A New Interpretation of Features |

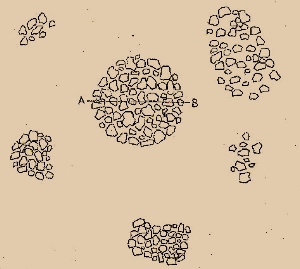

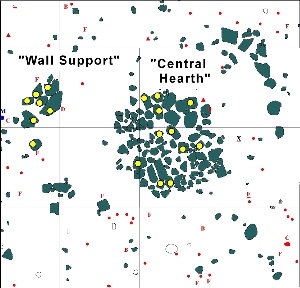

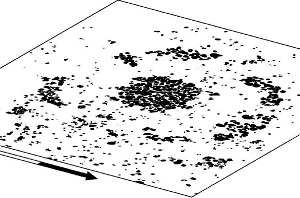

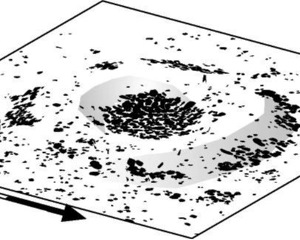

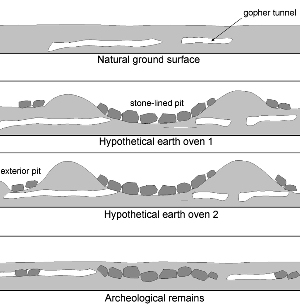

The Graham-Applegate Rancheria exhibit was written in 2001 while fieldwork was still in progress; since that time, our interpretation of the circular stone features has radically changed. Initially thought to be the remains of hut-like houses based on earlier interpretations of similar circular features found in the Lake Buchanan area, by the last year of fieldwork we began to see the stone circles as baking pits (also known as earth ovens), a rather common feature at prehistoric sites across central Texas (see the Honey Creek, Camp Bowie exhibits on TBH, also, “Cooking with Granite” in this exhibit). Obviously baking pits in no way resemble houses, so how was there ever any confusion? The following paragraphs will attempt to explain the process of this reinterpretation. Soon after Curtis Tunnell of the Texas Memorial Museum first saw the circular features on the Lake Buchanan shoreline in 1962, he wrote a short article in the museum newsletter referring to them as an archeological “mystery.” His best explanation was that each feature represented a peculiar arrangement of stone hearths but grouped so close together that they would burn anyone who sat near them. A short time later, he took UT professor E. Mott Davis to see them. To Davis, the features resembled archeological examples of house floors with a central hearth surrounded by wall remains. He was aware of the small living space within these would-be structures and speculated that the circles might be sweat lodges. Both archeologists saw the same features but came up with totally different interpretations. Archeologists often encounter objects from the past that defy easy explanation. This is not only because the archeological record is usually incomplete because of the impacts of decay and destruction over time, but also because archeologists are often investigating cultures radically different than their own, belonging to people who behaved and thought quite differently than we do. Interpreting the archeological record — to translate it into past human behavior and actions—is a critical part of archeology. With knowledge of what people were doing in the past, larger theoretical questions, such as the adoption of agriculture for example, can then be addressed. Just knowing what the circular features were used for, whether as houses or earth ovens, would be interesting but at the same time trivial. We already are fairly certain that some sort of dwelling was used at most occupation sites, and ovens are commonly reported at prehistoric sites in central Texas. But if the Graham/Applegate circular features are revealed to be earth ovens, then they might be able to tell us about subsistence practices and ultimately why hunting and gathering persisted in central Texas long after adjacent regions turned to agriculture. Conversely, if they are houses we might be able to make meaningful statements about household size, band size, and other aspect of social organization within the context of a small Late Prehistoric encampment. Archeologist and philosopher Alison Wylie has pointed out that most archeological interpretation is based on analogical reasoning. This basically means that a researcher will look for similarities between the archeological remains and some known examples from his or her experience that can be used to understand and “fill out” the archeological record. Using analogies is how we make sense of our world; we would otherwise be in a constant state of bewilderment not recognizing anything around us. Both Tunnell and Davis were using analogies to explain the stone circles they saw on the Lake Buchanan shoreline, but they came up with different interpretations; Curtis saw a group of hearths and Davis a house or sweat lodge. They cannot be both right, and one problem with analogical reasoning— comparing the past with the present—is that multiple interpretations are often possible. Many archeologists beginning in the 1960s and even earlier rejected the use of analogies to understand the past because this type of reasoning is often unreliable and known to lead to false conclusions. It was the selection of only positive analogies that led to the house interpretation. The circular features do in fact look like house floors seen both archeologically and ethnographically across the world, with a central hearth surrounded by what looks like traces of wall foundations. It just so happens that all reported examples in central Texas fall within the size range for hunter-gatherer houses, and the circular outline of the house is typical for mobile hunter-gatherers. But there are also negative analogies. Davis immediately saw that the central hearth was disproportionately large for the size of the house, hence his sweat lodge hypothesis. Sometimes negative analogies can be explained away. Archeologist Lee Johnson, in writing up the report on the Lion Creek site where similar stone circles were uncovered in the 1970s, made an analogy between the Lion Creek central hearths and the hearths in Anglo-Saxon houses, which constitute more of a stone platform or work table with a small fire in the center. The relevance of such an analogy can be questioned since the Anglo-Saxon environment and economy were very different from those of the central Texas Late Prehistoric, but Johnson’s interpretation does offer a way out of the problem of the disproportionally large hearth. If Johnson’s interpretation for the central hearths is correct, then we would expect only the central area of the hearth to show signs of fire exposure. Visually, the surfaces of the Graham-Applegate hearths appear uniform with no obvious charcoal staining or other signs of fire. To find supporting evidence for Johnson’s “workbench” hypothesis, we asked University of Texas geologist Wulf Gose to analyze the magnetic properties of the rocks in three of the circular feature hearths. This analysis can reveal if a burned rock remained in place after its last heating, and often the maximum temperature the rock was heated to. If Johnson’s hypothesis is correct, then we’d expect the rocks along the periphery of the central hearth – the area used as a workbench - to have been exposed to much lower temperatures than the rocks in the center of the pavement where a fire would have been burning. Gose for the most part found that all the tested rocks in the hearths had been heated to red-hot temperatures of over 500 degrees Celsius (930 degrees F), and that they’d remained mostly in place since then. These are temperatures we would expect for rocks used in earth ovens, not inside huts covered with flammable materials. Another negative aspect that’s more difficult to explain is the presence of small features at Graham-Applegate with the same basic pattern as the large circular features. For example, Feature 56 has a central hearth and is surrounded by satellite clusters, but the entire feature is only 190 cm (6 feet 3 inches) across. A bit too small to be a house, it otherwise resembles the larger features. So far, it appears that the Graham-Applegate circular features have more in common with oven-type features than aboriginal houses. If the central hearths lacked satellite rock clusters, then there would be no question that they are, as archeologist Steve Black would say, heating elements of a earth oven (see Honey Creek exhibit). So what are the satellite clusters? Could they have actually been used somehow to stabilize house walls or are they something else entirely? The relevance of the wall support aspect of the analogy can also be called into question. At Lion Creek, Johnson speculated that the satellite clusters were used to help stabilize wall posts in the loose, sandy soil. At Turkey Creek Ranch in Concho County, another site with a similar circular feature, the investigators could see open spaces within the satellite clusters where they speculated wall posts could have gone. In this instance, the rocks appear to have been stacked on the surface around the posts to provide support. The spaces measured from 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 inches) across, indicating the post diameter. If this interpretation is correct, the largest of the inferred posts would probably weigh more than the rocks supporting it, and in any case all inferred posts would be so heavy that no supporting rocks would be necessary, especially with the added weight of the material—hide, mat, or grass— used to cover the hut. Ethnographically, rocks where more often used to hold down the covering to keep it from flapping in the wind and to keep cold air from entering the base of the structure. The rocks were usually large and heavy enough to do the job, but at Graham-Applegate the rocks making up the wall supports are for the most part small. For the circular feature we were calling House 1, the average weight of a satellite rock is 430 grams (less than one pound). Piled up in fairly large numbers, such rocks could work in holding down the covering, but it would still make more sense to use fewer, heavier rocks. Large rocks are readily available in the Graham-Applegate area. Once uncovered, we could see that many of the wall support rocks had fractured as if by heat. This was borne out by Gose’s analysis of the magnetism in a sample of the “wall supports” rocks of “House 2” that showed they had been subjected to high heat. His analysis also indicated that the rocks had been heated repeatedly in different positions. Gose sampled mainly the larger wall support rocks, but many rocks in these satellite clusters are small and of a size similar to rocks found in the burned rock middens. Midden rocks are now generally accepted to be cleanouts of heat-fractured rocks from earth ovens. Taking into account the complex heating history of the rocks in the satellite clusters and their high temperatures and fracturing, they resemble oven cleanouts more than rocks that would be used to support hut walls. What we seem have then in these satellite clusters is the beginning of burned rock middens, but such an interpretation is actually nothing new. Nearly forty years ago, Texas Highway archeologists uncovered satellite rock clusters around certain baking pits in Musk Hog Canyon in Crockett County, which Clive Luke interpreted as the “outcasts from a previous use of the central pit/hearth.” In this case, there was virtually no rock-free space between the oven and satellite clusters, so there was little resemblance to house floors. We still need to explain why the cleanout piles—what we were calling wall supports—are distributed more or less evenly around the oven with a rock-free space in between. At the Honey Creek site, cleanout piles were identified spread out to one side of the oven pit, which would seem an easier way to go about depositing waste rocks. However, observations made by archeologist Lewis Binford about how people, and hunter-gatherers in particular, organize their workspace offers an explanation for this pattern. Binford spent much of his mid career in what he called “actualistic” studies, living with hunter-gatherers and documenting the types of trash they left behind during specific activities. He was particularly interested in the patterns this trash left on the ground. These patterns, he felt, could be used to help “translate” similar patterns seen at archeological sites into past human behavior. Binford argued that many activities conducted by totally different societies produce the same basic trash patterns because human behavior is in certain ways constrained by their anatomy. His approach has been criticized by other archeologists, especially Ian Hodder, who emphasizes context and the influence of cultural and social attitudes in forming the archeological record. But one particular idea of Binford’s concerning artifact patterns that result from human activities performed while standing, as opposed to sitting, may help explain the ring of rock clusters surrounding oven features (see McKinney Roughs exhibit for an example of artifact patterns resulting from activities performed while sitting). Binford noted a regularity in the pattern in debris which resulted from work activities that where conducted while standing, which he referred to as the “classic feature-centered pattern.” The center area would be the focus of the activity—Binford’s actualistic observations included an Australian Aborigine roasting pit and a Ninamuit Eskimo caribou carcass—surrounded by an empty space so workers could walk around the task area. Beyond this open area would be an outer zone where material was discarded and out of the way. A similar pattern can be seen in the circular features at Graham-Applegate: the central work area is the earth oven, with an open space around for workers to walk around it and an outer zone of discarded rocks. Of course as was mentioned earlier, the people could just as well have tossed the rocks to one side, and earth oven experiments conducted by archeologists don’t necessarily produce this circular pattern of waste material, but people who have to cook in earth ovens on a regular basis would tend to do it in the most economical fashion, as Binford observed, especially if they planned to reuse the oven pit. But there could be more to this empty space than just an open path around a task area. The rock-free space around the oven may also have had another purpose: to store the dirt needed to seal in the heat and moisture once cooking commences. A lot of dirt is needed to create this seal, and if inadequate, could result in the food being burned after all moisture escapes. The pattern of rocks seen in the outer ring of “House 1” at Graham-Applegate could result from rocks discarded on the outer slope of a circular berm or mound of earth. Such a berm would form when the earth seal is scraped away from the oven to the outer margins to expose the cooked food. A berm would be difficult to discern during conventional archeological excavation, but at least one example of an earth oven with a possible berm has been recorded. On Double Horn Creek in Burnet County, the creek channel has bisected an earth oven buried in terrace sediments, providing a near-perfect cross-section of the feature. The profile shows a concave pit outlined by rocks and charcoal, and, importantly, with what appears to be mounded earth taking the form of lighter-colored sediments outside the pit. We can speculate that the Graham-Applegate circular features once resembled the Double Horn oven, being shallow pits lined with rocks and charred wood. Because of the environmental conditions at Graham-Applegate, over time these features have transformed into nearly flat rock pavements with only traces of their organic materials remaining. Much data were collected during the Graham-Applegate excavations, and only a small amount is presented here. There is no way to definitely say that the circular features are not houses—that kind of certainty is usually not found in archeology—or that these features represent only one thing. It’s possible that the same basic pattern could have been produced by very different activities and behaviors, but the oven hypothesis does seem the most plausible, and viewing these features as ovens allows us to ask a whole new set of questions dealing with burned rock midden formation.

|

|