Marine Shell Tools

Along the Texas coast where access to raw materials for stone working was relatively scare, enterprising aboriginals made tools out of the toughest material at hand—marine shell. Implements manufactured from shell were used for a wide variety of kitchen tasks, animal and plant processing, and woodworking. The more durable species of whelk and sturdy clam shells were adaptable to precise modification while others, may have been picked up, sharpened, and used on the spot for expedient cutting and scraping tasks and then discarded.

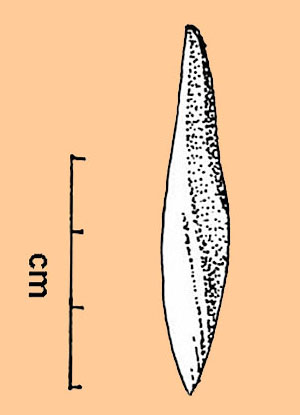

Lightning whelk (Busycon perversum), common rangia (Rangia cuneata), sunray venus (Macrocallista nimbosa), and oyster (Crassostrea virginica) were the species most commonly worked. These, and occasionally a few other species of bivalves and gastropods, were fashioned into many essential tools: scrapers, knives, projectile points, net weights, gouges, adzes, hoes, vessels, scoops, containers, fish hooks, barbs, and weaving tools. The use of marine shells along the Texas coast is part of a much broader widespread pattern along the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

In Texas the geographic range of different species plays a role in the types of tools found in archaeological contexts. For example, in the warmer waters of south Texas, sunray venus bivalves and the robust whelk columella tools (made from the sturdy, central column after the outer whorl has been removed) are more prevalent than on the Upper Texas coast. In general, there is a north-south gradient of increasing salinity along the Texas coast, due to dryer climate to the south which results in less freshwater inflows into coastal bay/estuarine systems. Because of this, low to moderate salinity oysters predominate to the north, while higher salinity bivalves and gastropods are more abundant toward Corpus Christi Bay. In the central and upper coast, rangia are found clustered in dense beds in the brackish water of the marshland estuarine zones along the lower stretches of rivers and streams entering bays.

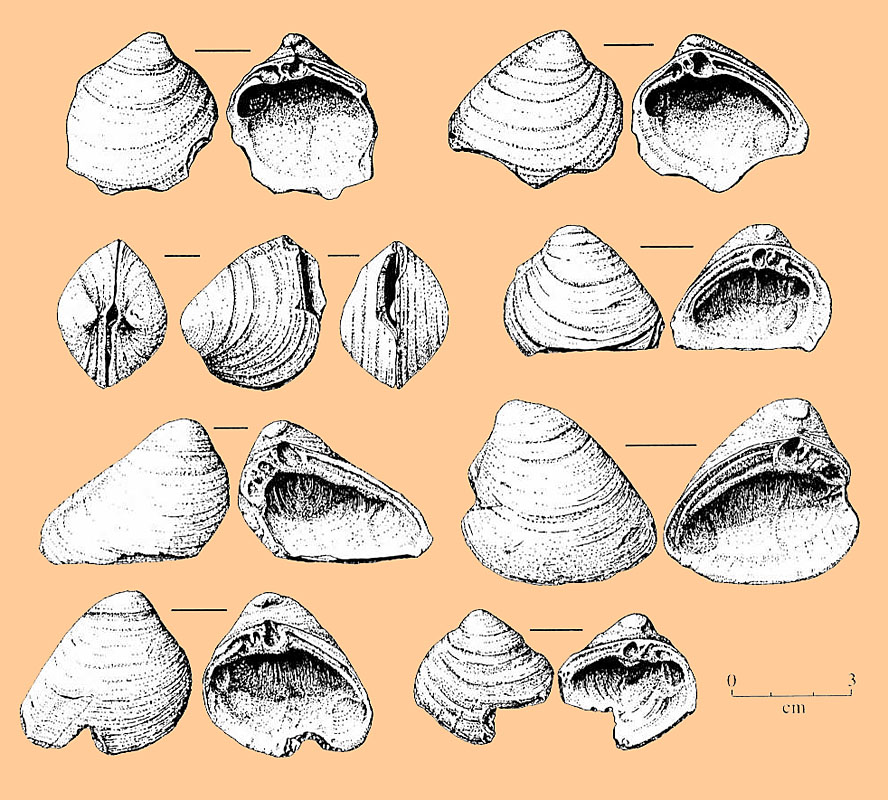

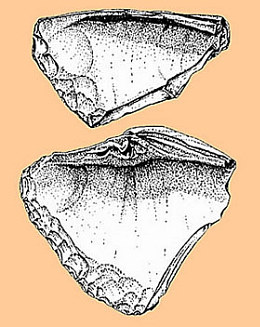

Common Rangia: Alteration patterns seen on Rangia cuneata bivalves may be attributable to direct or indirect human activity. Some valves may have been used as is as expedient fish scalers, while others that show patterns of nicks, notches and cut marks on their margins probably resulted from human shucking activity, or simply from natural breakage in the shell midden. Because these brackish-water clams were major food resources and most easily opened by briefly heating them in small fires (hearths), many rangia shells have been burned, which weakens the shell. Another reason rangia are often found in relatively poor condition is because discarded rangia shells are found in dense accumulations (shell middens) that were no doubt tromped on and deteriorated as the exposed shell deposits weathered.

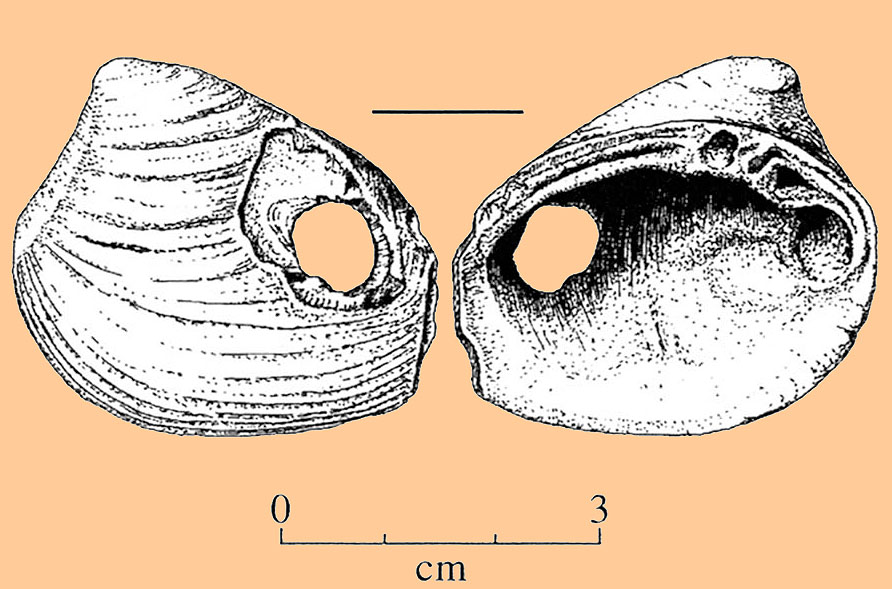

Thus it is not surprising that patterns of natural and intentional modification are sometimes hard to distinguish. This is especially true for perforated valves because the holes can result from either natural predation, or from human alteration. Of the perforated rangia found at the Guadalupe Bay site on the central coast, only the larger sized valves had holes consistently located on the upper posterior portion of the shell body. Whether or not the holes were intentionally or naturally drilled may not really matter because these perforations provided fisherman or hunters an easy way to use the shells for net weights or bolo weight. Also, the holes allowed the bivalves to be tied together with cordage for a variety of functional and ritual uses.

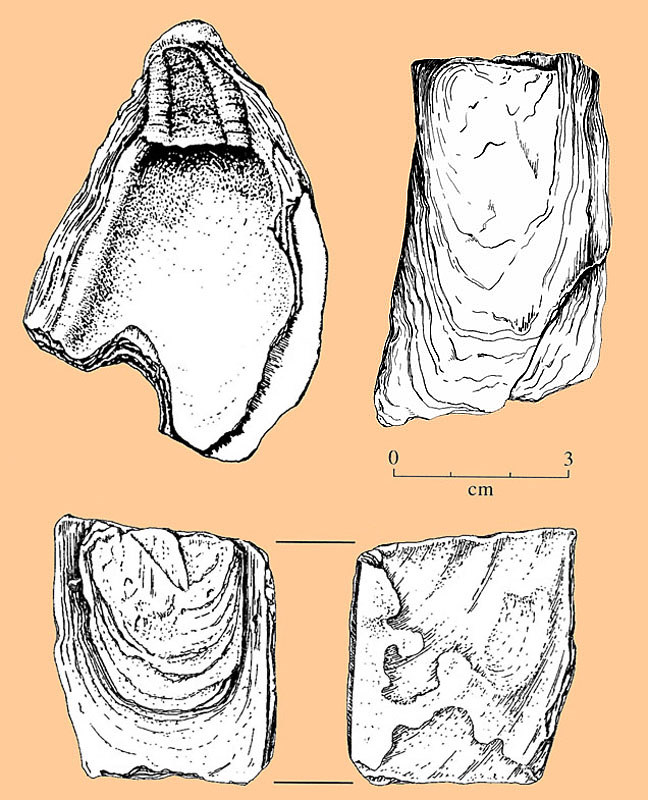

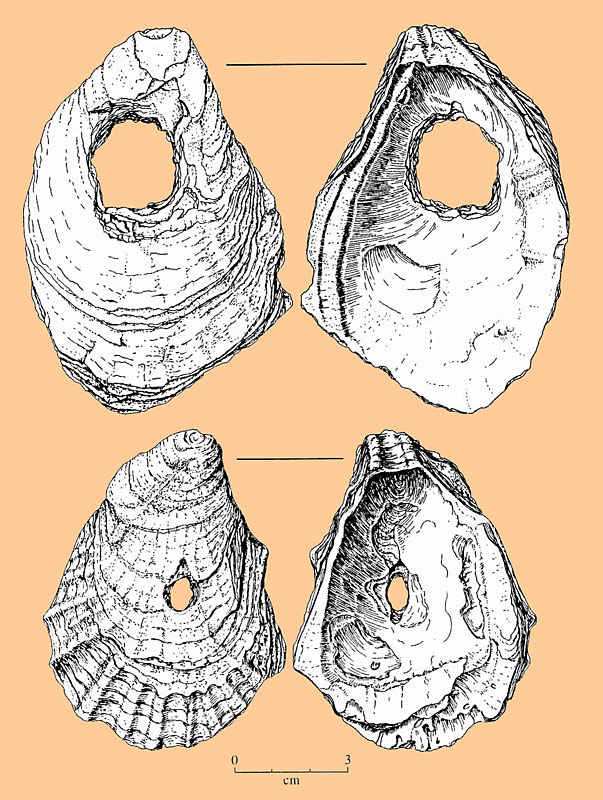

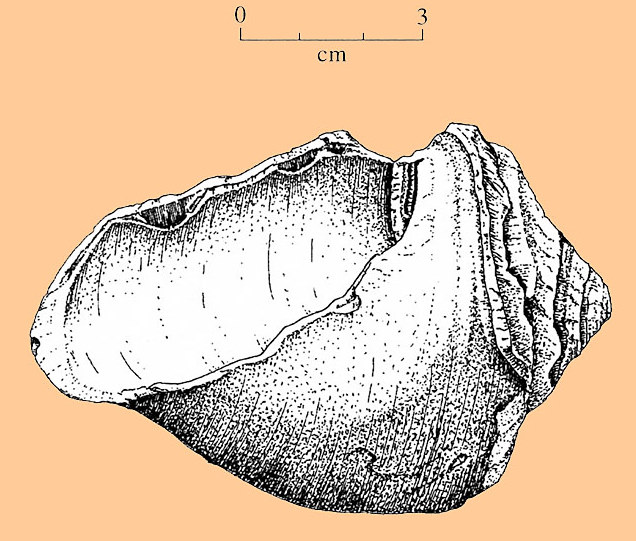

Oyster: The Crassostrea virginica species of oyster inhabits bays and estuaries along North America’s eastern seaboard, the Gulf states, Mexico, and the West Indies. Oyster tools have been found primarily in middens along the shores and barrier islands in the upper and central Texas coast, but are less frequently reported for the lower coast. Harvested primarily as a food source, the shell was only secondarily put to functional tasks. Naturally robust, oyster shell would have held up well to casual modification. Cabeza de Vaca may have offered oyster tools as trade items on his inland journeys as a trader.

Oyster shells were used as knives, scrapers, net weighs, awls, or possibly as hafted digging tools. Used in such ways, they exhibit a combination of notches, nicks and cut edges along one or more margins. Man-made alterations differ from naturally abraded oyster shells, which tend to exhibit smoothing over the entire valve surface.

|