Setting

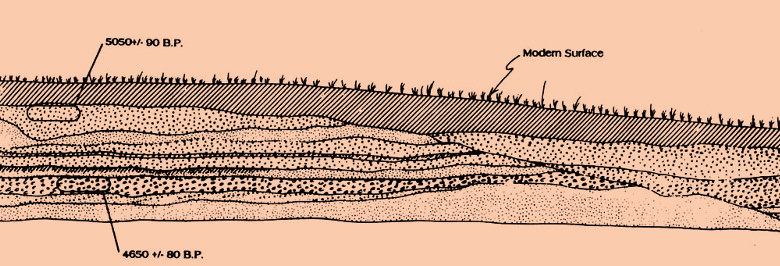

Schematic cross-section showing the evolution of Galveston Island. Based on Rodriquez et al. 2004 and Fisk et al. 1972. |

A geological profile from the west end of the Mitchell Ridge site shows that the core of Galveston Island was formed by deposits of fine sand and shell hash (pulverized seashells). These sediments were piled up by wave action and long-shore drift and then reworked and spread across the developing island by storm surges. Two radiocarbon dates obtained from samples of shell hash seem to show a stratigraphic reversal (the older date should be that from the lower deposit). This, however, is easily explained - some of the shells pulverized by wave action were from reworked older deposits. All of the human occupation of the site is found in the uppermost deposit, a fine cumulic (gradually accumulating) sandy soil some 40-60 centimeters (16-24 inches) in thickness. Adapted from Ricklis 1994, Figure 2.2. Enlarge to see legend.

|

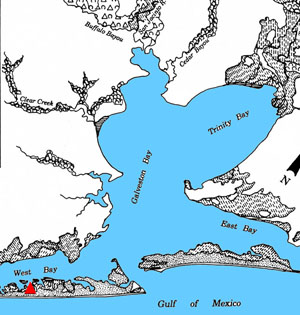

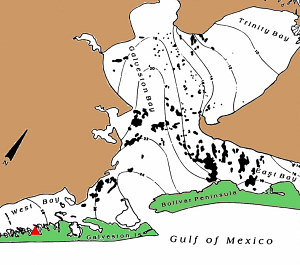

Galveston Bay Area EcologyGalveston Bay and its associated secondary bays and lagoons comprise an extensive and highly productive estuary environment. It is an example of the kind of low relief, protected estuary systems that are among the most biotically productive environments in the world, rivaled only by tropical rainforests. Galveston Bay waters are shallow and characterized by high photosynthetic primary productivity. In essence, sun + sheltered warm water + nutrients = fertile growth of plants and animals all the way up the food chain, as those who harvest Galveston Bay's oysters, shrimp, crabs, and fish today can well attest. The barriers of Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula protect the estuary environment from high energy wave action from the Gulf, and maintain moderate salinities. The shallow bays provide excellent habitat for grass beds and salt marshes. The freshwater rivers and bayous that empty into the bays bring nutrients and organic material and support brackish marshes. The wetland marshes and grass beds serve as nursery areas for primary consumers, such as shrimp, crabs, and mollusks. These creatures in turn support a range of secondary consumers such as fin fish, including the species which were used most heavily by native peoples such as black and red drum. The organic debris and nutrients from the marshes, grasses, and the Trinity and San Jacinto Rivers results in Galveston Bay having the most abundant supply of commercial shellfish on the Texas coast—oysters. Reefs of the American oyster (Crassostrea virginica) are large and abundant in Galveston and East Bays and somewhat less so in West Bay due to higher salinity. They are absent in the upper bays, such as Trinity Bay, because of the influx of freshwater. The brackish water clam, Rangia cuneata, is today found in the uppermost bays and along the lower rivers, streams, and bayous where relatively low salinity predominates. The presence of sizeable shell middens (piles of food debris comprised mainly of discarded shells) throughout the Galveston Bay area shows that native peoples made heavy use of both oyster and rangia. Individual middens are usually dominated by one species or the other, reflecting nearby water conditions at the time of occupation. The most economically important fin fish species to native peoples appears to have been black drum, red drum (redfish), sheepshead, and trout, in about that order. The drum spawn in the cool seasons from fall (redfish) to winter and early spring (black drum) when they are concentrated in the bays and tidal passes. Both species of drum grow quite large, with adults weighing 5-10 pounds and more. The bays support large numbers of waterfowl, particularly in the cooler months when ducks, geese, and cranes migrate from the north. Based on the animal bones found at archeological sites, native peoples in the Galveston Bay area did not depend heavily on waterfowl. Terrestrial (land) environments in the Galveston Bay area can be divided into three distinct zones: the coastal prairies, the riverine floodplains and deltas, and the barrier islands. The prairies are low and flat and have heavy clay soils that originally supported savannas (grasslands with patches of brush and trees) dominated by coastal prairie grasses such as big bluestem and indiangrass. Coastal bluestem grass is more common in sandy areas along the mainline shores. The coastal prairies supported numerous mammals, including four species heavily hunted by native peoples: white-tailed deer, eastern cottontail, jackrabbit, and, sometimes, bison. The floodplains of the major streams such as the San Jacinto and Trinity Rivers are biotically rich and diverse. River valleys support dense woodlands and forests of water oak, cedar elm, and sugarberry (commonly called hackberry). Oak-pine forests are found on higher terraces. The low-lying floodplains are lined with rushes, cattails, and willows. Swampy areas support bald cypress and palmetto palm. The riverine floodplains and deltas support all sorts of animals from deer to river otters to alligators to freshwater and brackish water fishes and shellfish. Until modern times, the barrier islands (including Bolivar Peninsula, which although connected to the mainland, is effectively a barrier island) were essentially treeless, except for small mottes of live oak and clumps of mesquite scattered along the higher ridges. Most trees were typically swept away during major hurricanes. The few spots with prominent trees served as navigation markers. Most vegetation consisted of salt-tolerant grasses such as cordgrass and glasswort.

Early 19th century visitors found Galveston Island to be teeming with life. Relatively few mammals inhabited the island, the most common being the hispid cotton rat, but deer were also present in periods between major hurricanes. Freshwater and brackish ponds formed in the mid-island swales and were lined by cattails and marsh grasses. These held frogs, crabs, turtles, water moccasins, and alligators. The ponds allowed dense clouds of mosquitoes to form in warm, wet weather. Amid the thick grasses were many snakes including rattlesnakes. Archeological and ethnohistorical evidence shows that the native peoples who buried their dead at Mitchell Ridge had a mobile lifestyle and probably lived on Galveston Island only during certain seasons of the year. Within a few hours travel by canoe and foot, however, they had access to contrasting environments and diverse resources from the bays, marshes, rivers, and prairies. |

|