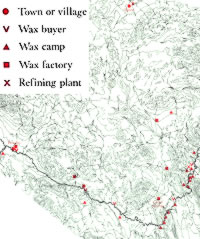

Primary concentration of candelilla

plants and wax production in west Texas and northern

Mexico at the time of surveys by Texas Historical Commission

(THC) archeologists. Click to enlarge.

|

A plume of smoke rises over the river

bank, alerting surveyors to the presence of a small

wax camp. Photo by Curtis Tunnell. Click to enlarge.

|

Burros bolt away from a wax maker

in a riverside camp piled high with cut candelilla.

Photo by Raymond Skiles. Click to enlarge.

|

|

The Chihuahuan Desert reaches its northern limit

in southern New Mexico, includes all of trans-Pecos Texas

except the Guadalupe Mountains, and extends southward through

the states of Chihuahua and Coahuila in Mexico. This vast

area is not noted for its economic productivity. Of course,

most areas serve very well for ranching, with sheep and goats

being more widely accommodated than cattle and horses. Small

amounts of silver, mercury, fluorspar, coal, sand, gravel,

and petroleum have been laboriously extracted in some sections.

Minor products include furs, honey, ornamental cactus, rope

fiber, rubber from guayule, hunting leases for deer and antelope,

tourism, and a modest amount of garden produce, corn, and

cotton from irrigated plots along the rivers.

Perhaps the most interesting and one of the

most economically profitable activities has been the extraction

of wax from the candelilla plant. Since the first decade of

this century, many millions of pounds of this high quality

wax have been removed from wild plants and marketed in dozens

of common products. Much of the wax production has been in

Mexico, but, over the years, varying quantities have been

refined and marketed along the international boundary in Texas.

Many people have subsisted along the Rio Grande by making

wax, and a few have grown rich through marketing.

The camps of the candelilla wax makers are one

of the most common types of cultural sites along the Rio Grande.

During an initial archeological reconnaissance through the

canyons in 1964 as part of a thousand-mile survey of the river

known as the "Cactus Cruise," we began to find and

record abandoned wax camps. Mounds of waste candelilla cascading

over the edge of a silt terrace often indicated site locations,

and these were recorded by means of sketches, notes, and photographs.

Along the river there were many stories about

burro trains of wax smuggled across and sold to representatives

of the big floor-wax companies. One day in the depths of a

canyon, a column of smoke led us to a wax camp in full operation,

and the fascinating story of a fugitive industry began to

be revealed. In intervening years numerous camps from different

decades have been recorded and many good people have consented

to interviews. The stories of candelilla wax and evidence

remaining in the camps have become a permanent part of the

heritage of the Chihuahuan Desert.

The wax camps are an interesting cultural phenomenon

for many reasons and one that might be studied from varying

points of view. The economic botanist, for example, might

view the wax camps as a specialized industry based on exploitation

of a single desert plant species. Historians see the wax industry

as a significant element in the opening of the last frontier.

The anthropologist and sociologist would find material for

study in the transient nature of the camps and the fact that

they are occupied by males only*, who live under primitive

conditions. The folklorist who is fluent in both Spanish and

English would no doubt find the camps a goldmine of information,

ranging from cures and costumes to tales of bandits and heroes

along the river.

For the archeologist, the wax camps are doubly

interesting, being an excellent source of cultural data and

insights in their own right and serving also as a veritable

experimental laboratory for generating and testing hypotheses

relating to prehistoric sites in the region, and the whole

is enhanced by the fact that active camps can be compared

to those that have been abandoned for various periods of time.

For all those who are concerned with the documentation

and preservation of cultural resources, all aspects of the

wax camps and those who live and work in them are significant.

The era of the candelilla camps may one day come to a close,

and it is important that this fascinating facet of our culture

be documented and studied in detail. We can learn valuable

cultural and environmental lessons by studying the camps.

Perhaps most important of all, from the cereros—the

wax makers—we can learn about hard work, productivity,

adaptation, ingenuity, persistence, pride, endurance, determination,

and survival against great odds.

*{Editor's Note: In the section entitled,

"The Industry Today,"

researcher and historian JoAnn Pospisil brings new information

to bear on what has long been considered a "male only"

industry.}

|

Looming canyon walls cast a shadow

over THC surveyors as they maneuver down a stretch of

the Rio Grande. During the archeological reconnaissance

tagged the "Cactus Cruise," surveyors began

to find and record abandoned wax camps. Photo courtesy

Texas Historical Commission. Click to enlarge.

|

|

We can learn valuable cultural and environmental

lessons by studying the camps. Perhaps most important

of all, from the cereros we can learn about hard work,

productivity, adaptation, ingenuity, persistence, pride,

endurance, determination, and survival against great

odds.

|

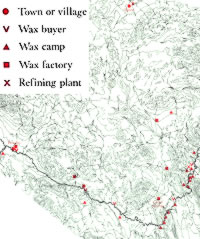

Locations of wax camp sites, factories,

and buyers at the time of the 1960s survey of the Rio

Grande canyons. Map courtesy of Texas Historical Commission.

Click to enlarge.

|

|