Artistic Expression

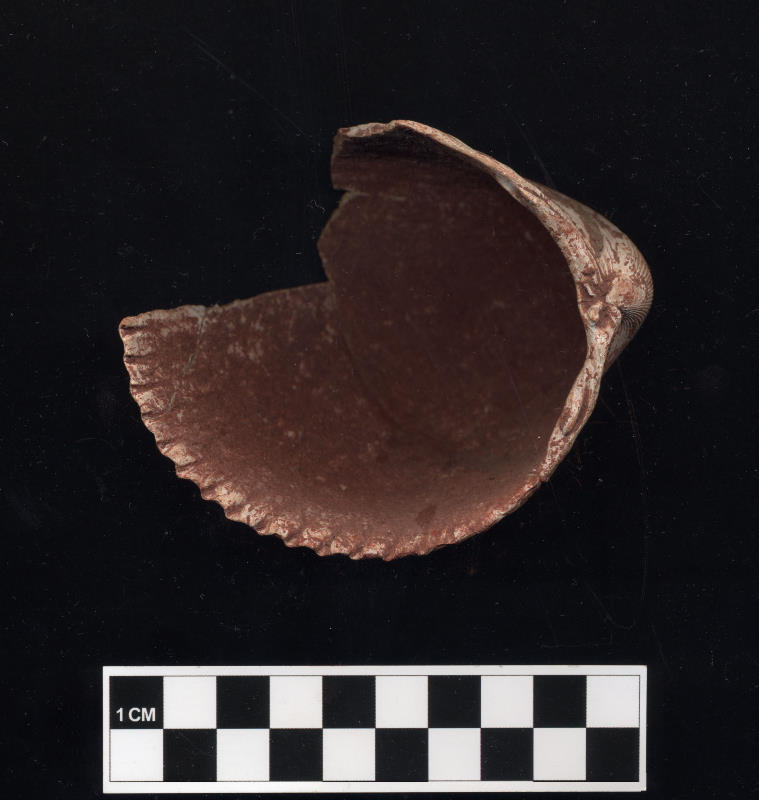

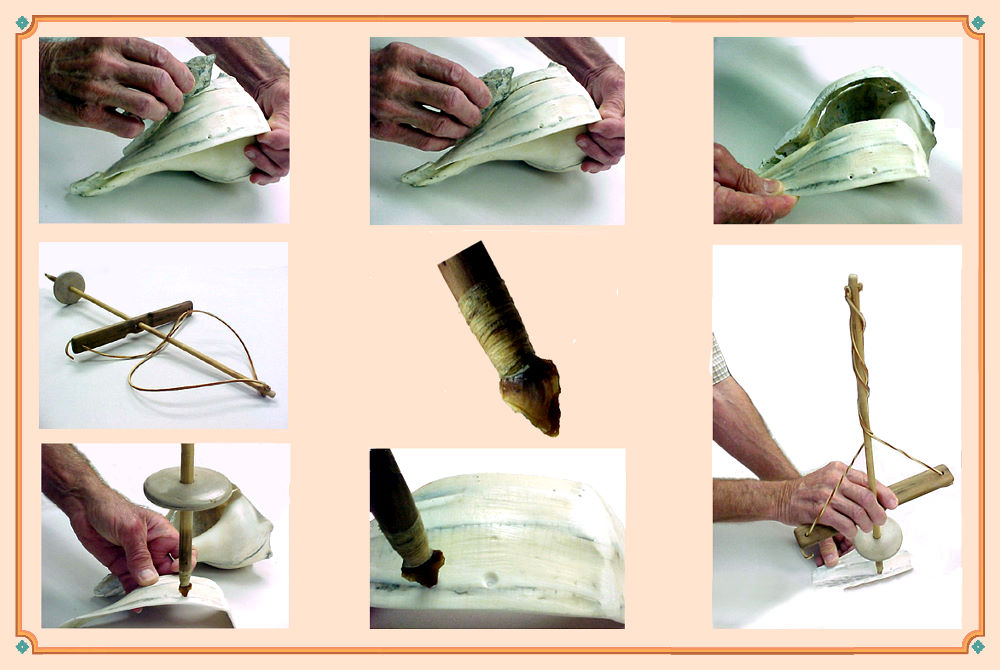

The coastal prairies and marshlands region of Texas retains only traces of the rich artistic endeavors of its native peoples, tantalizing reminders of the creativity, imagination, and traditions prevailing over thousands of years. Unlike the Trans-Pecos and Lower Pecos regions, where massive canyon walls served as canvasses for paintings in the past, the Texas coastal region had no comparable medium for expression. A variety of natural resources, however, enabled fine artistry on a smaller scale. The region's artistic wealth is primarily shell ornaments, bone artifacts, and clay pottery. Using simple tools and innovative technologies, native artisans transformed marine and freshwater shells and animal bones into intricate ornaments and ritual objects, and clays and natural pigments into pottery vessels and body paints. Although less abundant in this region, chert, sandstone, and quartz materials were sometimes chipped, pecked, or carved into items clearly intended for ritual purposes. Another form of artistry—the elaborately tattooed and painted bodies of native peoples of the region—is often mentioned in the journals of 17th- and 18th-century Europeans. Coastal artists used a variety of designs and motifs in their crafts. Although some were merely aesthetically pleasing; others carried important symbolic messages. Given the region's location, some of the iconography may have been influenced by cultures in nearby regions: especially those of the Lower Mississippi Valley and southern Louisiana to the northeast. These diverse expressions of the region's artisans reflect cultural and religious traditions of their time. Lacking written records and living traditions, almost all of the precise meanings have been lost. It is apparent, however, that the production of art and ritual items played an integral role in the lives of the native peoples of the coastal prairies and marshlands. Numerous ornaments and decorated objects have been recovered from archeological sites along the Texas coast. These "portable art" objects—necklaces, musical instruments, pottery, and other items—likely were carried from camp to camp and sometimes traded or exchanged over long distances. Other objects, including some of the most intricately designed and unusual, were placed in graves of the dead in coastal cemeteries. These offerings indicate the importance of artistic and symbolic expression in coastal funerary rituals. Shell ArtifactsWorked shell is the hallmark artistic expression of the coastal prairies and marshlands. The estuaries, river deltas, bays and beaches provided a diverse array of shell for the natives to utilize. The sparkling interior of the freshwater mussel and radial symmetry of the lightning whelk caught the eye of the coastal natives. Leaving aside the use of shell for toolmaking (see Marine Shell Tools), shells were also made into necklaces, "tinklers," and gorgets. Shellfish are found in various contexts along the Texas coast and range in size from the large lightning whelk (Busycon perversum pulleyi), to the diminutive minute dwarf olive (Olivella minuta). Throughout North America, many native peoples associated shells with death, fertility, and rebirth; therefore, it is not surprising that most artistically modified shells have been found in funerary contexts. (See Marine Shell Ornaments, Icons and Offerings to learn more and see other examples.) To judge by quantity, quality, and diversity of form, native artisans favored one shell over all others from the Texas coast: the lightning whelk. This rather large carnivorous gastropod, unlike almost all others, is sinistrally spiraled (counterclockwise, to the left), a peculiar geometry that is said to have given the shell special symbolic importance. Ornaments made from these shells are found are in both prehistoric and historic contexts along the length of the Texas coast as well as in sites hundreds of miles inland, indicating their importance in trade. Whelk shell was used to make disk beads, tubular beads, "danglers," pendants, and gorgets Avocational archeologist Bill Birmingham of Victoria has reconstructed the technique of making a whelk pendant similar to the ones found at the Early Archaic Buckeye Knoll site on the central Texas coastal plain. Using simple tools—a bifacial stone knife and wood and leather pump drill equipped with a chipped-stone tip—Birmingham used a groove and snap technique to create and decorate nearly identical pendants with patterns of lightly drilled impressions. He arrived at this technique through several experiments: using an alternate tool—a sandstone abrader—took nearly twice as long to cut a groove in the shell. |

|

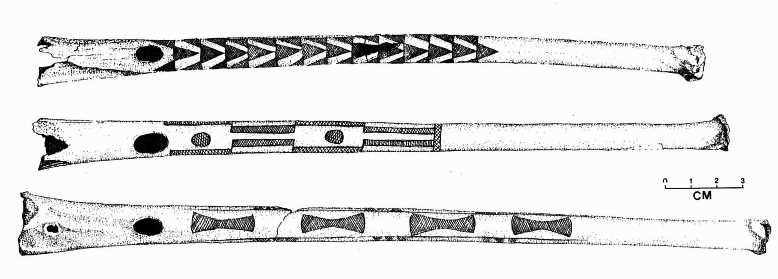

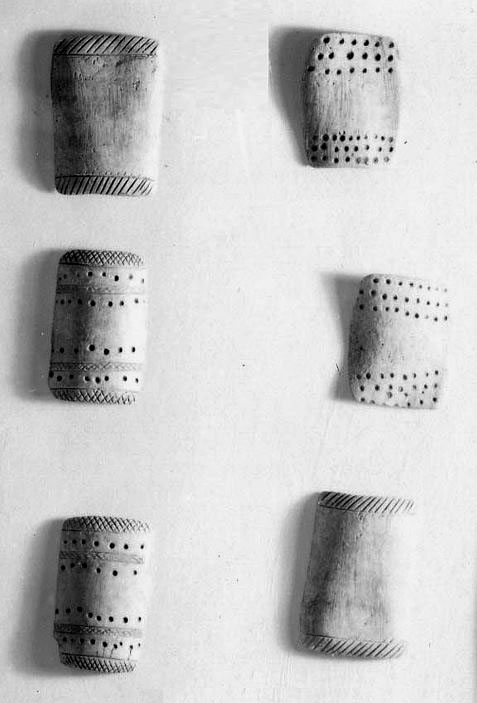

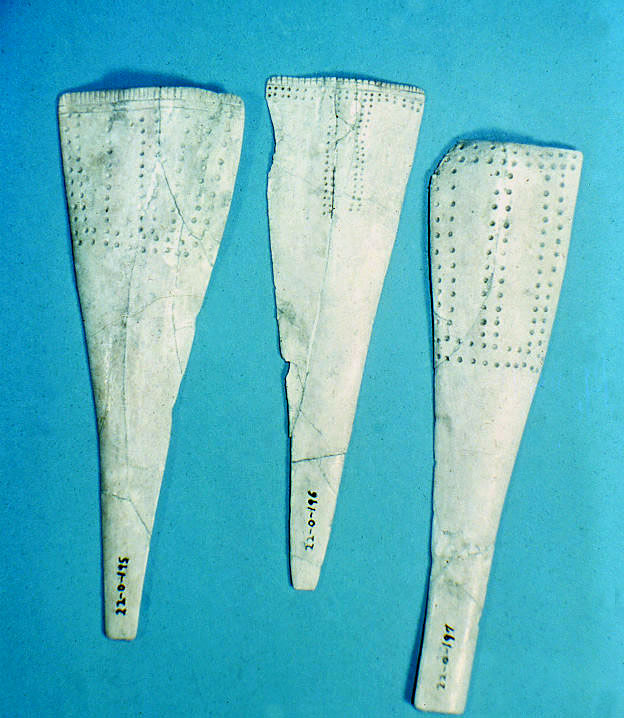

The central spire, or columella, of the whelk was also used to make ornaments. The coiled, elongate structure of the spires made for interesting hair ornaments; they also could be drilled lengthwise into long beads and strung into necklaces or "dangled" from a drilled hole through one end of the columella. Several graves at Mitchell Ridge contain whelk columella beads. These ornaments may be indicators of status or wealth, thus it is interesting to note that at that site whelk beads are found primarily in the graves of adult males and children. Decorated BonesBone was another important artistic medium utilized by the natives of the Texas coast. Some of the most skillful craftsmanship is found on bone artifacts made from a diverse range of animals. The bones of bison, deer, whooping cranes, and even humans were carved into ornaments, ritual objects, and musical instruments in prehistoric and historic times. An unusual example of artistry comes from several graves at Mitchell Ridge. Delicate bird-bone whistles were made from whooping crane ulnas (wing or forelimb bones). Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric flutes were engraved with a variety of geometric patterns. Chevrons, hour-glasses, and rectangular designs are found mid-shaft on these ornate instruments. These unusual grave offerings are only known from the Galveston Bay area and farther north and east in southern Louisiana and southeast Texas. |

|

|

|

|

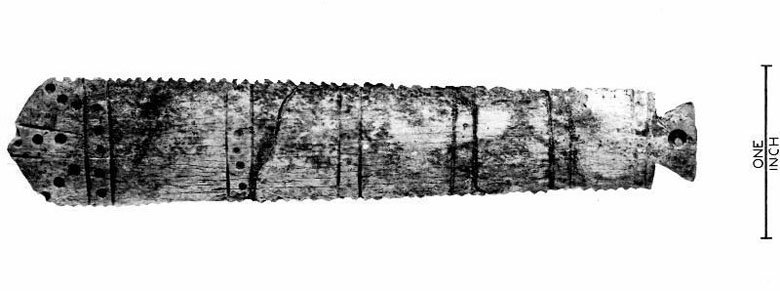

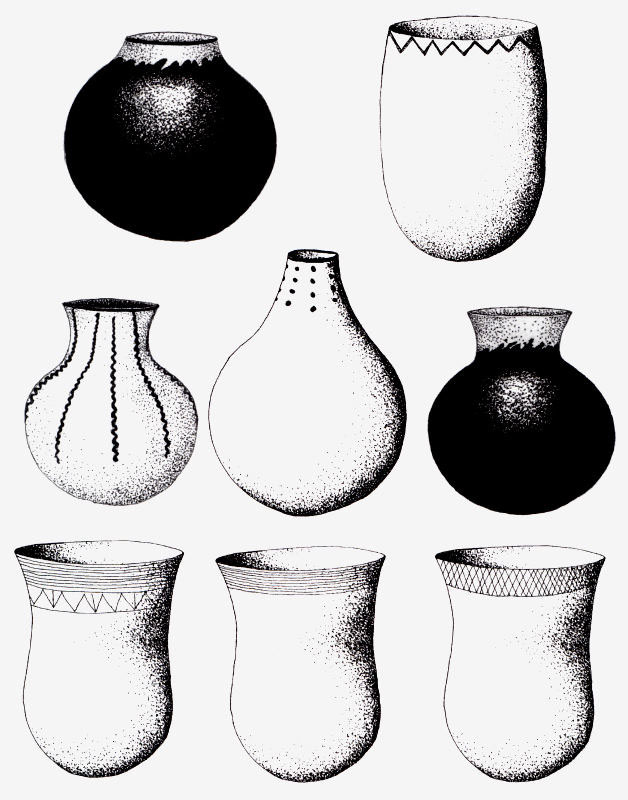

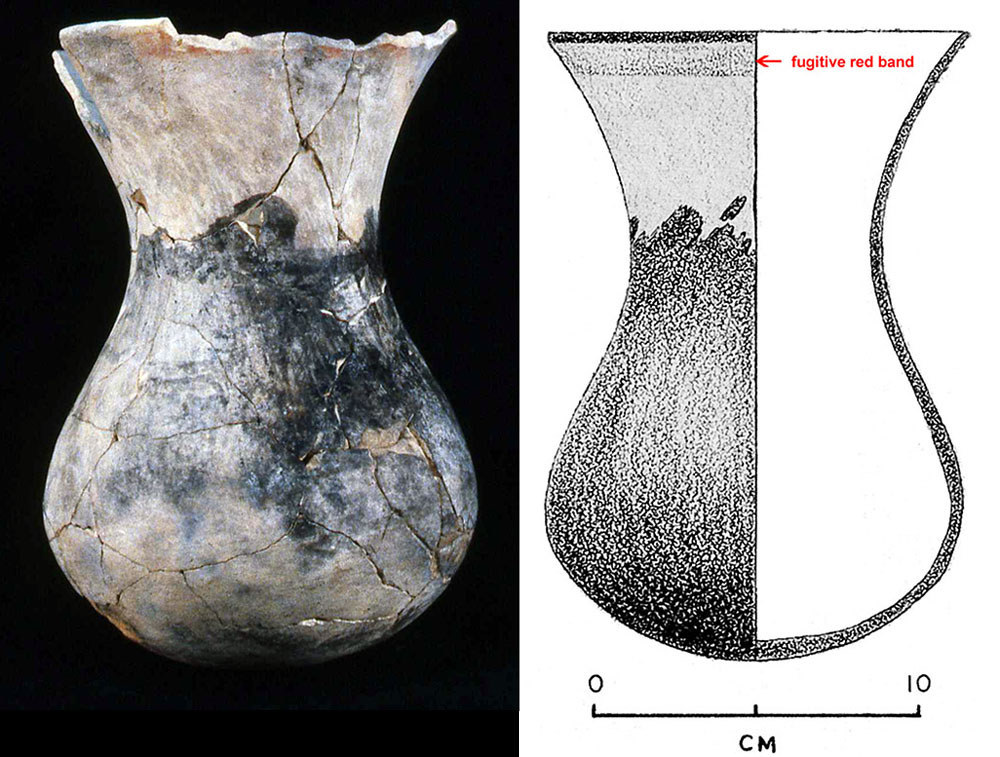

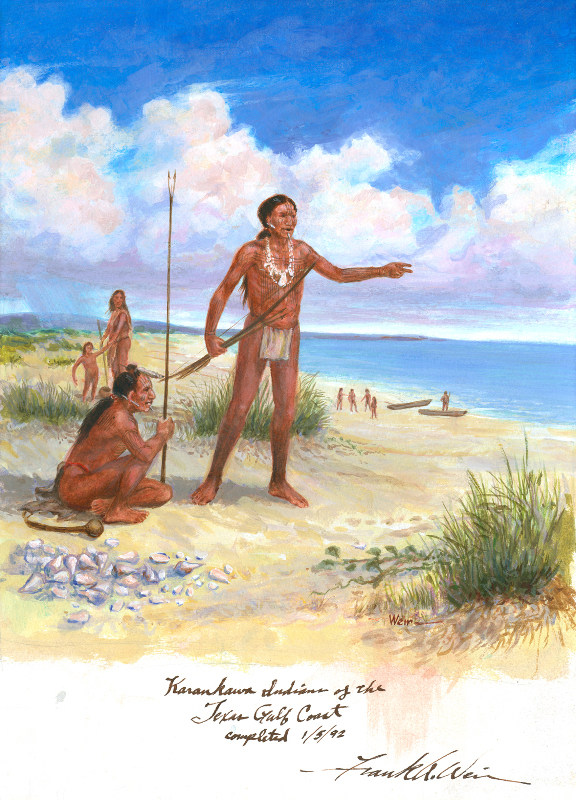

A small bone ornament from the burial of a woman at Caplen Mound cemetery site (41GV1) was carved into an elongate shape resembling a feather. The piece has incised horizontal bars bracketing a series of punctuations as well as carefully serrated edges. Because it was found near the skull, investigators speculated that it may have been a hair ornament. Another interesting Caplen Mound grave offering was a decorated turtle carapace laid in the burial of an infant. Drill holes in the shape of a "U" suggest the carapace served as a breast plate or rattle. As a rattle, the carapace may have been used in shamanic rituals. Achieving a trance state through repetitive music, which typically involved rattles and chanting, often accompanied shamanic ceremonies. Thus, decorated bone grave goods probably served a function in this life and the next. Other activities are represented in three pairs of bone gaming pieces incised with crosshatched triangles recovered from a prehistoric grave at the Harris County Boys School site. Besides sport, gaming pieces may also have been used as divining tools by shamans to interpret messages from the gods. The oracular nature of these gaming pieces is enhanced by the choice of bone as a medium. PotteryIdeological motifs are dynamic expressions, changing with time and cultural contact. Ceramics provided native artists another medium for expression. On the upper Texas coast, Tchefuncte pottery, with cultural ties to the southeastern United States, appeared in the area as early as 400-500 B.C., followed by the Goose Creek and San Jacinto series in the early centuries A.D. On the central Texas coast, Late Prehistoric groups ancestral to the Karankawa produced a distinctive pottery termed by archeologists as Rockport ware. The Karankawa continued producing vessels of this type into Historic times. Goose Creek and San Jacinto ceramics are found mainly north of Matagorda Bay and appear to have common motifs with Lower Mississippi Valley and southern Louisiana ceramics. The artist either used a rocker stamp or a fine incising tool to decorate the ceramic with culturally important motifs. Stamped ceramics date as early as A.D. 100, while incised ceramics date as early as A.D. 750. For example, ceramic sherds recovered from Mitchell Ridge have horizontal, vertical, and cross-hatched lines below the rim as do sherds recovered the Lower Mississippi Valley and southern Louisiana. These shared motifs suggest these two cultures were in close contact. Perhaps the common motifs express commonalities in cosmological and religious views. The peoples of the central Texas coast produced a diverse array of ceramic forms, including narrow-mouthed ollas, wide-mouthed jars, and bowls. These Rockport ceramics were usually made from a sandy paste clay body and often decorated with black paint made from asphaltum, a naturally occurring tar produced from petroleum leaks in the Gulf of Mexico. Motifs were either incised or painted near the rim of the vessel. Vessels treated with asphaltum and/or painted are called Rockport Black-on-Gray. These vessels have a grey slip and are painted with black asphaltum. Vessels with incised motifs are known as Rockport Incised. The two most dominant motifs are the horizontal line and chevron, which was sometimes cross-hatched. One unusual Rockport Polychrome vessel was reconstructed from the Kirchmeyer site in Nueces County. It has red ochre and black asphaltum pain over a white slip. A wide variety of Rockport pottery motifs has been identified by archeologist Richard Weinstein based on the large collection of sherds recovered from the Guadalupe Bay site, a Karankawa campsite visited over hundreds of years. A gallery of Rockport pottery is provided in the TBH Guadalupe Bay exhibit.

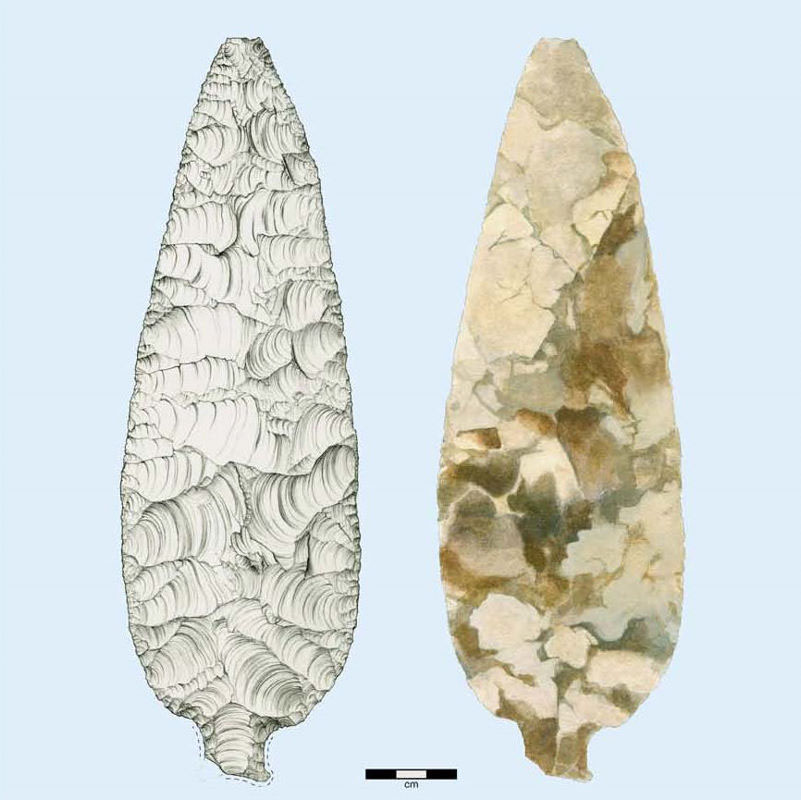

Artistry in Stone |

|

Quartzite and limestone grooved stones from the central coastal plain on display at the Museum of the Coastal Bend in Victoria. |

In part because stone resources are limited in the coastal prairies and marshes, stone was an infrequently used medium for artistic expression. Nonetheless, there are a number of stone artifacts attesting to the range and skill of native craftsmen including gorgets, ceremonial knives, and pipes. Perhaps the most stunning example is a unique ceremonial knife from an Early Archaic grave at Buckeye Knoll. Not only was it made by a master craftsman from a previously unseen variegated chert, but its fluted and edge-ground stem resembles early "fish-tail" Paleoindian projectile points known from Central America. How and when this unique item found its way to the lower Guadalupe valley on the central Texas coast is unknown. Robert Ricklis believes that "Big Fish" likely served as a symbol of authority and that it was an heirloom piece passed down through many generations. Thus, this precious grave good marked the elevated status of the interred. The Buckeye Knoll cemetery also has examples of a rather elaborate ground stone industry that includes bannerstones, perforated plummets and elegantly shaped and polished quartzite grooved stones. The bannerstones and plummets are thought to reflect extensive interaction with cultures of the Southeastern U.S., where similar objects occur. The grooved quartzite (and sometimes hard limestone) stone artifacts are more common in the central coastal plain, suggesting local manufacture. Similar to whelk shells, stone was also worked into gorgets. A slate gorget found in Kleberg County has three suspension holes. Since slate is a non-local material, this gorget was probably traded in from northern Mexico. Other artistry is seen in carefully shaped and faceted quartzite plummets, some of which have been in grave contexts. Body ArtTattoos and body paint are another facet of artistic, cultural, and ritual expression. Body ornamentation such as hair styles and piercings also fall under the category of body art. Most of our information concerning body art comes from 17th- and 18th-century accounts of European travelers and priests passing though the area. While the exact function of body art and ornamentation is still unclear, certain markings were probably used to align the person with a specific clan, ethnicity, or social rank. In other cases, body markings were applied before going into battle or performing a specific ritual. According to several accounts, tattoos and body paint were commonplace among the coastal natives. The Spaniards called the natives of the Rio Grande delta Borrados—which loosely translates to "those smeared with ink"—because of the predominance of body paint and tattoos. In this region men tattooed their face, while women tattooed their face and body. According to Gatschet's 1891 study, the Karankawa had face markings consisting of "a small circle of blue tattoo over either cheek, one horizontal line extending from the outer angle of the eye toward the ear, and three perpendicular parallel lines on the chin." Gatschet notes that Karankawa boys were tattooed in their tenth year as a rite of passage. For the natives of the Prairies and Marshlands, the body was a canvas adorned with a variety of artistic expressions. Artistic Expression was written by Barry Kidder, graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at Texas State University. SourcesAten, Lawrence, E. Gatschet, A.S. Ricklis, Robert A. 2004 The Archaeology of the Native American Occupation of Southeast Texas. In The Prehistory of Texas , edited by Timothy K. Perttula, pp. 181-202. Texas A&M University Press. 2004 Prehistoric Occupation of the Central and Lower Texas Coast: A Regional Overview. In The Prehistory of Texas, edited by Timothy K. Perttula, pp. 155-180. Texas A&M University Press. Salinas, Martín Weinstein, Richard A. |

|