19th-Century African American Newspapers:

A Window into Life in Central Texas

|

|

|||

|

|

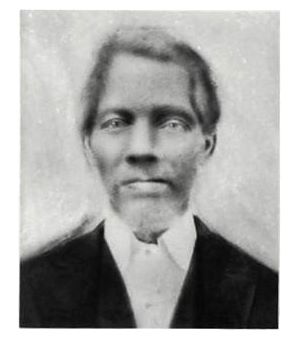

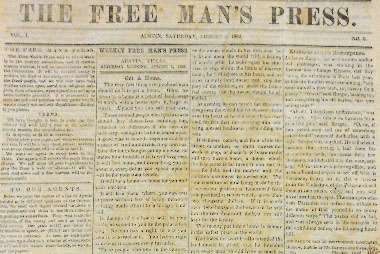

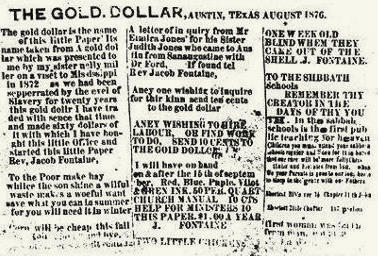

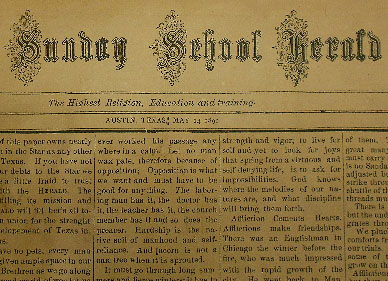

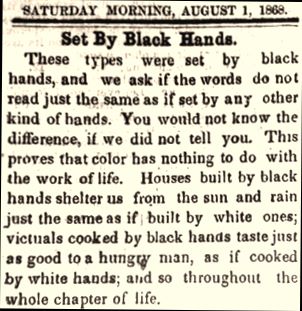

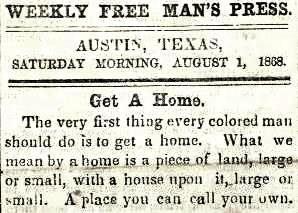

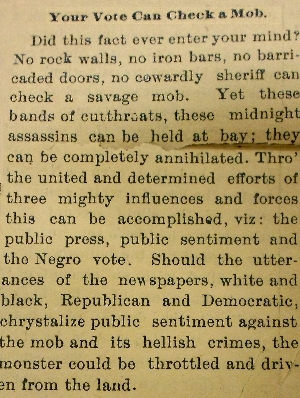

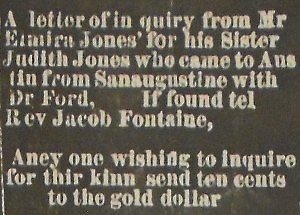

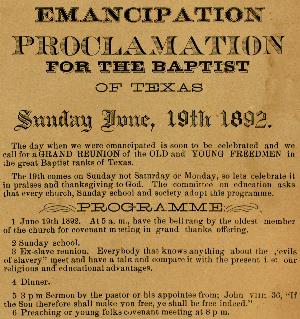

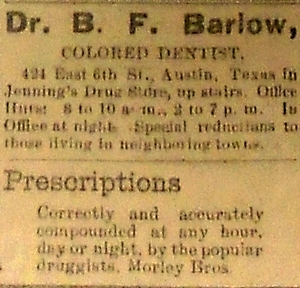

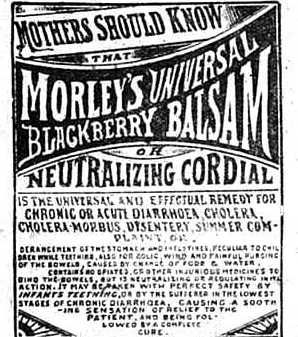

Rise of the African American PressIt is somewhat remarkable that we can peruse copies of the first black newspapers in Austin, as they were rare even in their day. Some papers were short-lived or had only sporadic publication runs. This can be attributed to the precarious nature of establishing and maintaining a black news publication following Emancipation. Many black newspapers quickly met their demise because of high rates of illiteracy, widespread economic impoverishment, and expensive operation costs. The success of black newspapers was also further hindered by racism. Black-run enterprises faced a lot of hostility from whites, and print shops were often vulnerable to violence and destruction if they challenged whites’ mistreatment of blacks. In spite of these challenges, however, the black press played an important role in the black community and received support from individual patrons, businesses, educational institutions, and religious congregations. Editors established black newspapers in direct response to white prejudice and exclusion. Black newspapers emphasized racial equality, social inclusion, and economic self-sufficiency. They discussed civil rights, the importance of black racial pride and religion, and the need for educational development. Correspondents specifically demanded an end to lynching and segregation as well as encouraged their readers to learn a trade and support black businesses. The importance of buying land and owning a home was also emphasized. In an article in The Free Man’s Press in August 1868, an anonymous author (probably the newspaper’s editor) summarized the general feelings about the freedom and security that came with owning a house and land. This article stressed that “A home will make the colored man a free man.” Black newspapers such as The Gold Dollar and the Herald emphasized religious and moral instruction and imparted dominant social mores and decorum. The editors printed religious sermons, anecdotes, scriptures and other notes on the Bible. For example, in an editorial in the Herald, Reverend Campbell expressed his displeasure at children’s behavior at a Juneteenth celebration. In The Gold Dollar, August 1876, shown above, Reverend Fontaine further warned parents, “But, train him up when he is young when he is old hiel [sic] not be Hung.” Moral instruction also went together with educational training; an example of this can be seen with the first and only issue of Reverend Fontaine’s paper. It contained the alphabet in upper and lower case letters, as well as various Biblical tidbits such as the numerical equivalent of currency listed in various chapters. Countering Negative PortrayalsThe black print media also worked to counter white journalists’ inadequate or negative portrayals of blacks in their newspapers since white writers either refused to cover black life or printed erroneous and racially biased stories. Black editors countered this problem with articles, correspondence and commentaries that extensively covered their communities’ participation in social activities as well as their central needs and concerns. The black press especially sought to debunk the myth of black men as rapists. As lynching increased, black newspapers included stories about mob violence and sought to present the facts behind white hostilities. The editors countered allegations that lynched black men had raped or assaulted white women, and correspondents often revealed that the motives behind lynching were often disputes over labor or money. Black editors boldly condemned mob violence, challenged other black newspapers to agitate against lynching, and demanded that suspects get a fair trial. They also urged their readers to register to vote and inform themselves about political issues and candidates, particularly those who would take action to prevent or check violence. An 1896 edition of The Searchlight carried the article, "Your Vote Can Check a Mob," stressing the importance of this civic duty, still new to and fraught with obstacles for emancipated African Americans. Notices and AdvertisementsEditors understood the importance of family to their black readers and included family search announcements in their newspapers. In journals such as the Gold Dollar, Free Man’s Press, and the Herald, people used these notices to announce their search for relatives from whom they were separated during slavery. The correspondents often looked for parents and siblings, and their searches listed the names of kin as well as their former slave owners. In one issue of the Gold Dollar, Reverend Fontaine offered to help subscribers locate missing kin for ten cents. It can be assumed that these searches were particularly important to Reverend Fontaine, who began his newspaper with a gold dollar that his sister gave him when they were reunited after a twenty-year separation because of slavery. In addition to helping families, Black newspapers also helped bind communities by publishing notices of celebrations, picnics, and other events. For example, a notice of upcoming Juneteenth celebrations, titled Emancipation Proclamation for the Baptist of Texas, was run in the May 21, 1892 edition of The Sunday School Herald. It read, in part, “The day when we were emancipated is soon to be celebrated and we call for a Grand Reunion of the Old and Young Freedmen in the great Baptist ranks of Texas.” Similar to the white print media, the black press relied heavily on advertising fees to sustain their operations. The newspapers sought to rally the support of black readers by emphasizing the importance of black patronage to continue their operations. Supporting black newspapers was evidence of race pride, and blacks were encouraged to read them, locate more subscribers, and advertise their own trades and services in these news journals. Advertisements highlighted the skilled labor of blacks in Austin, and subscribers promoted skilled trades such as barbers, blacksmiths, caterers, doctors, grocers, and shoemakers. Black Texas newspapers also contained advertisements for food, clothing, household items, medicine, legal advice, literary and newspaper subscriptions, and educational institutions. Patent medicines claiming to treat consumption, catarrh, blood diseases, and various female “complaints” represented a large percentage of the mass manufactured items advertised in the black newspapers. Influence on CommunitiesIt is probably not a coincidence that many of the medicine bottles found at the Williams farmstead are marked with the names of companies and products that were advertised in the black newspapers. This could indicate that some members of the Williams family were reading the black papers and responding to the advertisements. It may also mean that the black press influenced the local stores where the family shopped and that the black community was linked to a regional economic network of black-owned business and white enterprises that had a significant number of black customers. One good example is the Morley Brothers Drugstore on 6th Street in downtown Austin. The newspaper sample contained 29 separate advertisements for the drugstore or specific Morley products, thus leaving no doubt that the Morleys were catering to the black consumers. The archeological link is that at least seven broken glass bottles found at the Williams farmstead were embossed with the Morley Brothers’ name and logo. As largely urban enterprises, newspaper editors may have concentrated on products that reflected the lifestyles and experiences of their city readers. However, editors may have adhered to their agendas to impart educational and moral instruction to their subscribers with the selection of advertisers. Reverend Campbell’s Sunday School Herald and the Herald promoted only two tobacco products, Blackwell’s Bull Durham Smoking Tobacco and the Natural Leaf Tobacco of Meriwether and Company. There were no advertisements for alcohol except for the inadvertent ads for patent medicines that contained alcohol. Whether through advertisements, news reports, or editorials, Black newspapers wielded considerable influence in the central Texas African American community in the late 19th century. Research in these historic papers is one of the most primary means for understanding the context of the times and for considering how blacks depicted their own lives in their print media. These journals were concerned with education, moral instruction, racial progress and equality. Most importantly, they were found to play a significant role in shaping black thought and political and racial ideology. |

|