Candelillera Maria Orozco (standing

in doorway) worked from age 10 alongside her father,

then worked with her husband. The family lived in brush

shelters called "jacalitas" or in caves in

the mountains while harvesting candelilla away from

home. Her children, Julia (seated), Veronica (red shirt),

and Chuy do not work with candelilla. Las Norias, Coahuila,

Mexico. Photo by JoAnn Pospisil. Click to enlarge.

|

The small town of Boquillas, nestled

at the foot of the Sierra del Carmens, was at one time

a critical port of entry. Today, due to NAFTA and security

measures, the border crossing has been closed and the

historic river ferry has ceased operations. Photo by

Susan Dial. Click to enlarge.

|

Candelária, Texas. Footbridge

over the Rio Grande to the village of San Antonio del

Bravo, Chihuahua, Mexico. The sign to the right warns

that it is illegal to enter the United States at this

point. This informal crossing was in use for thousands

of years before it was closed by the U.S. government

in 1996. Photo by JoAnn Pospisil. Click to enlarge.

|

|

The economic and cultural manifestations of the

candelilleros' proud traditions have withstood past

market assaults and, despite an uncertain future, the

candelilla wax industry remains an important economic

mainstay unique to the Big Bend region.

|

|

Curtis Tunnell visited some of the riverside

camps during initial survey and study of the candelilla wax

industry and observed in his 1981 report that "there

is a conspicuous absence of women." However, in subsequent

research, I have found that women often participated in the

industry, and these female candelilleras harvested

and processed candelilla alongside their fathers, grandfathers,

brothers and husbands. There is no stigma attached to female

participation although the form and extent varies according

to local custom.

Some candelillera tasks include harvesting,

handling the burros in camp and during candelilla transport,

cooking food for the crew, carrying water to fill the processing

vat, stomping the candelilla to pack it tightly in the vat,

skimming wax, and removing the spent plant from the vat and

stacking this yerba seca [literally, dried herb] away

from the processing area. Candelilleras generally are

strong-willed, stoic, and somewhat non-conformist with a love

of the outdoors. The likelihood of violent confrontations

with forestales probably accounts for the absence of

women in camps near the river.

Historically, field processed candelilla wax,

called cerote, was sold legally into the U. S. anywhere

along the Rio Grande to American buyers who generally paid

higher prices and in cash. The wax then was declared as soon

as possible at a formal port of entry. Both candelilleros

and U. S. buyers recount colorful incidents related to this

"direct" import across the Rio Grande which clashed

in mid-river with Mexican export restrictions that required

all wax to be sold through the Mexican National Bank.

In the 1990s the North American Free Trade Agreement

[NAFTA] eroded the independent production supported and encouraged

by the ejido system. NAFTA privatized the industry

which caused more centralization and increasing control by

large commercial interests. In 1996 all Class B informal Rio

Grande border crossings were closed by the U. S. government.

Candelilleros in northern Mexican villages like Manuel

Benavides [San Carlos], Boquillas, Jaboncillos and Las Norias

found their small profit margin could not support transporting

the wax to the relatively distant formal ports of entry at

Presidio and Del Rio [see map]. These imposed market conditions

forced the independent producers to sell their cerote to local

Mexican buyers.

The generally lax enforcement of the 1996 Class

B crossing closings ended following September 11, 2001. Presidio

and Del Rio then in reality became the only legal entry points

in the Big Bend region. This caused crucial tourist dollars

to vanish from the economies of border villages like Boquillas,

Santa Elena, and Paso Lajitas. Candelilla harvesting and wax

production escalated because the candellilla wax trade became

critical as the remaining legal means for participation in

a cash economy. Other alternatives for replacing lost tourist

dollars are not acceptable to most citizens. One option is

the costly special work permit for U. S. employment along

the border, perhaps in the expanding Lajitas resort. Another

more lucrative but illegal and dangerous choice is drug trafficking.

Today most cerote is sold to Mexican

buyers and warehoused in Mexico. Larger lots then are exported

to U. S. buyers/brokers through Presidio or Del Rio, or directly

to commercial consumers in the northeastern U. S., or to newly

developed markets in Germany and Japan. Current prices are

considerably higher than historically and often not competitive

for U. S. buyers. For the past three years, Mexican buyers

in the State of Chihuahua paid candelilleros 27 pesos [minus

3 pesos for social services] per kilogram, almost $6 per pound

at the exchange rate of 10 pesos per U. S. dollar.

With proper management, candelilla is a renewable

natural resource with myriad uses in our everyday lives [see

chart]. Candelilla's conservation and managed commercial exploitation

is becoming increasingly important as the population continues

to swell along the northern Mexican border, and survival in

this arid environment with its paucity of resources becomes

ever more tentative. The economic and cultural manifestations

of the candelilleros' proud traditions have withstood

past market assaults and, despite an uncertain future, the

candelilla wax industry remains an important economic mainstay

unique to the Big Bend region.

|

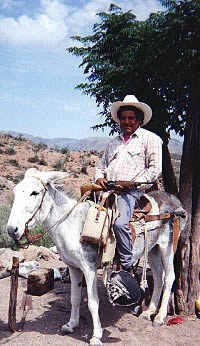

Candelillero Navidad Zubía

on his mule. This hardy animal remains the most reliable

form of transportation for hauling harvested candelilla

from steep terrain in remote mountain areas. San Carlos

Chihuahua, Mexico. Photo by JoAnn Pospisil. Click to

enlarge.

|

At age 13, candelillera Flora Zubía

Guevera began working candelilla with her father and

brothers. When they were working for another rancher,

the entire family sometimes camped out for three or

four nights while completing the job. Later she also

worked candelilla alongside her husband. Photo taken

near San Carlos, Chihuahua, Mexico, by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

Cool evening breezes are easier to

enjoy outdoors. The colorful and durable "cubre

de cama" (bed cover or quilt) is made from polyester.

One man insists that all the polyester pantsuits from

the 1960s and 1970s found their way to northern Mexico

where they provide bright, almost indestructible quilting

material. Jaboncillos, Coahuila, Mexico. Photo by JoAnn

Pospisil. Click to enlarge.

|

|