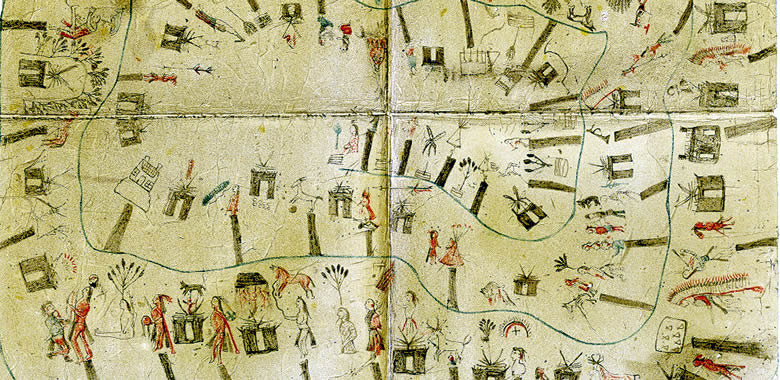

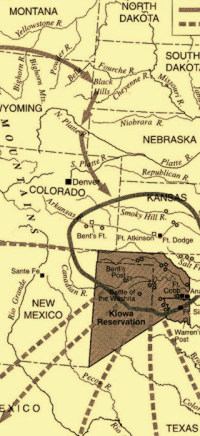

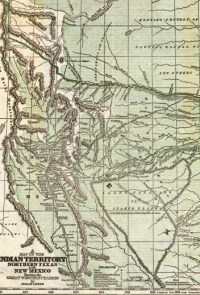

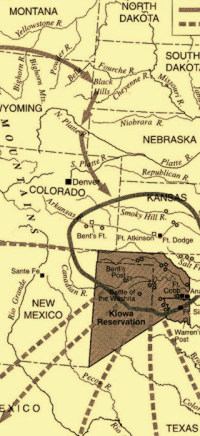

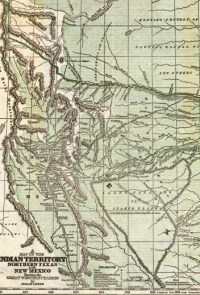

Migration of Kiowa peoples from the north in the 18th century to southern Plains in the 19th century. Shown are reservation boundary, raiding trails to south into Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico, and locations of annual Sun Dance, the major Kiowa religious ceremony. (Map adapted from Levy 2001.) |

The name "Kiowa" derives from the English spelling of "Ka'I gwu," meaning "principal

people." |

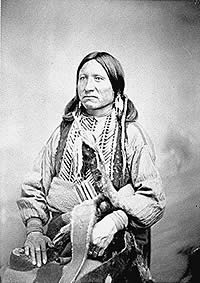

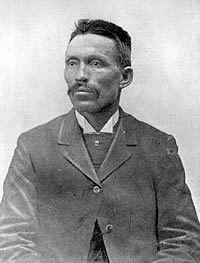

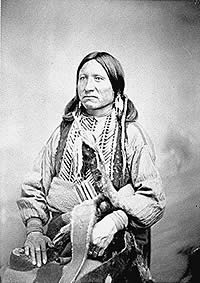

Kicking Bird (Tene'-angp6óte), a Kiowa chief and grandson of a Crow captive. Interviewed in the late 19th century, the chief told of the Kiowa's origins far to the north and of a time before there were horses to help move families from place to place. Photograph by William S. Soule, circa 1870. Original image in National Archives. |

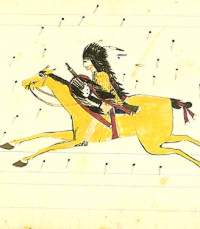

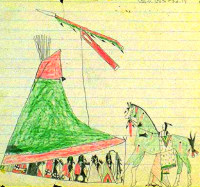

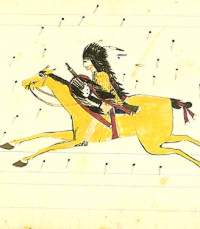

The introduction of the horse to North America changed the lifeways of Plains Indians, making buffalo hunting, moving camp, and engaging enemies easier. 1875 drawing of a Kiowa on horseback and symbols denoting fired musket balls by Koba, a Kiowa imprisoned at Fort Marion, Florida, following the Southern Plains Indian Wars. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution INV 08547608. |

Teh-toot-sah, one of the Kiowa encountered by artist George Catlin, reportedly in an encampment along the Red River, Indian Territory, in the 1830s. The Kiowa was described by Catlin as the head chief of the Kioways (sic), " a very gentlemanly and high minded man, who treated the dragoons and officers with great kindness while in his country. His long hair, which was put up in several large clubs, and ornamented with a great many silver broaches, extended quite down to his knees." |

Big Tree, Kiowa leader involved in the attack at Howard's Well as well as in the Warren Wagon Train massacre in northwest Texas. |

Howard's Well, a stage stop on the Southern Overland Mail route, was the target of repeated attacks by Indians throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The well-springs enclosed by limestone walls-was an important water source for travelers crossing the parched terrain. The jacal building shown above may date as early as the 1860s; a previous station on the site was destroyed by Comanches in 1861. Photo by Claude Hudspeth, TARL Archives. |

|

The Kiowa originally lived on the northern

Plains of Canada and moved south into the Southern and Rolling Plains

of Texas and Oklahoma in recent historical times. Prior to their

forced placement on a reservation in the 1870s they were, like other

Plains tribes, semi-nomadic, moving in relatively large groups and

frequently in the company of one or more tribes with whom they were

allied.

“Kiowa” derives from the English spelling of Ka’I

gwu, and in their language it means “principal people.” The

Kiowa language is part of the Kiowa-Tanoan language family. Tanoan

languages are those that were spoken in the Jemez, Piro, Tiwa, and

Tewa pueblos of New Mexico. Linguists who study the history of languages,

however, believe that Kiowa split from Tanoan branch over 3,000 years

ago. Thus, at some time in the past they moved to the far north or

the puebloan groups moved a considerable distance to the south prior

to the arrival of the Kiowa in the Southern Plains.

Kiowa Migration

By the early eighteenth century the Kiowa were living in the area

between the Platte and Kansas rivers well to the north of Texas.

From there they slowly moved further south, eventually becoming roaming

the lands north of the Canadian and Red rivers in Texas and Oklahoma.

In the late 19 th century, elders could still speak of their lands

far to the north. In the words of Chief Kicking Bird, in 1871:

The Kiowas, many years since, lived far to the north where it

was very cold most of the year—far beyond the country of

the Crows and the Sioux….They lived there, knowing nothing

of ponies, but used dogs to carry their burdens, to draw their

lodge poles, and remove all their fixtures from place to place.

He told a story of how the Kiowa were introduced to horses and

to the possibility of better lands to the south:

In the process of time one of their [Kiowa] men, in his travels,

went far to the southward, and after some years of roaming, was

taken prisoner by a band of Comanches. They took council to put

him to death, but one of their head men prevailed…on the

plea that they had never before seen anyone like him or any of

his people, and it might be that if they treated him well, he might

befriend any of their men who might fall in with his tribe….The

counsel of this chief prevailed, and [the Kiowa man] was fitted

out with a pony, saddle, and bridle and was sent home. On his return

[to the Kiowa people], his pony, saddle, and bridle were objects

of general admiration and envy….He told them that in this

country he had visited, the summer lasted nearly the whole year,

and the plains were well stocked not only with game, but large

herds of ponies such as he was riding.--Kiowa Chief Kicking Bird,

1871.

Like other oral history accounts, some of this may not be exactly

how events unfolded. However, we do know that among tribes on the

northern Plains in the 18 th century there existed relatively fierce

competition for buffalo and other resources. Some tribes may have

felt the need to venture further south where resources may not have

been as scarce. To transport their camps from place to place, dogs

were used as pack animals until horses became available from the

Spanish settlements to the south. Following buffalo herds into the

Southern and Rolling Plains of Oklahoma and Texas, the Kiowa established

a lasting bond with the Comanche and other tribes.

Over the ensuing decades, the Kiowa began to raid south into the

Plateaus and Canyonlands, along with their allies, the Comanche,

and other native people. By the late eighteenth century, they may have

been present in small numbers in the San Antonio area. One Spanish

document from 1784 lists the Sciaguas among the various native peoples

that were then present at Mission San Antonio de Valero. While the

name may be an aberration of one of the many groups from Coahuila,

its spelling appears to be a variant of the word Kiowa (Caigua or

Ka’I gua).

In the 19 th century, the Kiowa frequently traveled through the

Plateaus and Canyonlands going to and from Mexico. By the 1820s,

the Kiowa were raiding into South and Central Texas usually in consort

with the Comanche. As the nineteenth century progressed, the two

tribes were often encountered in the Southern and Rolling Plains

regions of Texas. Josiah Gregg’s 1844 Map of the Indian

Territory, Northern Texas and Mexico, showing the Greater Western

Plains depicts all of the Texas Panhandle as well as part of

Central Texas to be the territory of the Kiowa and their allies,

the Comanche.

George Catlin, an artist who traveled in the west in the 1830s and

painted portraits of the Indian tribes he met, encountered the Kiowa

while he was staying near modern Lawton, Oklahoma. He described them

as “much finer looking race of men than either the Comanchees

[sic] or Pawnees—[they] are tall and erect, with an easy and

graceful gait—with long hair….They have generally the

fine and Roman outline of the head.

In 1844, Texas Indian commissioner Robert Neighbors was told that,

while the Kiowa lived well to the north, when the leaves fell they

would be found in the vicinity of San Antonio. Neighbors reported

he found them between Pecan Bayou and the San Saba, the northern

portions of the Plateau and Canyonlands, in 1847 and 1848. He stated

that, with their allies, “they number (sic) 5,000 strong.” A

map in the National Archives shows the Kiowa and Comanche as the

principal tribes ranging from the Rio Grande to the Red River and

between the Pecos and Laredo, including the Plateau and Canyonlands.

During those years, the Kiowa were often part of the cohort in Comanche

raids. In addition to capturing horses, the Kiowa likely were gathering

peyote on these raids to the southwest. Peyote was important to the

Kiowa spiritual practice, and the plant could only be found far from

the Plains, in the desert areas to the southwest. The Rio Grande

River represents the northern-most limits of the plant’s growth.

Kiowa presence in the Plateaus and Canyonlands waned in the succeeding

decades. After 1860, the Kiowa rarely ventured into the region, remaining

to the north in the lands for which they are better known. Notable

exceptions occurred in 1860, 1872, and 1873. In 1860, a member of

a Kiowa band on its way to raid in Mexico was killed while attempting

to steal horses near the Pecos River. Then, in 1872, a Kiowa/Comanche

raiding party attacked a government wagon train at Howard Wells near

the Devil’s River, and another Kiowa/Comanche band traveled

to Mexico below Eagle Pass. On their return via the Devils River,

they encountered an Army scouting party that killed two of their

members. This battle may be immortalized in the rock artat

41VV327, a site located on a tributary of the Devil’s River. |

Other names for Kiowa:

Ka'i gwu, Caygua

Caigua, Kioway, Kinway

Ga'taqka, Cataka, Gatacka

Ka-ta-ka, Padouca

|

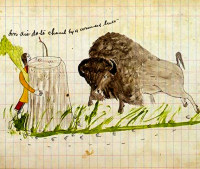

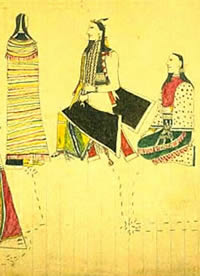

Kots-a-to-ah, or Smoked Shield, as painted by George

Catlin on the Red River of Texas circa 1830s. The frontier artist described

the Kiowa leader as "another of the extraordinary men of this tribe, near

seven feet in stature, and distinguished, not only as one of the greatest

warriors, but the swiftest on foot, in the nation. This man, it is said,

runs down a buffalo on foot, and slays it with his knife or his lance, as

he runs by its side!" |

The Kiowa are a "much finer looking race of

men than either the Comanchees [sic] or Pawnees-[they] are tall

and erect, with an easy and graceful gait-with long hair..They

have generally the fine and Roman outline of the head."-George

Catlin |

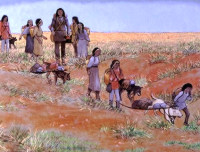

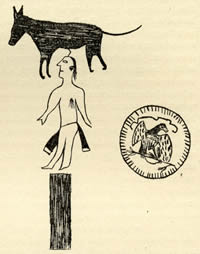

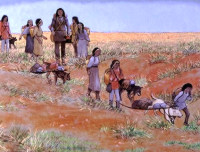

Moving camp. The Kiowa, like other Plains tribes, depended on dogs hitched to wooden sleds, called "travois," to move their camp equipment from place to place. Inset of painting by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Original mural at Lubbock Lake Landmark, Lubbock. |

By 1844, the territory of the Kiowa was interspersed with that of their allies, the Comanche, and the two groups raided from the Texas Panhandle to the Gulf coast. Inset from Map of the Indian Territory, Northern Texas and Mexico, showing the Greater Western Plains by Josiah Gregg. Click to enlarge. |

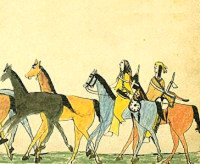

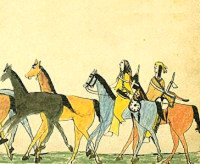

Kiowa herding horses captured during raid in Mexico? An 1875 drawing by Koba, one of the famed Fort Marion, Florida, prison artists. Click to see full image. |

Toro-Mucho, chief of a band of Kioways. Woodcut made in 1854 during the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. Courtesy Texas State Historical Association, in Emory 1987:88. |

Wun-pan-to-mee (the white weasel), a girl; and Tunk-aht-oh-ye (the thunderer), a boy; who are brother and sister. As described by the artist, George Catlin, the two are Kioways (sic)who were purchased from the Osages, to be taken to their tribe by the dragoons (with whom Catlin was traveling in the 18302-1840s.). |

|