black enclave near the Williams farmstead and boasted its own church and school. Undoubtedly, Ransom and Sarah knew of Antioch. Since there are descendants of the 19th-century settlers currently living in Antioch Colony, it was not difficult to find people who were interested in learning more about the project, and who wished to be interviewed. Likewise, narrators who were born in Manchaca—just a couple of miles from the Williams farmstead—expressed deep sentiments about their local heritage. It is very likely that the Williams family went to church with the parents and grandparents of some of our interviewees The remainder of our interviewees called east Austin home, including direct descendants of the Williams family. The capital city’s east side has historically been largely African American, at least since the late 1920s when city authorities strategized to segregate blacks to that section of town. It was around this time when African Americans across the South relocated to cities in large numbers in search of jobs or to further their education. Since Austin was the urban hub of central Texas, every interviewee spent time there at some point. Of the 27 narrators, 25 were African Americans and two were Euro-Americans. The majority of them were women (20 of the 27) and most of the narrators were over the age of 70 years at the time of their interview. Over half of them grew up in farming households either as landowners, tenant farmers or sharecroppers. We interviewed direct descendants of the Williams family, the great granddaughters of Ransom and Sarah. They are Jewel Andrews, Lourice Johnson, and Corrine Harris. We also co-produced oral histories with the following individuals, several of whom passed away before the project was completed: Anthy Lee Walker (d. 2010); Estella Black; Robbie Overton; Moses Harper, Sr. (d. 2009); LeeDell Bunton, Sr.; Samuel Harper; Essie Mae Sorrells (d. 2012); Lillie Moreland; Joan Limuel; Ruth Fears (d. 2012); Marcus Pickard, Jr.; Kay Randall; Winnie Moyer; Earselean Hollins; Annie Axel; Floris Sorrells; Lillie Grant; Lee Dawson; Rene Pickard; Joanne Deane; Cedel Evans; Earlee Bunton; Minnie Nelson; and Marian Washington. Stories of Family and Community in Travis and Hays Counties, 1920s-1970sDuring recording sessions, narrators mainly recalled their experiences growing up in central Texas. While we discussed a wide range of topics, family life emerged as a major theme. Narrators talked about their relationships with various family members, and expressed why their parents and grandparents were cherished role models. For most, since living out in the country required hard work, narrators also spent time relating how their families were largely self sufficient. In particular, they singled out their mothers and grandmothers, remembering how they took care of the house, nurtured their children, and picked cotton alongside their husbands and children. Many women also worked for white families, taking in laundry, cleaning house and cooking, and caring for children. Despite the hardships, however, narrators remembered happy childhoods and were thankful for the values that were instilled in them. |

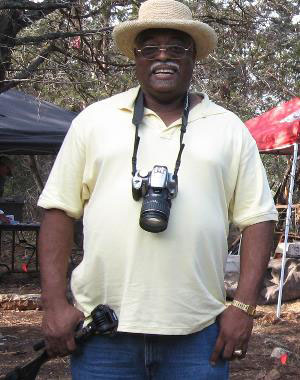

Members of the descendant community tour the Williams farmstead site with archeologists.

The archeology of the Williams farmstead tells an amazing story of a successful farm family, but the story ends rather abruptly when the family left the farmstead in 1905. The story might have ended there if not for the oral history interviews conducted by University of Texas Professor Maria Franklin and her graduate student, Nedra Lee. Recollections of the interviewees helped archeologists draw connections to the farmstead evidence. View video and learn more

In this video clip, LeeDell Bunton, Sr., a descendant of the founding settlers of Antioch Colony, talks about the connection between the archeology of the Williams farmstead and the history of the freedmens colony. Bunton worked with members of the research team and helped to make the oral history project and public outreach efforts a success. Video clip courtesy of Instructional Technology Services (ITS), University of Texas at Austin.

Lillie Meredith Moreland (left) and Joanne Deane (right). Photo taken in Manchaca, Austin, in 2009.

In this audio clip, Lillie Meredith Moreland and Joanne Deane recall the Depression and how people in Manchaca fared.

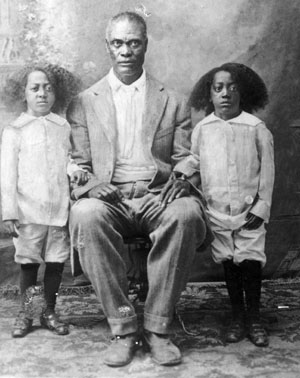

S. M. Sorrells with twin sons, Alvin and Virgil, date unknown (the boys were born in September 1910, so the photo dates to the early 1900s). S. M. Sorrells was one of the earliest African Americans to purchase land in Manchaca, property that is still held in trust by his descendants. Sorrells is the grandfather of interviewees Earselean Hollins and Cedel Evans, and the great-grandfather of Kay Randall. Photo courtesy of the children of Virgil and Essie Mae Sorrells.

|

Stories of Family and Community in Travis and Hays Counties, 1920s-1970s |

Robbie (Dotson) Overton, 2009.

In this audio clip, Robbie (Dotson) Overton expresses the importance of family and what her mother, Carrie (Bunton) Dotson, means to her. |

Carrie (Bunton) Dotson, the mother of Robbie Overton. Unknown date, Austin, TX. Photo courtesy of Robbie Overton. |

Estella (Hargis) Black, 2009. |

The birth family of Estella (Hargis) Black. From left to right (back row): Willie Jr., Lonnie, Otis, Bertha, Chatham, Estella. Front row: parents Maggie Perry Hargis and Willie Hargis. Photo courtesy of Estella Black.

In this audio clip, Maria Franklin interviews Estella (Hargis) Black (left). Mrs. Black discusses the diverse chores her parents undertook in order to feed the family, and how her mother made extra money by selling homemade butter. |

Samuel Harper, 2009. |

Winnie (Harper) Moyer, 2009. |

Emma (Tennon) Harper was mother and grandmother to a number of the oral history narrators, including Samuel Harper and LeeDell Bunton, Sr. Photo courtesy of LeeDell Bunton. |

|

In this audio clip, Samuel Harper states that although his father was the breadwinner, his mother, Emma (Tennon) Harper, worked hard to balance household chores with childrearing and picking cotton during harvest time. |

In this audio clip, Winnie Moyer talks about the sacrifices her mother, Emma (Tennon) Harper, made in working for white families in Buda, including being forced to use the back door during segregation. |

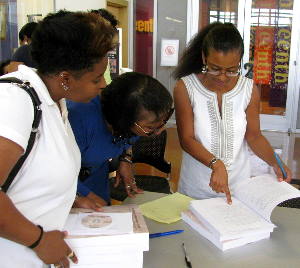

| In the African American communities that were founded following emancipation, churches and schools were of central importance. Thus, we asked narrators about the roles that these institutions played in their communities. Historically, the black church was the social and political bedrock of African American life, and it helped to engender community solidarity. Since freedmen understood that socioeconomic mobility hinged on education, they also prioritized the building of schools for their children. A number of those interviewed had attended the first schools built in Manchaca and Antioch Colony for black children. Narrators also fondly remembered Anderson High School in east Austin which was the only high school for African Americans in the region before integration. Since most of the narrators grew to adulthood prior to the civil rights movement, we asked questions about race relations. Some individuals related personal experiences of racism that was typical of the time period, especially—but not only—in the South. Narrators from Manchaca and Buda also contrasted their interactions with whites they were acquainted with versus how they were treated when they went to Austin for shopping or to visit family and friends. Everyone remembered the businesses and restaurants in town that African Americans frequented, especially on East 6th Street and on 11th and 12th Streets. There were other topics raised in the oral history interviews that helped to illuminate what African Americans experienced growing up in rural communities and urban enclaves where everyone knew one another and attended the same churches and schools. Narrators also talked a lot about specific activities that characterized rural households, like hunting for wild game, fishing, laundry days, getting fresh water, and so on. In doing so, they played an instrumental role in helping the researchers to better understand what the Williams family probably experienced living along Bear Creek during the late 19th century. The artifacts recovered from the site included a wide range of dishes and bottle glass, buttons, jewelry fragments and other clothing-related objects, tools, evidence of firearms, and so on. Interviewees often commented on the kinds of material culture that they and others used for different activities which gives archaeologists important insights into how to interpret findings from the Williams farmstead. For instance, the fragments of toys found at the site could be interpreted in light of how children were socialized into gender roles. A Wealth of InsightsThe narrators shared with researchers and the public a wealth of knowledge, memories, and insights of life in Travis and Hays counties during the first half of the 20th century. They have enriched the project and added depth and accuracy to our interpretations of the Williams farmstead site and of African American history in Texas following emancipation. Four of the oral history narrators—Mrs. Anthy Lee Walker, Mr. Moses Harper, Mrs. Essie Mae Sorrells, and Mrs. Ruth Fears—passed away over the course of the project. We were saddened by their passing, and all the more determined to ensure that their recollections would be shared with others. The oral history project culminated with the publication of the interview collection in its entirety in July of 2012. Titled, “I’m Proud to Know What I Know: Oral Narratives of Travis and Hays Counties, Texas, ca. 1920s—1960s,” the two-volume report contains full transcriptions of all the interviews along with introductory chapters by Maria Franklin (see Franklin 2012 in “Credits and Sources”). This research documents details of daily life that are not found in any other sources and is a treasure-trove of first-hand, personal accounts of rural and urban life for African Americans in central Texas. With funding from the Texas Department of Transportation, we were able to provide complementary copies of the two-volume report to interviewees and their family members. A book signing ceremony took place at the George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center in East Austin on July 19, 2012, and most of the narrators were in attendance. |

|

Ruth (Harper) Fears, 2009. |

In this audio clip, Franklin asks Ruth (Harper) Fears about the different toys that boys and girls played with when she was a child in Antioch Colony. Sadly, Mrs. Fears was one of several interviewees who passed away during the course of the project. |