The Guadalupe Bay site was first recorded in 1966 by avocational archeologist E. H. (Smitty) Schmiedlin of Victoria, Texas, and given the name “Heyland site” after the landowners of that time. It was reported to be a shell midden that sloped gradually downward from the edge of the Beaumont Formation on the east to the recently dredged Victoria Barge Canal on the west, and covered an area of about one acre. A few small looters’ holes were noted across the site, and a small artifact collection was made including stone tools, aboriginal pottery, glass, and worked shell.

A year later, Cecil A. Calhoun, another active avocational archeologist of Victoria, filed a highly entertaining, updated site record form in which he described falling into a nest of juvenile rattlesnakes from which he somehow managed to escape without a bite. Included on the form was a detailed description of a test pit he excavated. At that time, Calhoun described the site as a “marine shell midden” covering an area measuring 500 ft long by 100 ft wide. He noted that about half the locale had been disturbed by looting, and that a portion of the site had been removed during canal construction. Calhoun gave the site the name, “Guadalupe Bay,” by which it has come to be known.

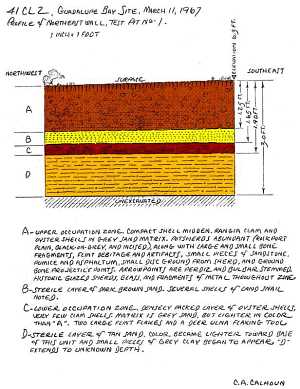

Calhoun’s test pit was a 5-by-5-ft-square unit placed into the center of the site below the adjacent Beaumont Formation terrace. Four distinct strata were revealed in the excavation. From top to bottom: (1) an upper midden composed of both the brackish-water clam Rangia cuneata and the more saline American or Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), extending from the surface to a depth of about 1.25 ft, with abundant artifacts including Rockport ware ceramics, faunal material, pumice, asphaltum, bone points, Perdiz and Bulbar-stemmed arrow points, and historic items, such as glass, glazed pottery, and metal fragments; (2) a culturally sterile layer of sand a few inches thick; (3) a lower midden, between -1.65 ft and -1.90 ft, primarily composed of oysters, although a few rangia were present, that lacked ceramics, but included large chert flakes and a deer ulna flaking tool; (4) the underlying, culturally sterile, sandy subsoil, extending from -1.90 ft to the base of the test pit at -3.00 ft.

Thus, at least two cultural components apparently were present: a preceramic occupation and a later ceramic-bearing deposit. Calhoun also noted the presence in surface collections of scrapers, drills, sandstone, mano and metate fragments, glazed stoneware and earthenware, glass, musket balls, and the rim of a Spanish olive jar. This latter item allowed him to suggest the possible presence of a Contact period component at the site.

In 1974 James Corbin incorporated data from Calhoun’s research into an overview of cultural succession along the central Texas coast. Corbin recognized the existence of an extremely late cultural pattern marked by Rockport ceramics, Bulbar-stemmed arrow points, and historic European artifacts. This pattern occurred at several sites along the central Texas coast and seem to represent Indian occupation in early historic times. The following year, several of the “scrapers” collected by Calhoun were analyzed by Hester and Shafer who recognized these as specially prepared blades representing a unique coastal lithic technology developed to more efficiently make use of small nodules and pieces of chert that had been brought to the rockless coast.

Ten years later, known archeological sites situated along the Victoria Barge Canal were inspected on behalf of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) who were planning maintenance and widening projects that might damage cultural resources. The Guadalupe Bay site was one of the locales examined, and it was found to be suffering greatly from the effects of wave-induced erosion from barge traffic in the canal. This inspection paved the way for subsequent investigations funded by the Galveston District, USACE, in order to comply with Federal regulations.

One of the earliest investigations was a 1989 survey and testing project conducted by Coastal Environments, Inc., (CEI) of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, an archeological consulting firm. Certain designated locations within the Corps’ right-of-way (ROW) for the barge canal were examined during that study and seven sites were tested to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The Guadalupe Bay site turned out to be one of more significant of these locales.

1989 Testing

During CEI’s 1989 investigations, the Guadalupe Bay site was gridded, mapped, augered, and tested by two 1-by-1-m square units. In addition, a small surface collection was obtained from the eroding bankline along the edge of the barge canal, while the collections made by earlier investigators was examined and photographed. The surface material contained strong evidence of a Late Prehistoric Rockport phase occupation including examples of a core-and-blade industry along with Scallorn, Perdiz, Bulbar-stemmed, and Lozenge arrow points. The ceramics encompassed the full range of what were identified as both Goose Creek and Rockport series ceramics, including plain, black-decorated, and incised types and varieties. In fact, the site was considered remarkable for the quantity and diversity of its ceramics.

Historic artifacts recovered from the surface collections included a lead-glazed redware sherd, several sherds of flow-blue and plain whiteware, and one sherd of blue shelledge pearlware. The presence of the redware sherd, along with the sherd from a Spanish olive jar collected by Calhoun in 1967, suggested an occupation dating sometime between 1650 and the first half of the nineteenth century. The Spanish pottery may have come from a Spanish mission dating to the 1790s, Nuestra Señora de Refugio, which was thought to have been situated not far north of the Guadalupe Bay site The pearlware sherd was manufactured sometime between 1780 and 1830, and, likewise, may have been associated with the 1790s mission. The flow-blue whiteware sherds, on the other hand, which were produced between ca. 1840 and 1860, were representative of a mid-nineteenth-century occupation, and almost certainly could be related to initial Euro/American settlement following cessation of aboriginal activity in the region.

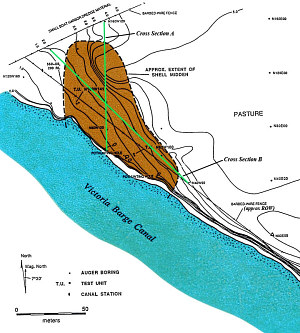

Initial subsurface investigations by CEI entailed drilling 16 bore holes with a hand-turned bucket auger to probe the depth of cultural deposits and determine the extent of the shell midden. Two crew members removed a succession of “plugs” from each hole, examining each plug and recording the depth at which distinctive deposits were encountered. Overall, the midden was found to cover an area measuring approximately 130 m northwest-southeast by a maximum of 55 m southwest-northeast. Approximately 20% of the midden lay within the Corps’ right-of-way (ROW), and occupied an area roughly 105 m long by 10 to 20 m wide. Evidence of aboriginal occupation was found to extend to a depth of 60 cm or more across much of the ROW.

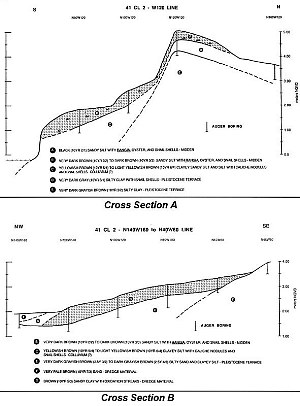

The auger boring was followed up by the excavation of two test units placed down within the ROW, one situated near the northwest end of the site and the other near the southeast end. In Test Unit N100 W141 (identified by the grid coordinates of its northeast corner), located about 10 m east of the western edge of the shell midden, the stratigraphy was relatively simple. There were two principal shell lenses, an upper midden (labeled Stratum 2) composed primarily of rangia, at a depth of between 10 and 30 centimeters below surface, and a lower midden (Stratum 4) between about 60 and 80 centimeters deep made up almost entirely of oyster. The strata above, between, and below the shell layers were thought to be of colluvial origin, having been washed down the nearby Beaumont terrace slope during periods of site abandonment. The greater clay content of the basal deposit (Stratum 5) suggested that it probably had developed through a combination of colluvial and fluvial processes.

The stratigraphy of Test Unit N62 W100, was very similar but there were three, rather than two, shell lenses: an upper midden composed of abundant oyster shells and a moderate amount of rangia(Stratum 2), a thin, discontinuous rangia lens (Stratum 4 or middle midden), and a lower midden comprised almost exclusively of oyster (Stratum 5).

The test pit data suggested that “the” shell midden at the Guadalupe Bay site formed over time as overlapping debris deposits representing different occupational episodes. Although the upper shell layer seemed to vary across the site, the lower, predominantly oyster, lenses were thought to represent the same occupation. The middle rangia lens (Stratum 4) in N62 W100 was seen as the result of a short-term occupation that occurred between deposition of the lower and upper shell lenses. Assuming that the shellfish had been collected nearby, the differences in dominate shell type suggested that the local estuary environment varied through time from relatively saline conditions conducive to oysters to brackish conditions favoring rangia.

Analysis of the testing data, surface-collected artifacts and vertebrate faunal remains combined with radiocarbon dates, and seasonality studies of the rangia shells provided a provisional interpretation of site occupation through time. The Guadalupe Bay site seemed to have been initially occupied in Late Archaic times (early Aransas phase) around 700 B.C. Faunal material from this occupation, mostly comprised of oyster shells and marine fishes, indicated that the earliest occupation of the Guadalupe Bay site took place prior to development of the modern Guadalupe River delta, at a time when the site would have been located adjacent to the open waters of San Antonio Bay proper. Faunal analysis also suggested that this occupation may have occurred during the cooler months of the year and, as such, might be equivalent to the large “Group 1” winter encampments postulated by Robert Ricklis for the central Texas coast.

Late Archaic people sporadically visited the site over the course of the next five or six hundred years. One visit left behind the thin rangia lens identified as Stratum 4 in Test Unit N62 W100. The change from oyster to rangia was interpreted as the result of the Guadalupe River delta system building seaward into San Antonio Bay, providing a tremendous influx of freshwater. Occupants of the site no longer looked across the open waters of San Antonio Bay, but rather across an embryonic Guadalupe Bay towards the low-lying marshes and natural levees of the Guadalupe delta.

The next evidence of occupation came from the lower portion of the upper shell midden (Stratum 2) in Test Unit N62 W100. This deposit, composed primarily of oyster shells, included a dart point and yielded a radiocarbon date of A.D. 194 ± 88 within the late Aransas phase. The fact that oysters once again predominated the faunal assemblage, and elements of marine species made up almost half the vertebrate remains, indicated that Guadalupe River discharge had moved to another lobe away from the site and that open bay conditions once again existed.

Following this, the site was reoccupied by ceramic-producing people of the Rockport phase (ca. A.D. 1150 to 1700) of the Late Prehistoric period. This occupation was notable for the relatively large quantity of artifacts (both stone tools and pottery) and its rather large percentage of freshwater fish species and probable bison remains from both test units. An environment approaching that of today was suggested. Given the presence of the bison remains, plus several fish species indicative of warmer weather, it was theorized that the Rockport occupation may be related to a small “Group 2” warm-weather camp, as proposed by Ricklis.

The final aboriginal occupation, identified in the surface collections was related to the historic Live Oak phase marked by Spanish artifacts dating to the late 1700s. The aboriginal inhabitants of the site probably obtained these early European artifacts from the nearby mission of Nuestra Señora de Refugio, either while the Spaniards occupied the mission or after it was abandoned. It also was suggested that the occupants of the Guadalupe Bay site might have included some of the Karankawa Indians who reportedly ransacked the mission in 1794.

The final evidence of site use came in the form of the scattered whiteware sherds picked up during the surface collection. These most likely represented items discarded over the terrace edge by early European and American settlers who resided atop the Beaumont Formation near the site. Based on historical records, it is known that the first permanent settlers, including many German immigrants, moved into the region in the 1840s and 1850s.

Overall, the 1989 testing project provided enough data to support the notion that Guadalupe Bay was an extremely important site and that it was eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Yet planned improvements of the Victoria Barge Canal including widening and dredging would adversely impact the site. Accordingly, the Corps of Engineers asked that CEI prepare a “data recovery plan” targeting research questions relevant to the site that could be addressed by the excavation of an eight-percent sample of the midden area within the Corps’ ROW. This plan was the basis for a six-month-long excavation project that took place between December 1991 and May 1992.

1992 Excavations

The first order of business upon returning to Guadalupe Bay for the 1992 investigations was reestablishment of the 1989 archeological grid across that portion of the site within the Corps’ ROW. This involved using surveying equipment to run major grid lines across the site, clearing lines of sight through the dense brush along the canal, and setting out chaining pins at key points. Once alignment of the 1992 grid was established, an up-to-date and more-detailed contour map of the site area within the ROW was produced.

Following reestablishment of the site grid, a series of close-spaced auger borings was drilled with a hand-turned bucket auger at 12 of the 13 proposed 1-by-1-m sample unit locations that were spaced at 10-m intervals across the site. Overall, the auger borings extended in depth from a minimum of 110 cm to a maximum of 220 cm and proved to be extremely useful in guiding the excavations of the subsequent 1-by-1-m sample units.

Sample Units

The excavation of a systematic sample of 1-by-1-m units was designed to provide more information on the spatial distribution of the various components recognized during the 1989 testing program. The main aim was to isolate the areas of the site with both upper and lower midden zones that would be most conducive to major excavations. It was hoped that these sample units would allow for the identification of either special-activity areas related to a specific component, such as an isolated shell pocket or discrete habitation unit, or an individual camping locus composed of a structure, hearths, storage pits, and associated refuse. It also was hoped that the 1-by-1-m units would encounter a concentrated Group 2, Rockport phase component in the upper shell lens and an earlier Group 1, early Aransas phase component in the lower shell lens. Block excavations could then be opened in each of these areas.

Eleven 1-by-1-meter sample units were excavated, and combined with the two 1989 test pits, these provided relatively complete coverage of the site area within the ROW. The grid coordinates of the northeast corner of each 1-by-1-m unit served as the unit’s identifying designation. That corner also served as the datum point for the unit (with a 0-cm depth), and all depth measurements were related to it. Units were dug in natural strata, with 10-cm-thick arbitrary levels removed from within each natural stratum if the stratum was greater than 10 cm thick.

Trowels and other small hand-held tools, such as three-prong garden weeders, were the principal tools utilized during excavation. All artifacts seen by the excavator while digging, such as sherds, lithic tools, flakes, etc., were piece-plotted individually by horizontal and vertical placement within the unit, assigned specific “Field Specimen” numbers, and bagged separately. In order to recover small artifacts and bones, all excavated sediment was waterscreened through 1/4- and 1/8-inch wire mesh.

Block Excavations

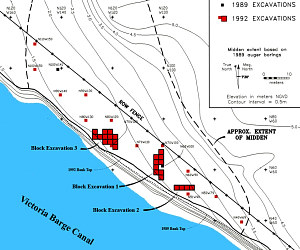

The sample unit data indicated three areas where expanded block excavations, composed of adjacent 2-by-2-meter excavation units (XUs), would be most likely to provide the greatest information for the amount of excavation effort involved. Excavation of the 2-by-2-m units followed the same methodology as employed during the digging of the 1-by-1-m units.

Block 1 consisted of nine units and targeted an area of the site where an oyster lens appeared to abut against a thin rangia lens. It was hoped that information regarding different subsistence patterns might be obtained by comparing the contents of the two lenses. Block 2 was composed of four units that had the potential of recovering remains related to a Contact period component at the site. Several potentially early historic (Spanish mission period) artifacts had been recovered in a nearby 1-by-1-m unit. Block 3, consisting of 12 units, was located between N68 and N76 and W118 and W128. It was placed in an area where the testing encountered the greatest quantity of Rockport phase material, and where a deeply buried, presumably Late Archaic oyster lens was situated relatively close to the surface and could be examined without having to remove a tremendous amount of soil.

Block 1: exposed most of a 4-by-12-m area that stretched north-south between the ROW fence and the barge canal bankline. Since the main excavation goal in this area was to explore potential differences in subsistence strategies, as reflected in the faunal remains from the rangia and oyster lenses present in the upper strata, excavation was halted above the underlying noncultural deposit and the deeper rangia and oyster deposits of likely Archaic age. The excavations encountered both Late Prehistoric and Late Archaic remains in the upper strata of these units. Generally, the Late Prehistoric material occurred within a scattered layer of rangia and oyster shell, identified as Stratum 2, while Late Archaic remains were found in the more intact, underlying rangia and oyster lenses.

Block 2: covered a 2-by-8-m area that extended in an east-west direction near the bank along the canal. The area was positioned immediately north of the sample unit at N51W90 in hopes of gaining a better sample of the late-eighteenth-century aboriginal component hinted at in the recovery from that unit. Therefore excavations were terminated at the base of the upper shell midden. As with Block 1, neither the underlying colluvium/alluvium nor the deep Archaic shell deposits were excavated.

Block 3: The third block excavation consisted of an irregularly shaped set of 12 contiguous units designed to expose a large portion of the Late Prehistoric midden in an area containing a wealth of artifacts. Once again, most of the units in Block 3 only removed the upper aboriginal shell midden(s), and excavation ended when the top of the noncultural colluvium/alluvium was encountered. However, in an effort to gain some information on the deeper Archaic deposits, two of the units in Block 3 were taken all the way down to the preoccupation surface. These deep units sampled several shell lenses of Archaic midden and exposed some of the more interesting remains uncovered during the investigations. With the advantage of hindsight, it is unfortunate that more time was not allocated to the excavation of these deeper deposits. However, the majority of the research questions developed for the Guadalupe Bay data-recovery plan concerned the Late Prehistoric and Contact period occupations, and the intriguing deep Archaic data from Block 3 were not encountered until near the very end of the fieldwork. |

Profile of 1967 test pit excavated by Cecil Calhoun showing two distinct shell midden layers separated by a culturally sterile layer of sand. Adapted from Weinstein 1992, Figure 3-1.

|

Aerial photo mosaic dating to the early 1960s showing the Victoria Barge Canal being excavated through the peninsula of Beaumont Formation located immediately south of Green Lake. Note the fresh spoil deposits lining both sides of the canal and the dragline in operation at the northeastern end of the canal cut. This cut has yet to reach State Highway 35 where today a highway bridge spans the canal. Enlarge to see details.

|

Initial auger boring in 1989 to probe the depth of the cultural deposits and the extent of the shell midden. TARL Archives.

|

1989 map of site showing site extent and test locations. CEI graphic.  |

Crew member removes one of a succession of "plugs" from each auger hole and records the depth that distinctive deposits are encountered. TARL Archives.

|

Cross sections based on 1989 augering showing how shell midden deposits (gray) abutted against and draped over the Pleistocene (Beaumont Formation) bluff. Refer to 1989 site map for locations of cross sections. Adapted from Weinstein 1992 Figures 3.3 and 3.4.  |

Guadalupe Bay site map based on 1992 investigations. CEI graphic.  |

Eleven test units measuring 1-x-1-meter were excavated during the early part of the 1992 investigations to pin-down the areas of the site most conducive to block excavations. TARL Archives.  |

Crew member monitors the water pump used for waterscreening. Keeping the pump running and preventing it from being inundated by the wakes created by passing barges required constant attention. Solving basic logistical challenges are an essential part of any archeological dig. TARL Archives.  |

Waterscreening operation at the Guadalupe Bay site. By gently spraying sediment through nested ¼-inch and 1/8-inch-mesh screens, thousands of small and fragile artifacts and animal bones were collected. On calm, warm days waterscreeners went merrily about the business, but windy, cold days were quite another story. The plastic sheets seen here were used to direct the returning water back into the barge canal without causing further bankline erosioin, as well as to reduce the amount of cold spray on lower limbs. TARL Archives.  |

Block 1 excavations in progress. By excavating alternating units, the wall profiles from completed units helped guide the stratigraphic excavations. TARL Archives.  |

Beginning excavations in Block 3. TARL Archives.  |

Continuing excavations in Block 3. TARL Archives.

|

Another view of the Block 3 excavation, The area's stratigraphy is revealed the walls of the completed 2-x-2-meter unit in the center of the photograph. Clearly visible is the thick layer of Late Archaic oyster shell (Stratum 7). TARL Archives . |

|