Marine Shell Ornaments, Icons and Offerings

Along the Texas coast marine and freshwater shell were used prehistorically as body adornment, as status icons, and for burial with the dead. These ritual usages were not necessarily restricted to coastal life-ways, however. Archaeologists have found artifacts of prized mollusks from the Gulf of Mexico far inland in a variety of contexts—from large Archaic period cemeteries located many miles from the shore, to dry caves in Mexico. As a desirable trade items, shells were traded along routes that stretched as far north as Canada, or south to Mesoamerica.

The habit of wearing seashells, but also burying them with the dead (and therefore restricting the supply of them) has a long history in Texas and elsewhere, spanning thousands of years and many different cultures. This pervasive pattern suggests that marine shells, as well as those of freshwater mussels, were not only coveted for their beauty, but also imbued with economic and spiritual significance. Shells symbolize water, creation, fertility, death and rebirth, and their use in ritual contexts was a fairly universal occurrence, especially as part of mortuary customs. Early inhabitants of the New World may have believed that placement of shell with the dead would allow the deceased access into the spirit world.

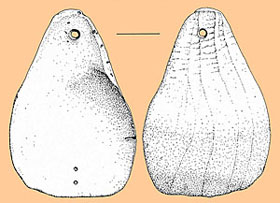

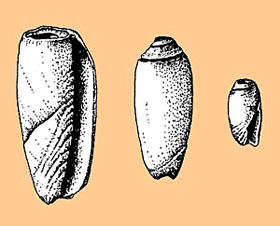

Three species of shells found along the Texas coast were commonly fashioned into jewelry or ritual accessories, and traded widely in prehistoric times: Lightning Whelk (Busycon Perversum), Lettered Olive (Oliva sayana) and Minute Dwarf Olive (Olivella minuta). Larger gastropod species like Florida Horse Conch (Pleuroploca gigantia) and the True Tulip Shell (Fasciolaria tulipa), as well as other cone and bivalve species, were also utilized, but not as extensively. The most diverse range of shell species used to make artifacts occurs n the Rio Grande delta area at the southern tip of Texas and northeastern Tamaulipas. Although much less common than marine shell, delicate freshwater mussel shells, from river and estuarine environments, were fashioned locally all along the Texas coast into decorative items frequently found with burials.

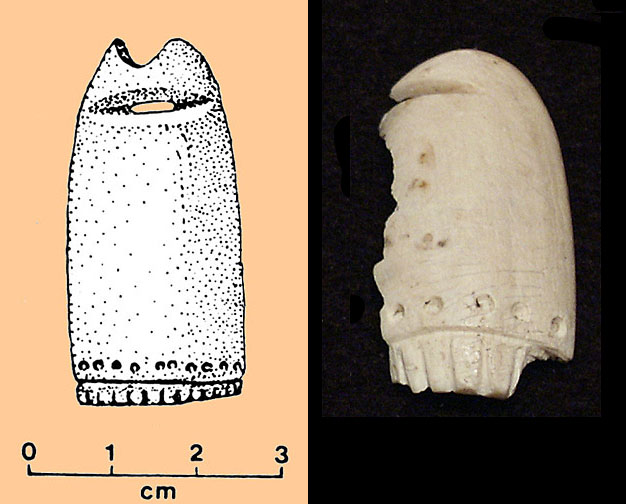

From these shell types came an array of ornamental and ritual pieces, some remarkably beautiful: pendants, gorgets, earrings, hair ornaments, beads for necklaces and bracelets, “tinklers”, musical parts, clothing accessories, and engraved shell cups associated with grave offerings.

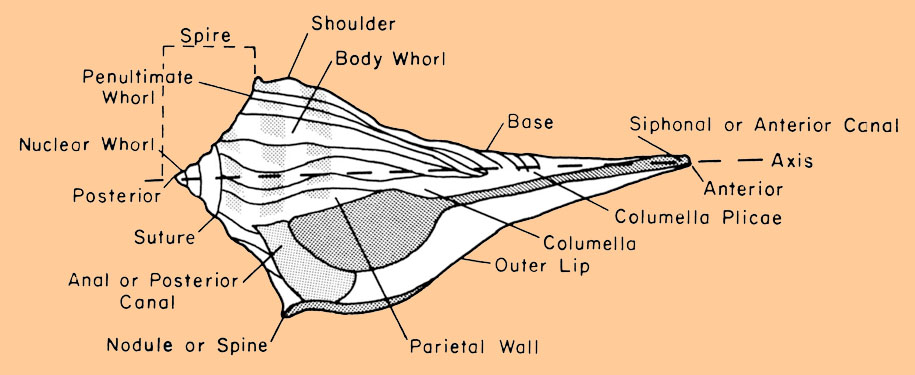

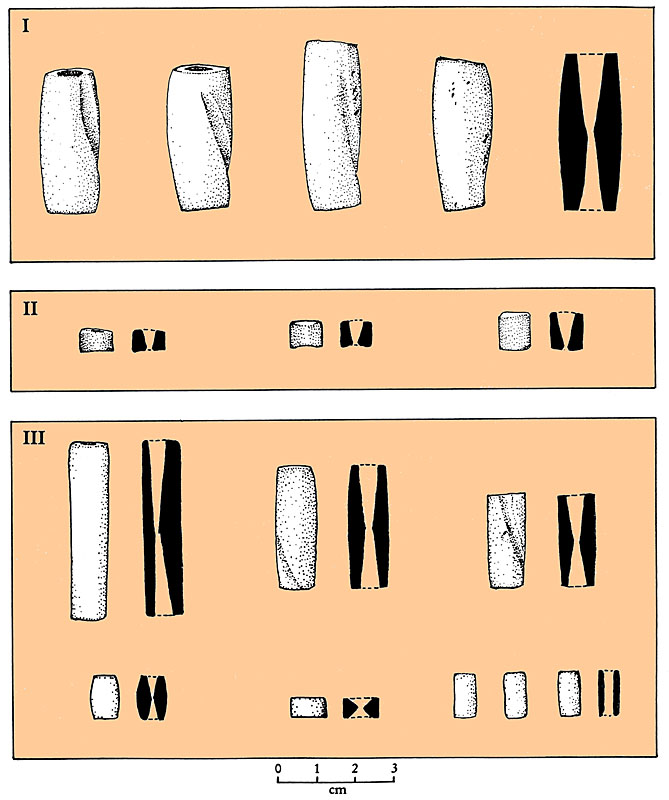

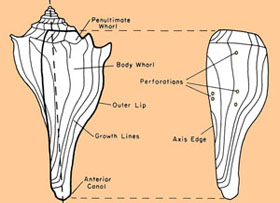

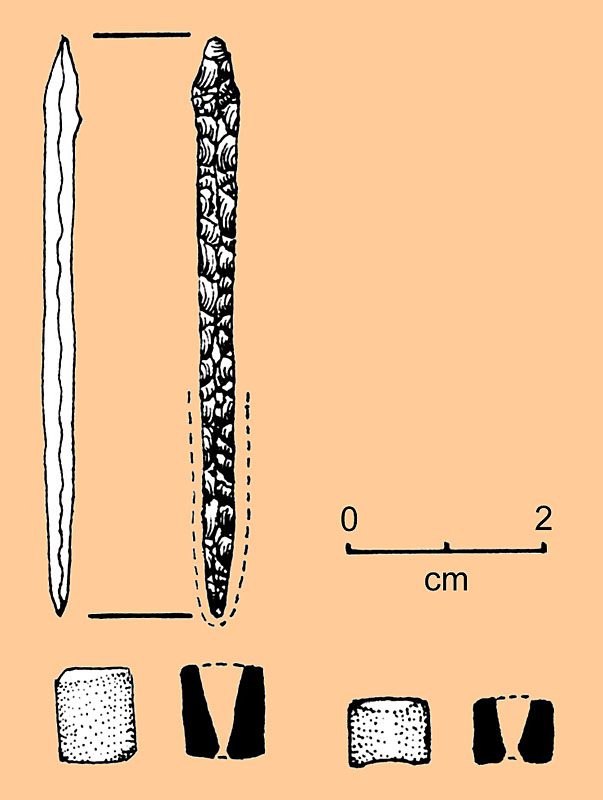

Whelk Pendants and Gorgets: The lightening whelk ranges in size from 6-12 inches in length, and is sinistrally spiraled (to the left). An assortment of pendant and gorget forms, made from the shell’s detached and edge-ground whorls, were often pierced for suspension, or sewn onto clothing. Those found in graves were usually positioned near the neck or chest of the interred individual, presumably hung by some sort of natural fiber. Pendants manufactured from whorl segments that include portions of the anterior canal and penultimate suture can be quite large and elongated, incorporating traces of the natural sinistral spiral. Smaller pendant types vary in shape and size but are sub-rectangular or sub-triangular with occasional incised surface decoration or punctuations, and multiple, biconical perforations drilled along the long axis or apex of the piece.

|