Harris County Boys’ School

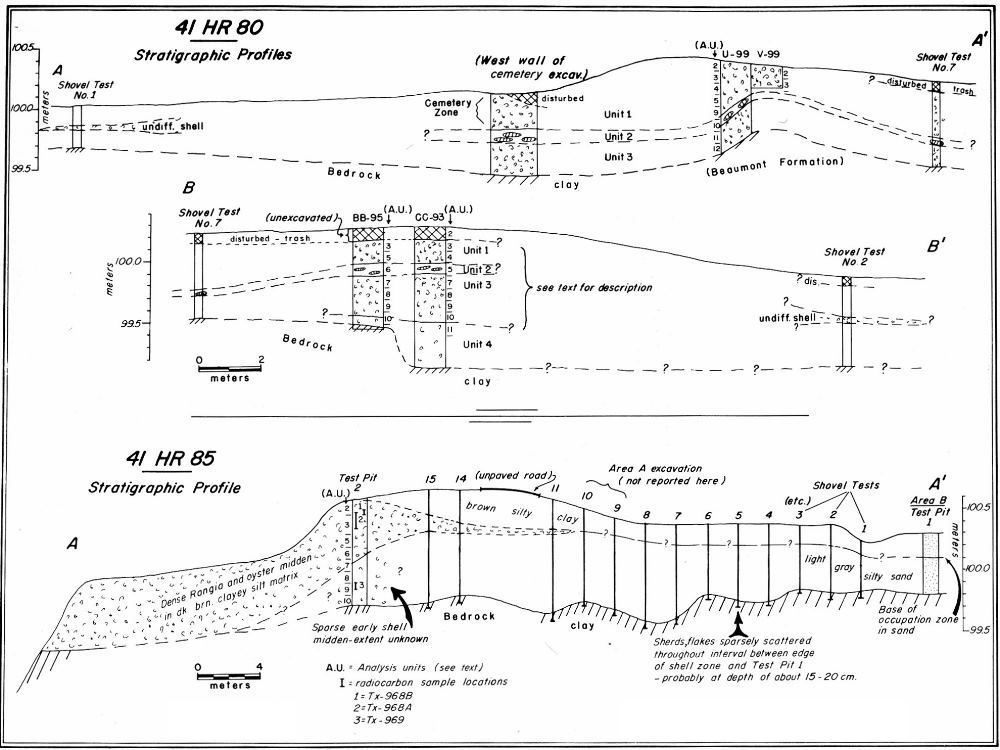

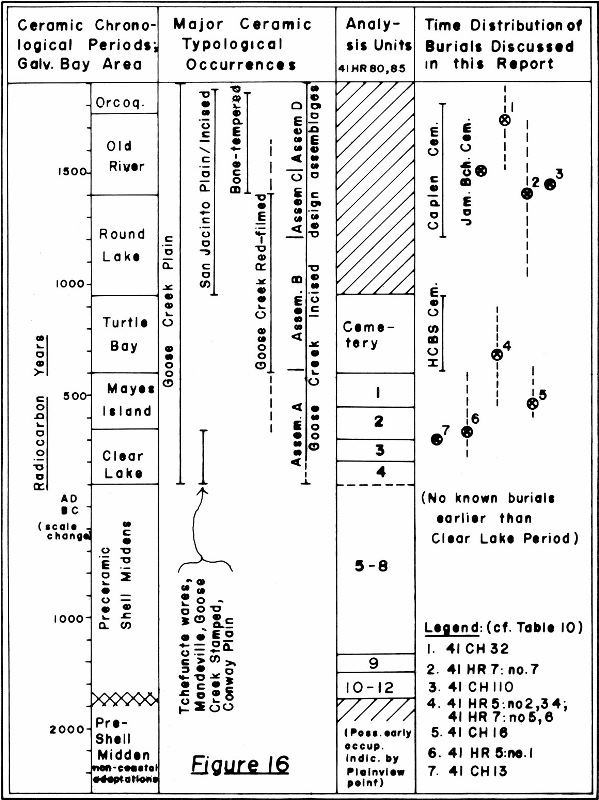

This site is located on the grounds of the former Harris County Boys’ School, on the western edge of Galveston Bay southeast of Houston. It consists of an extensive area of shell midden accumulations containing shell and other refuse discarded by native peoples, as well as a later cemetery. Although shell midden deposits covered the entire area, the site was given two site numbers; 41HR85 contained the most massive midden deposit, while the cemetery was confined to an area designated 41HR80. The midden, which was created between about 1500 B.C. until A.D. 500, represents one of the earliest known instances of the use of estuarine resources from the upper Texas coast. The later cemetery is one of only a few known from the upper Texas coast that contains grave offerings, making it important for understanding the mortuary practices of the prehistoric peoples of the Galveston Bay area.

The Harris County Boys’ School site was originally located by Richard M. Gramley, who tested the area around the Harris County Boys’ School in preparation for planned construction of new facilities in May 1968. Upon encountering human remains, he carried out brief excavations and uncovered 12 human burials, several of which were accompanied by artifacts. This discovery attracted considerable archeological attention to the site.

Lawrence E. Aten and a small team of archeologists from the University of Texas at Austin and volunteers from the Houston Archeological Society excavated the site more thoroughly during four separate visits between May 1969 and April 1972. Their work uncovered 20 additional burials in the cemetery and determined that the shell midden represented an earlier occupation of the site. Aten and his colleagues published a site report and the results of analysis of the human remains in 1976.

Occupation of the Harris County Boys’ School site began some 3,500 years ago (around 1500 B.C.). By this time, the Gulf of Mexico had reached its modern sea level and the Galveston Bay estuary was in its final phase of development. The estuary became an ideal habitat for oysters and Rangia clams, drawing prehistoric people to its shores. In addition to gathering shellfish, these early campers hunted, fished, and made and reworked bifacial stone tools, and the waste from their activities accumulated in the midden.

People returned to the Harris County Boys’ School site to camp and gather shellfish periodically over the next 2000 years. The campers also began to use a greater quantity and variety of stone tools as well as bone tools and beads. Shortly before abandoning the site around A.D. 500, they began using pottery.

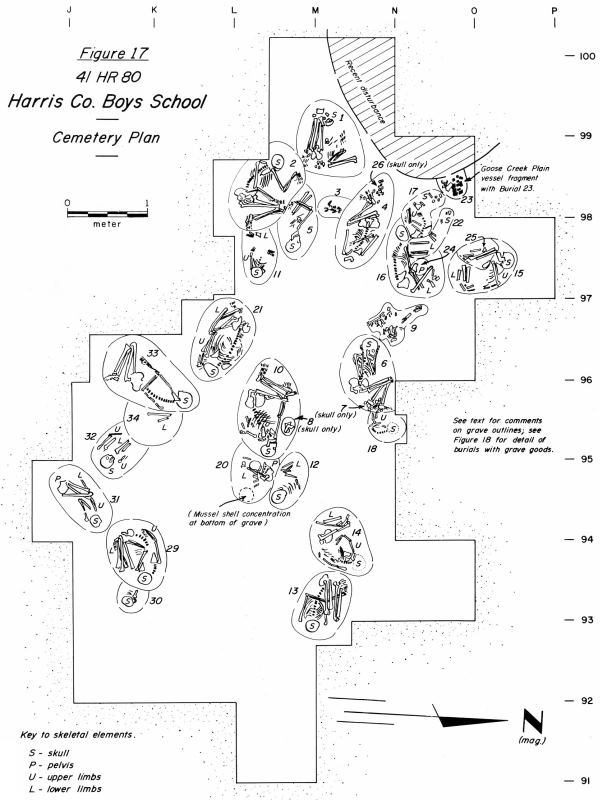

Between about A.D. 600 and 950 one area of the site was used as a cemetery, likely by people ancestral to the Akokisa (Orcoquisa) Indians who were encountered in early historic times in the Galveston Bay area. Of the 32 individuals buried at the Harris County Boys’ School site, 4 were infants (less than 2 years old), 3 were juveniles (2-10 years old), 2 were adolescents (10-20 years old), and the remaining 23 were adults. Only 3 of the adults are thought to have been over 40 years old, which is consistent with the widespread pattern among prehistoric hunting and gathering societies in North America: life spans were relatively short. Sex could be determined for 19 of the adults, of which 12 were male and 7 were female.

Judging by their bones, the people interred within the cemetery were in generally good health. They had limited instances of arthritis, broken bones, bone infections, and dental abscesses and cavities. The only unusual individual in this regard was a 22-25 year old male who lost the use of his right arm and leg several years before his death. The fact that the man was able to survive among mobile hunter-gatherers for a considerable amount of time after he was severely injured shows that he was cared for by members of his group.

All of the burials appear to have been primary inhumations, meaning that the deceased were carried to the cemetery soon after they died and their bodies were still intact. The bodies were laid to rest in flexed (bent knees and arms) or semi-flexed positions. Nearly three quarters of them were positioned with their heads pointing toward the east; the rest pointed toward the west. One of the infants (possibly a newborn) was placed inside a Goose Creek Plain ceramic vessel before burial. This is the only known instance of this method of interment from the upper Texas coast.

Most of the graves contained mussel shell (freshwater clam) and red ochre. Red ochre is not native to the coastal zone and would have been brought to the cemetery from elsewhere. The placement of blood-red pigments in graves is a worldwide prehistoric pattern with rather obvious symbolic connection. At Harris County Boys’ School, some instances, the ochre was scattered throughout the grave, and in others it was concentrated in a small area adjacent to the body (perhaps originally enclosed in a perishable container such as a leather bag).

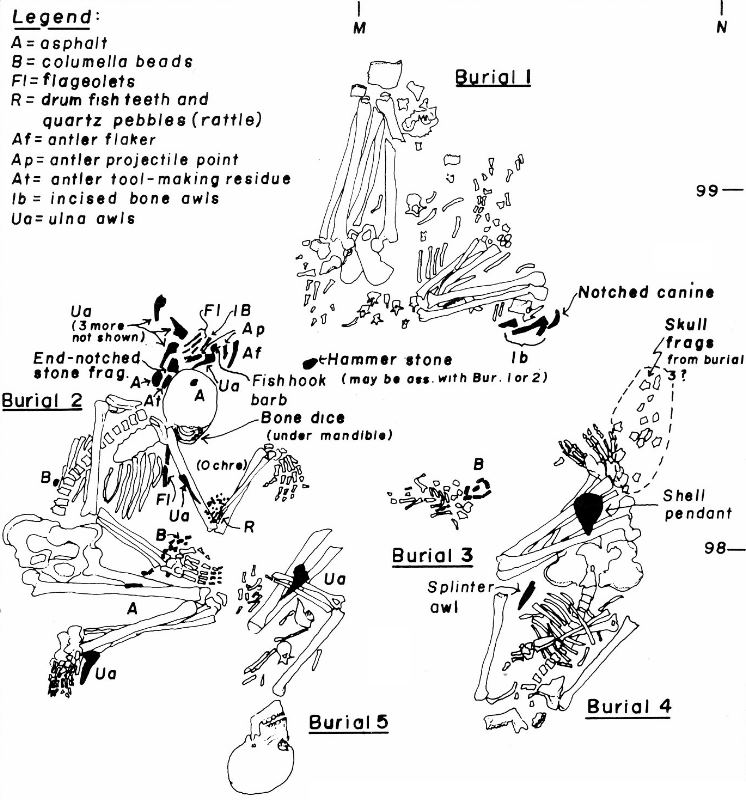

Twelve of the burials contained additional grave offerings, but there is no clear pattern of distribution of these items on the basis of age or sex. Three types of artifacts were found among the burials: implements, such as awls and fishing tools, items of adornment, such as shell beads and pendants, and personal items, such as bone flutes and gaming pieces. No grave contained artifacts belonging to more than one of these categories, with the exception of Burial 2 which contained all three.

The Burial 2 grave contained the remains of a 25-35 year old male accompanied by a shell bead bracelet, 5 bone flutes, 6 bone gaming pieces, 2 antler flakers, 3 antler projectile points, a bone fishing hook, an end-notched stone, an incised bone awl, several undecorated bone awls, and a cluster of 40 black drum fish teeth with 3 small quartz pebbles that may have once been part of a gourd rattle. The grave is unique among all known burials on the upper Texas coast in its quantity and variety of grave offerings. The man likely enjoyed considerable status within his social group; perhaps he was an important leader.

Though no clear pattern in the distribution of grave offerings can be discerned for the Harris County Boys’ School cemetery, when the data from the cemetery is considered with data from the other cemeteries in the Galveston Bay area, patterns in mortuary practice for the region do emerge. Grave goods appear in fewer than half of all the known burials in the Galveston Bay area, and do not appear in great numbers. Generally, graves do not contain artifacts belonging to more than one of the three types of grave goods defined above: implements, items of adornment, and personal items. Items of adornment accompany burials of all ages and both sexes. Personal items, on the other hand, appear only with adults and may have been considered items of personal significance or personal property. Implements also appear only with adults, and in many cases seem to represent craft or skill specialties and to reflect a sexual division of labor. Artifacts related to shell bead manufacture are associated with females, while those related to hunting, fishing, weaving, and stone tool manufacture are associated with males.

Contributed by TBH Editorial Assistant Carly Whelan, based on the sources below.

Sources

Aten, Lawrence E.

1983 Indians of the Upper Texas Coast. Academic Press, New York.

Aten, Lawrence E., Charles K. Chandler, Al B. Wesolowsky, and Robert M. Malina

1976 Excavations at the Harris County Boys’ School Cemetery: Analysis of Galveston Bay Area Mortuary Practices. Special Publication, No. 3, The Texas Archeological Society, Austin.

|

|