In this section:

|

This site in rugged Musk Hog Canyon in Crockett County (41CX131) contained the remains of a earth oven where historic native peoples used hot rocks to roast the nutritious "hearts" of desert plants, such as sotol, just as their prehistoric counterparts did for thousands of years. TARL archives. Click to enlarge and learn more.

|

| The Plateaus and Canyonlands region has a long and rich

archeological record of human cultures spanning more than 13,000

years. Oddly, it is the most recent of the native peoples

that we probably understand the least, based on archeological

remains. |

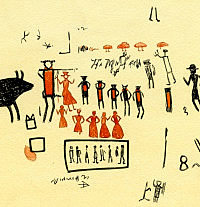

A Spanish mission looms from the tall canyon wall where it was painted by a historic native artist in a Val Verde County rock shelter (site 41VV343) in the Lower Pecos region of southwest Texas. TARL archives. |

Mission diet. Remains of charred corn and prickly pear (Opuntia sp.) seeds (top row) were recovered during excavations at Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz, suggesting the Indians-and possibly the Spanish occupants, as well, mixed wild plants with their domestically grown foods. Early accounts tell of priests and expedition leaders having to rely on native peoples to provide food, such as roasted agave hearts, during lean times. TARL archives. |

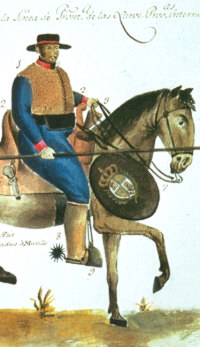

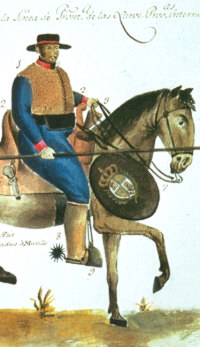

Spanish soldier on the Texas frontier. Watercolor painted by Ramón de Murilla, circa 1804, and included in his report to upgrade the condition of troops in New Spain. This image identifies suggested changes in uniform and armaments. Original painting, Archivo General del Indios, Seville. |

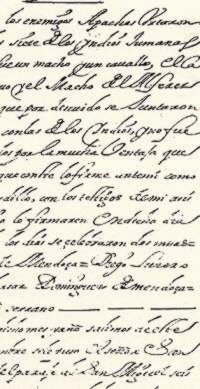

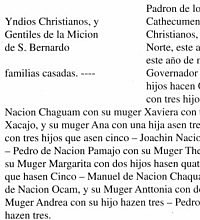

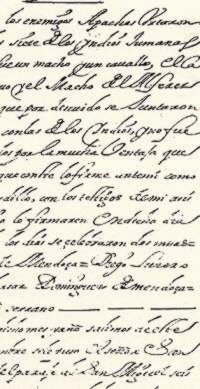

Page from the record of Juan Dominguez de Mendoza's expedition into Texas in 1684. |

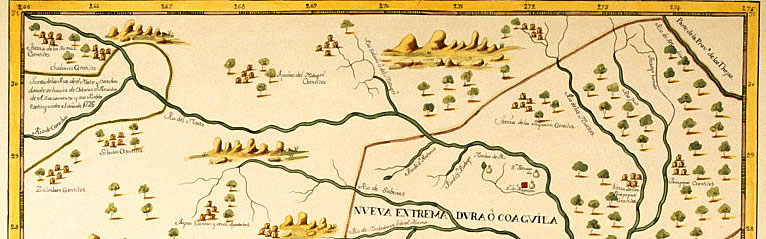

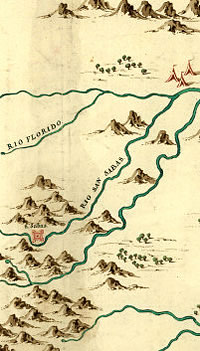

Plan map of Presidio San Saba, by Jose Urrutia, 1767. The

presidio was repeatedly attacked by hostile native peoples,

particularly the Comanche. On an inspection tour of the presidios

in Texas in 1767, Marques de Rubi sharply criticized the frontier

outpost: “This is a fortification that is as barbarous

as the enemy who attacks it.” Map, “ Plano Presidio

del San Saba,” original in British Library, London. |

Several times some horses were lost to the enemy Comanches

and their allies of the north. We stayed here until August 3

without other events, except for seeing the tracks of spies and

some smoke signals, by which they communicated their arrival

to one another. Marques de Rubi, July 25, 1767, Presidio San

Saba. |

Spanish documents record numerous sightings

of black bears on the Edwards Plateau. The animals were hunted

by Native Americans and Spanish explorers alike. Pelts of very

black bears, killed before winter, were highly valued by some

native groups. |

|

Historical researchers draw on many different

lines of evidence to paint the faint pictures we have of Texas’ native

peoples during historic times. Written documents, such as diaries

of missionaries or explorers; expeditionary maps, with their depictions

of native encampments; paintings and drawings, both by observers

as well as the native peoples themselves; and archeological evidence,

the physical traces left by native groups, all offer glimpses into

the past.

None considered alone provide a satisfactory rendering of any

one group. Taken together, however, the various pieces of information

help us understand what life was like for native peoples during a

critical juncture in their history. The Native Peoples exhibits

rely on a combination of ethnohistory—the

study of documents to describe and study groups that may or may not

have a written history—and archeology, the

study of past cultures based on the material evidence they left behind.

In this section, we look at examples of the different types of information

and the larger picture that is cumulatively revealed.

The Archeological Record

Archeological excavations

indicate that people have lived in the Plateaus and Canyonlands region for the last

13,500 years. Their material culture

shows that they were clever, industrious individuals, living in groups

and ably sustaining their families and group members by fishing in

the rivers and streams, hunting deer and other mammals for meat and

hides, and roasting large bulbs of sotol and lechuguilla. The beautiful

rock art they painted tells us that they had a rich spiritual tradition

as well.

Yet, oddly, it is the most recent of these native

peoples—the people who occupied the region when Europeans came to northern Mexico and Texas—that we probably

understand the least, based on archeological remains. Only a handful

of sites have been identified that can be related

to recent native occupation of the region. Remarkably, some of these sites, such as 41CX131 excavated in Crockett County in west Texas,

indicate the continuation of a similar lifeway and subsistence over

thousands of years. There, an earth oven was used by native peoples

perhaps as recently as 300 years years ago to roast the hearts (stem bases) of desert plants, a practice employed by native peoples in Texas for more than 8,000 years.

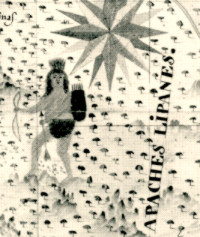

A quite different lifestyle is suggested in the findings from Infierno Camp in Val Verde County. Archeologists have identified the remains of a large encampment with what appear to be more than120 wickiup rings (small rings of stone of less than 3 meters in diameter) and 7 large tipi rings (circles of stone measuring from 3 to 10 meters in diameter.) The stones were apparently placed to hold wood supports for the shelters; in the case of the large rings, they may have supported large wooden poles for tall, hide-covered tipis. A remarkably low frequency of burned rock at this and other "Infierno phase" sites stands in sharp contrast to the older, more prevalent burned rock midden sites with their large heaps of spent cooking stones. There are few artifacts, other than sherds of pottery and occasional chipped stone arrowpoints, such as Perdiz and and no acceptable radiocarbon assays to date these sites. The large tipi rings, however, point to a time when native peoples were moving their camps with the aid of horses. Other sites are rock art sites of the historic period, with

vivid depictions of figures in European garb, horses, and mission-like structures.

Investigations of contact sites—places where native peoples

encountered or lived with Europeans, such as Spanish priests or settlers—show

that native customs were practiced even in mission contexts. At the

site of Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz (see Historic Encounter exhibit) in Uvalde

County, archeologists found chipped stone tools and late-period triangular

arrow points inside the structure. They also found gunflints, likely

made by the Lipan Apache who were living there.

Documentary Evidence

Most of our knowledge of native peoples in the region comes from the records kept by Spanish priests and government officials. In comparison to other parts of the state, however, expeditions

into the Plateaus and Canyonlands were few and records scant. The

dry, desert conditions of the region generally were viewed as undesirable by both the Spaniards when they claimed these lands in the sixteenth century

and by the Americans who came overland or by sea to settle in Texas

during the nineteenth century.

Economics and the need for cheap labor drew some of the first expeditions. During their first 100 years of colonization, the Spanish discovered

rich silver deposits in Mexico about 300 miles south of modern Texas.

Miners flocked to those mines to find work and, hopefully, wealth.

But, silver mining required large labor forces and Spanish labor

was inadequate to fill the need. As a result, many Indians were pressed

into labor, and many of the earliest encounters of the native peoples

with Europeans were during hostile Spanish raids to capture and enslave

Indian workers.

The first Spanish expedition into the Plateaus and Canyonlands that

was not for the purpose of capturing slaves was that of Gaspar Castano

de Sosa in 1590. Departing from Mexico, he took men, women, and children via wagon train

to settle in New Mexico. His route was from Almaden (today Monclova,

Mexico) north-northwest to the region of Santa Fe in New Mexico.

Had he known the difficulty this route would cause the expedition,

he might have had second thoughts. Researchers believe

that his route took him across the Rio Grande at Del Rio. Up to this

point, the expedition had encountered little trouble.

Water was sufficient and the topography mild. However, once they

left the Rio Grande, their travel was plagued by the ravines and

canyons that dominate the region. They could see water in the ravines,

but could not reach it. De Sosa' s experience exemplifies the challenges of the canyonlands terrain.

We continued in search of the Rio Salado [ Pecos River], the

object of our journey; and Captain Cristobal de Heredia sent out

[several men] for this purpose. They succeeded in finding the river,

which pleased them very much. Domingo de Santiesteban came back

to convey the good news that he and his companions had at last

discovered the Salado [Pecos River], although it was impossible to reach it because

of the many high rocks and gullies. We spent the night in a ravine

where there was a pool that supplied water for our people….

We tried every means of reaching the stream, but to no avail.

While the expedition eventually reached New Mexico, the journey

was grueling. Accounts of the route, describing the hardships, were

circulated shortly after the trip and no Spaniard ever repeated

this route to New Mexico.

Castano de Sosa reported seeing only a few native peoples during his journey. They found “rancherias” (a

small camp or hamlet) and huts, but rarely found them occupied. It

was only when they finally were able to descend to the Pecos River,

likely in the vicinity of Sheffield, Texas, that they came upon a

group of people who called themselves “Depesguan,” a

name that apparently was not used again. These people gave the Spanish buffalo

meat and chamois skins and used dogs to carry their camp supplies.

Beyond this, we know little of the people encountered by de Sosa.

Later expeditions record more contact with native peoples. Juan

Dominguez de Mendoza’s expedition from 1683-1684 was made in

response to requests by the Jumanos and their allies for protection

from the Apaches and for increased Spanish settlements and friars. Mendoza's journey from El Paso del Norte to southwest Texas and on to the

eastern Edwards Plateau provides vivid descriptions of encounters

with aboriginal peoples, particularly with lesser known native groups

such as the Gediondo (or Jediondo).

When the expedition neared the

ranchería on the east side of the Pecos River (in present-day

Crockett County), they were met with a joyful ceremony. The captains

of the Gediondo, mounted on horses, came out to welcome them; other

natives on foot carried a heavy wooden cross painted in red and yellow

and a flag of white taffeta decorated with two blue crosses. They

kissed the frocks of the friars, and both groups proceeded toward

the rancheria where they were welcomed by the majority of the women

and children with shouts and expressions of happiness. Several huts

made of tule reeds were offered to the visitors, although Mendoza

declined to use them.

The writer found the Indians to be “docile and affectionate,” although

greatly fearful of the Apache. The party was given food and deer

skins, and during the week-long stay, they killed 24 buffalo. An

assembly was held with other Indian groups who pleaded with Mendoza

to make war on the Apaches.

Many accounts reported threats of hostilities with groups such as

the Comanche, including raids on the expedition camps. Marques de

Rubi, while conducting an inspection tour of the presidios from 1776

to 1768, traveled over the Edwards Plateau to visit Presidio San Sabá.

July 25. … To conduct the inspection of the presidio,

we were in constant danger and constantly had to guard the horse

herd. Several times some horses were lost to the enemy Comanches

and their allies of the north. We stayed here until August 3 without

other events, except for seeing the tracks of spies and some smoke

signals, by which they communicated their arrival to one another.

Marques de Rubi, July 25, 1767.

During their journeys, many Spanish travelers made notes on the

natural world—the region’s varied terrain, plants, and

animals.

Rubí writes:

August 4, 1767. We went constantly downward until

reaching the Rio de Janes ( Llano River). This day we found enormous

numbers of small bison herds, to which we gave chase and killed

four. Also, a bear was roped and caught alive, and three wild

turkeys…, all of

which was a great bounty for the convoy.

Swiss botanist Jean Louis Berlandier, traveling with the Mexican

Boundary Commission in the early 1800s, accompanied a party of Comanches

on a bear hunt near the headwaters of the Medina River. He noted

two varieties on bear in Texas at the time,

These documents contain wonderful information but they are also

flawed in some respects. They present the native peoples from the

writer’s unique perspective. Few of the early travelers could

speak native languages, and the native people who spoke Spanish,

at least in the earliest encounters, understood those languages imperfectly.

Thus, when we use these documents to make better sense of the past,

we must accept their inherent flaws. |

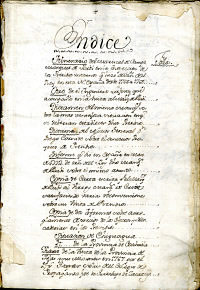

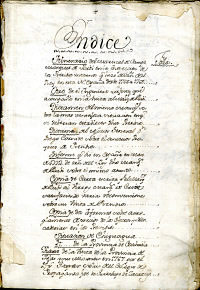

Front page from diary of the Marqués de Rubí, made during an inspection tour of presidios in Texas and the northern frontiers of New Spain between 1776 to 1768. Diaries and journals of government officials and priests often contained important information on native peoples and the environment in which they lived. Image courtesy of the Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin-CN 08492.

|

Circles of stone, such as the one pictured above, covered

large portions of this site in Val Verde County. Archeologists

believe the area was the site of a large encampment in historic times; they

have identified more than 125 wickiup (small shelter) rings and 7 large

tipi rings. According to historic accounts, native peoples lodged stones

around the supports for the shelters (branches , in the case of wickiups,

and tall wooden poles, in the case of tipis) to hold them firmly in place.

Photo by Steve Black. Click to enlarge.

|

Chipped stone gunflints for flintlock firearms, likely

made by Lipan Apache knappers. The flints were recovered during

archeological excavations at the site of Mission San Lorenzo de

la Santa Cruz, a Spanish mission for the Lipan on the San Saba

River from 1762-1771. Investigations there and other mission sites

in Texas indicate native peoples continued traditional practices,

such as making chipped stone tools and arrow points, even while

growing crops and learning the Christian rituals of the Spanish

priests. Photo by Susan Dial. TARL collections. Click for more

examples. |

The torturous terrain and arid conditions of the canyonlands area made Spanish expeditions north of the Rio Grande grueling, as Gaspar Castano de Sosa was to discover in 1590 when he attempted to bring a wagon train across the Pecos River and on to New Mexico.

|

Mines being worked by Spanish slaves. Many native peoples were captured by the Spanish to work silver mines in Mexico during the early years of colonization. The image shown depicts a scene in Peru. |

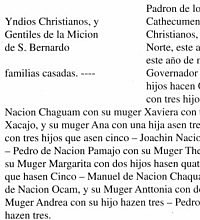

Transcript from sacramental records of the 1700s-1800s at Mission San Bernardo, Mexico, showing types of information available from such resources. From Kenmotsu and Wade 2002: Fig. 5. |

The captains of the Gediondo, mounted on horses, came out

to welcome Mendoza; other natives on foot carried a heavy wooden

cross painted in red and yellow and a flag of white taffeta decorated

with two blue crosses. They kissed the frocks of the friars,

and both groups proceeded toward the rancheria where they were

welcomed by the women and children with shouts and expressions

of happiness. |

Comanche couple, as depicted by Lino Sánchez y Tapia, based on drawings of Indians made during a Mexican scientific expedition into Texas from 1828-1829. A group of Comanches from San Antonio led the party onto the Edwards Plateau to hunt for bear, and the trek was excitedly described by Jean Louis Berlandier in his journal. |

|