This wall post (just to the left

of the striped photo stick) burned into the ground,

but the charring did not continue all the way. The pointed

soil discoloration below the charred section shows the

shape and extent of the original sharpened post. Photo

by Doug Boyd

Click images to enlarge

|

Stunted juniper growing near top

of caprock overlooking Canadian Breaks near Hank's house.

Juniper was the favored tree for house posts, probably

because it was one of the few types of wood available

and it lasts longer before rotting than cottonwood and

other available trees in the area. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

|

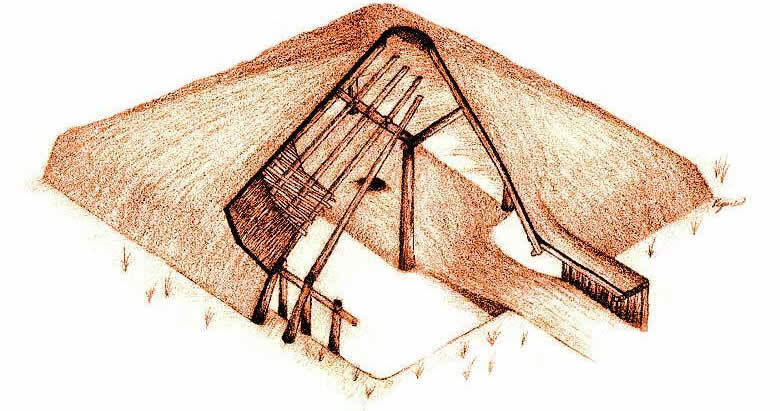

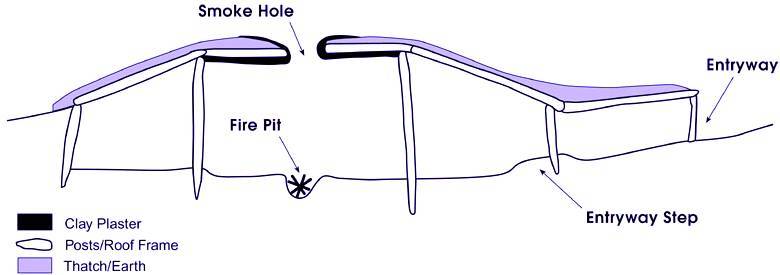

Once the preserved half of Hank's house was

excavated, we began trying to reconstruct how the whole house

might have looked. Although, of course, we will never know

for certain what the missing half of the house looked like,

many prehistoric Plains Village houses have been excavated

in the Texas Panhandle and the Southern Plains. Almost all

the houses that look similar to Hank's house are very symmetrical.

Thus, we assume that the north half was a mirror image of

the south half. Granted this assumption and the preserved

facts, the full house was rectangular with its long axis oriented

east-west and its entrance facing east. The dimensions (length

x width) and interior floor space of the house were 6 meters

(19 feet, 8 inches) east-west by 5.6 meters (18 feet, 4 inches)

and had a total area of 33.6 square meters (362 square feet).

Accurate measurements of the depths of all postholes

(from the house floor level) were made, and accurate measurements

of the maximum post diameters were made for all of the charred

posts. When no charred wood was found, it was still possible

to estimate the approximate width or diameter of the post

based on a comparison with the charred posts on the west wall.

Because the postholes along the south and east walls were

approximately the same diameters and depths as those on the

west wall, it is fair to assume that the posts in these holes

were in the same size range too. When the sizes and depths

of all of the posts and postholes are compared, it reveals

some interesting things about how Hank's house was built.

(See Post

Dimension Table).

It is safe to assume that the posts that were

structurally most important were larger and set deeper in

the ground because they had to hold up the most weight. As

might be expected, then, the two central posts that held up

the main central frame in the center of the house were much

larger (diameter = 15 centimeters or 6 inches) than all of

the other posts and were set deeply in the ground (average

depth = 57 centimeters or 22.5 inches). In contrast, the posts

along the walls were smaller (average diameter = 8.75 centimeters

or 3.6 inches), more variable in size, and were all set less

that 43 centimeters (17 inches) into the ground.

Careful excavation of the charred posts and

postholes along the west wall, along with detailed observations,

led to another conclusion about house construction. All six

of the posts that were set into postholes below the floor

level were leaning inward toward the center of the house.

Measurements of the angles of the charred posts and postholes

revealed that all of the posts were leaning slightly eastward

ranging from 11.5 to 17.5 degrees off of vertical. When all

of the angles were averaged, it shows that the west wall of

the house leaned inward about 14 degrees.

|

Notice the slight incline of the

outline of the posthole of this wall post. The wall

posts were purposefully set angled out to help support

the roof. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

|