Smuggling Wax

"For the Mexicans it's smuggling, but for

us it's importing." Wax has always flowed across the

Rio Grande either because buyers on this side would pay more

than the Banco or because cash was more quickly accessible

from Texas buyers. It is illegal under Mexican law to smuggle

wax out of Mexico, but not illegal under United States statutes

to bring it into this country for marketing if it is declared

with customs. Heavily laden burros have brought wax into Texas

at various places, including Stillwell's Crossing, Reagan

Canyon, La Linda, Boquillas, San Vicente, Solis, Santa Elena,

Lajitas, El Mulato, Presidio, and Candelária. It is

estimated that as many as 1700 tons of wax have been smuggled

across the Texas border in some years.

One informant described participating in a nocturnal

wax-purchasing session near Big Bend National Park. He and

the purchaser went to a prearranged place and camped. Long

after dark a dry sotol plant flamed up on a hillside about

a mile away, and he was told that the pack train would arrive

soon. Some time later a single individual came warily into

their camp. Upon determining that everything was in order,

the "scout" went out and, accompanied by several

other men, brought in the pack train of burros loaded with

wax. The gunnysacks of wax were unloaded from the burros and

the bargaining began. Various sacks were opened and the quality

of the wax (the amount of trash and sand content) was examined.

The purchaser would occasionally find a rock in a bag and

discard it, but occasionally a rock was added by the seller

before a bag was retied. Eventually a price was agreed upon

and the bags were weighed. The wax makers were paid in cash

and got on their burros and left. The wax was loaded on a

truck and hauled to a refining place some miles away, where

it probably was mixed with wax produced on this side of the

border. Some buyers, however, do declare clandestine wax shipments

to U.S. Customs before refining.

One refiner described making a "big wax

deal" in the park many years ago. The Mexican producer

demanded cash in pesos for the load. The buyer was afraid

to carry the cash with him to the rendezvous, so he had about

$20,000 in pesos sewn into a burlap bag and flown to the site

in a light plane. After the large burro pack train was unloaded

and the price agreed on, the plane was signaled to drop the

cash bag. The plane circled twice and the bag was thrown out

a window. Sailing on a brisk wind, the bag landed in a rugged

rocky area, and the buyer spent several uneasy hours helping

some very unhappy wax makers search for the bag of pesos.

Of course, the Banco has long sought to curtail

wax smuggling across the river. It subsidizes cooperatives

and provides acid (a necessary ingredient in wax making) to

the wax makers on a quota system, expecting to get a specified

quantity of wax in return. Wax makers who want to sell in

the United States usually have to get acid from their American

buyers. The Banco also tries to pay higher prices than U.S.

buyers, but it may take one or two months for payment, and

few wax makers want to wait that long for their money.

During the mid-1960s, there was a quota of 100

to 150 kilograms (220 to 330 pounds) per year for each family

that made wax, and it was estimated that 20,000 Mexicans subsisted

on wax production. More recently an ejido, or cooperative,

near Ojinaga was reported as having a quota of 800 kilograms

(1764 pounds) per month and as selling the wax for about a

dollar per kilo to the Banco. The cooperative got considerably

less for any wax that was smuggled across the border. One

buyer said at times there were from dozens to hundreds of

Mexican federal officers along the border trying to curtail

the flow of wax. This was especially true from July 1947 to

August 1948 and again between December 1952 and September

1953 when the Mexican government banned all manufacture of

wax from candelilla because the plant had become endangered

from overexploitation. During these years wax shipments reportedly

came from as far as 150 miles to be smuggled across the river.

One dealer, who prefers to remain anonymous,

said he has traveled to Mexico many times to locate people

who live by smuggling wax into Texas. He has often bought

as much as 30,000 pounds of Mexican wax at one time, and the

people who transport it make about 10 cents per pound profit

for smuggling the wax across the river. He described the transactions

as follows:

They always insist on coming in the middle

of the night, and I've worked all night inspecting shipments

many times. In the bags of cerote you often find what are

called "highballs," which are balls of wet ashes

covered in wax, and also rocks coated with wax.

In earlier days smugglers would bring as many

as 100 burros across the river laden with $10,000 to $20,000

worth of wax. One crossing was on the "old Boquillas

trail" below the park. In more recent years wax was brought

to the border in trucks and taken across the river at fords.

The informant said most of his wax originates in a big production

area around Quatro Cienegas, but some is made along the Rio

Grande.

In the late 1970s, it was not uncommon for

buyers to keep $10,000 to $20,000 in cash handy to pay for

wax arriving from Mexico, and, even though the buyers had

guns, they didn't feel the wax smugglers were dangerous because

"they are not bad people." However, the informant

had heard of shoot-outs between the smugglers and Mexican

officers in which men on both sides were killed. More often,

bribes were paid to appropriate officials in advance. One

buyer is supposed to have made infamous wax deals in the 1950s

that included payment of new gas refrigerators for Mexican

officials.

Several times I sold her gas refrigerators

that you couldn't get in Mexico. One time I delivered a

box to her at a place called San Vicente, right on the river…soon

here came a team and a wagon and we unloaded the refrigerator

on that wagon and I asked her, "Where does this go?"

She says, "It goes to a Mexican army captain about

200 miles in the interior of Mexico." (Interview

with D. D. Thomas by Mavis Bryant, Alpine, 1977.)

During a visit to the San Vicente area in 1980,

we observed a pickup fording the river with two used refrigerators

in the back. Apparently the system still works.

The Buyers

In the past, a bag of wax might be brought across

the river at any time, so buyers had to be in convenient locations

with a pocketful of cash. For years buyers were situated at

all the river towns and crossings between Candelária

and Stillwell's Crossing. One of the famous buyers was Maggie

Smith, a Big Bend legend who ran a store near Langford's hot

springs for many years. In Farewell to Texas, W.O.

Douglas presents a colorful account of her business practices:

Maggie Smith's main profit was in the wax

that she bought from Mexicans and resold to American processors...

she bought large quantities, selling them to refiners in

Alpine and Marfa. Occasionally, the Mexican authorities

obtained the help of our customs people in policing the

border. There would be raids, and Maggie, hearing the sound

of approaching officials from the sensitive acoustical position

of her store, would hide any wax in the ladies' restroom—a

place that the border officials, being gentlemen, never

entered.

Two wax buyers for the J.E. Casner operation

were interviewed in 1976. Tom Ornelas had been buying wax

for about 25 years in the Presidio area. He had just delivered

a big load of cerote (unrefined wax) to the refinery

a few weeks before the interview and had a little more wax

on hand at the time. He said the Mexican wax makers "declared"

their wax and delivered it to him in Presidio. They dumped

the wax out of the bags on a floor for the buyer to inspect

its quality. He said, "You must pour it out of the bags

and inspect it in order to not pay 40 cents per pound for

rocks." The wax makers kept their own burlap bags and

took them back to Mexico for reuse. Ornelas had on hand a

good supply of sulphuric acid to dispense to the wax makers

who needed it for rough wax refining, and he paid cash for

the cerote and rebagged it for shipment to the refinery in

Alpine. When the wax business was doing better he was on the

refinery payroll, but at the time of this report he worked

on a commission.

Mrs. Walker, manager of the old General Store

at Candelária, bought all the wax she could get and

was paying 35 cents per pound in cash at the time of her interview

in 1976. In better days she paid as much as 60 cents per pound.

She usually paid for cerote in U.S. currency and tried to

avoid using pesos, although almost all the wax she bought

came from Mexico. She used to get big loads—as much as

500 or 1,000 pounds per shipment—but by the 1970s she

usually got only 30, 40, or 50 pounds at a time. "I can

always tell when there is going to be a wedding or a funeral

across the river, because people start bringing in a half

bag of wax to get some cash." A half bag of wax, about

50 pounds, would have been worth $17.50 at the 1976 price

of 35 cents per pound, and might have brought twice that amount

at 1980 prices.

Walker said most of the wax made in Mexico at

the time of her interview (late 1970s) went to "the bank."

The Banco paid more per kilo than she could pay per pound,

but people had to wait 30 to 60 days to get their money, so

they brought some to her for quick cash. Most of the wax makers

that she knew worked at other jobs like planting and harvesting

crops and made wax between those other jobs. Wax making is

considered to be good money, and men can make more at it than

at "ranching or working for wages."

In the old days, Walker said, all her wax was

delivered by burro, but now most comes over in pick-ups. She

provides the wax makers with bottles of acid in return for

the wax. She had delivered about 1,000 pounds of cerote to

the refinery a few weeks before the interview, but at the

time of our visit she had on hand only about 100 pounds.

An informant in Presidio said that Guillermo

Galindo, the mayor of Ojinaga, was an active wax buyer in

the San Carlos area for years and became rich in the wax business.

Another well-known buyer was Gustavo Garcia, who lived near

Ruidosa. The informant, who prefers to remain anonymous, also

related a story about a Mr. Kalmore, who owned a store in

downtown Presidio, which indicates that wax buying may at

times be a hazardous occupation:

One night, real late, he bought a shipment

of wax and paid cash, but apparently the smugglers wanted

more money from his safe. They cut up his ears but he refused

to open the safe, so they hit him on the head with a pipe

and killed him.

Ironically, with the high market price in the

late 1970s, some wax was beginning to be carried across the

Rio Grande to Mexico for the first time. A rancher who was

producing a considerable volume of wax reported that some

of the men filched cerote and took it over to Mexico to sell.

He said he would have to be in the wax camp every day to prevent

this type of chicanery.

Wax Dealers

One of the principal figures of the modern wax

industry in Texas is J.E. Casner of Alpine, Texas, who became

involved with wax in about 1940 and was still refining and

marketing it, at age 88, when he agreed to an extensive interview

in May 1976. Through the years Casner has aggressively pursued

the manufacturing, buying, refining, and marketing of wax

and the attempted massive cultivation and harvesting of candelilla.

His accomplishments gained him the popular title of "Candelilla

Wax King" of west Texas. Casner purchased wax shipments

in Big Bend National Park in the early days and maintained

purchasing agents for years in Lajitas, Presidio, and Candelaria.

In 1976 Casner said he shipped a large load

of refined wax to a company in London. In earlier years he

shipped wax to the northeast by rail, but it became too expensive,

so he began using trucks to haul the wax (40,000 pounds per

load) to Houston. From there it went by barge to New York

and New Jersey. Following that he sold mostly to a New Jersey

broker and understood that most of his wax is used by Wrigleys

and American Chicle as a principal ingredient in chewing gum.

In our 1976 interview, Casner talked freely

about candelilla, graciously introduced me to some of his

buyers, gave a tour of his refining plant in Alpine, and reluctantly

sold ten pounds of raw and refined wax, at the current market

price, for research purposes. He said he usually pays 40 cents

per pound for cerote in 100-pound burlap bags. He then refines

the wax by boiling it in dilute acid; during the refining

process there is a loss of about 10 to 12 percent of volume

because of moisture and sand removal. He has sold up to one

million pounds of wax in good years, but now (1976) he can

get only small quantities along the border. He blames this

on the Banco in Mexico, a competitor in Marathon, food stamps,

and the minimum wage law. In better times, his wax profits

paid for a new refining plant, building and all, in only three

months.

The only other big wax dealer in Texas during

the late 1970s was David Adams of Marathon and Stillwell Crossing.

After taking over the family wax business in 1962, he was

doing fairly well just making wax on his ranch and selling

it to Casner. Then the "markets got sticky" in the

east, Casner stopped buying, and Adams went to New York and

met the wax brokers himself. After returning to the ranch,

he experimented until he learned how to refine cerote into

pure wax.

Adams' profits on wax tripled when he started

marketing it himself. In good years he refined as much as

60,000 pounds of wax per month, some of which was coming in

from Mexico, and sold it directly to wax brokers in New York

who handle all types of wax. He also sold wax directly to

the "Beech-nut" chewing gum company for a while.

At the time of his interview in 1977, the wax business was

very slow, with little being produced or "imported"

from Mexico. He blamed this situation on the Mexican government

for controlling the price of wax by manipulating supplies

and dumping expensive wax at cheap prices. He felt that this

was done, at least in part, to crowd him and Casner out of

the business and that it seemed to be working.

During a second interview in 1980, Adams was

much more optimistic, and the wax industry was again booming

with the price at $1.50 per pound. He said he could profitably

ship the wax to the northeast by truck in reduced loads of

about 20,000 (rather than 40,000) pounds per load because

of the increased value. The shipping cost was about $2,000

per load. He had produced and bought as much as 80,000 pounds

of wax per month and had probably averaged 60,000 pounds per

month over a three-year period. Although much of this wax

had come out of Mexico, he had been unable to buy as much

imported wax because of the higher prices being paid there.

At the time of the interview, he had about 22 men working

on his ranch cooking candelilla. He said he and Casner have

been the only refiners and marketers of candelilla wax along

the Texas border in the past two decades (1960s and 1970s).

In recent years they have sold from 120,000 to 150,000 pounds

per month, with most of it going to five companies on the

east coast. When asked if a load of wax has ever been hijacked,

he responded, "You can't get rid of a load of candelilla

wax very easily." However, he added that everyone is

careful to buy, only from people they know, to be sure they

don't purchase hijacked wax.

|

Marketing diagram for candelilla

wax, based on late 1970s economy and regulations. Although

the picture has changed, due to recent trade agreements

between the U.S. and Mexico, it is still as complex

as when Tunnell compiled this chart. Graphic courtesy

Texas Historical Commission. Click to enlarge.

|

|

"They always insist on coming in the middle

of the night, and I've worked all night inspecting shipments

many times. In the bags of cerote you often find what

are called "highballs," which are balls of

wet ashes covered in wax, and also rocks coated with

wax."

-Anonymous wax dealer in the 1970s.

|

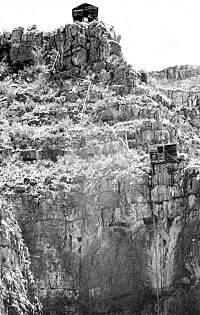

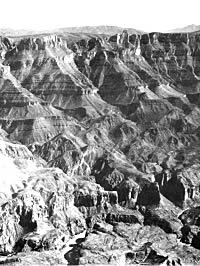

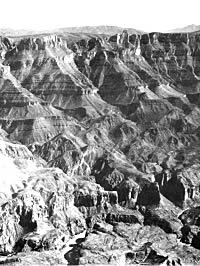

The rugged canyons of the Sierra

del Carmens support large stands of candelilla and were

the site of many wax camps. This photo at Boquillas

Canyon on the Rio Grande was taken by W.D. Smithers

from a small plane in 1936. Click to enlarge.

|

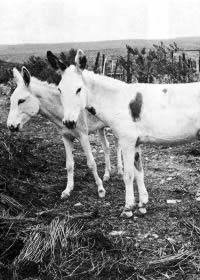

Sturdy burros saw heavy service as

pack animals during the era of the wax factories, as

they still do today. The animals hauled masses of carefully

packed candelilla from the canyon slopes to the factories

for processing. Photo by Glenn Evans, courtesy of the

Texas Memorial Museum.

|

|

"I can always tell when there is going to be

a wedding or a funeral across the river, because people

start bringing in a half bag of wax to get some cash."

-Candelária General Store operator Mrs. Walker,

1976.

|

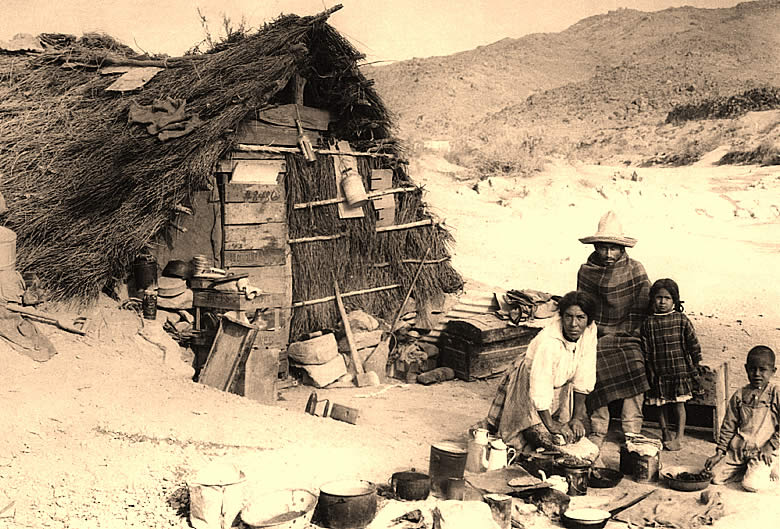

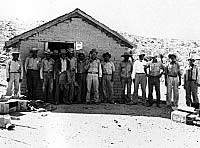

Workers brought furs, candelilla

wax, chino grass, and firewood to trade for necessities

such as sugar, flour, beans, and cloth at stores in

Glenn Springs and Castalon. Photo courtesy of Big Bend

National Park, NPS. Click to enlarge.

|

A red-blooming ocotillo plant adds

a touch of color to the grayish rocky slope. A stand

of candelilla is in forefront. Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

Click to enlarge.

|

|

"There would be raids; and Maggie, hearing

the sound of approaching officials from the sensitive

acoustical position of her store, would hide any wax

in the ladies' restroom-a place that the border officials,

being gentlemen, never entered.."

-William O. Douglas in "A Farewell to Texas,"

1967.

|

Bags of cerote, or raw wax. Photo

by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

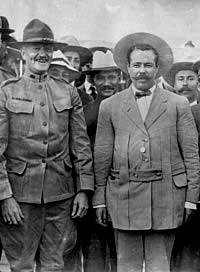

"Candelilla Wax King" J.E. Casner

in Candelária, Texas, 1976. The west Texas businessman

was still refining and marketing wax at the age of 88.

Photo by Curtis Tunnell, courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

|

When the "markets got sticky" in the east

in the 1960s, wax entrepreneur David Adams of Marathon

went to New York and met the wax brokers himself. His

profits on wax tripled when he started marketing it

himself.

|

Foothills and escarpment of Sierra

del Carmen, Mexico. Photo by Raymond Skiles. Click to

enlarge.

|

A candelilla plant in bloom. Photo

by JoAnn Pospisil. Click to enlarge.

|

|