Ancient Houses of Central Texas |

|||||||||||||||||||||

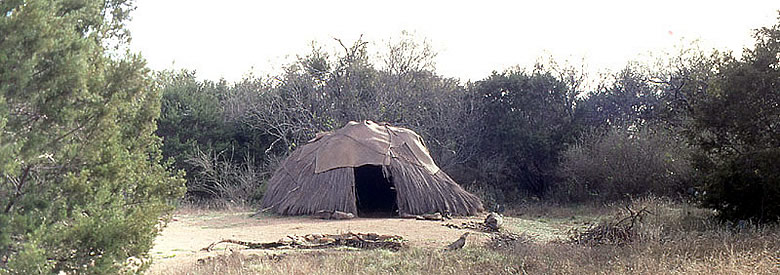

Reconstructed hut at the Nightengale Archeological

Center, believed to resemble in size and form the dwellings of prehistoric

Texans. Photo by Milton Bell.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

For many decades, archeologists were pessimistic about ever finding remains of prehistoric houses in central Texas. The mobile bands of hunter-gatherers who lived in this part of the state were thought to have constructed very flimsy huts or skin-covered tents that would leave little trace for archeologists to find, especially after hundreds or thousands of years. This changed in the early 1960s when unusual stone circles were discovered eroding out of the sandy shoreline of Lake Buchanan, a large artificial reservoir 60 miles northwest of Austin. There was speculation at the time that these stone circles were the remains of ancient structures, although other explanations also were proposed. Some thought they might be the remains of specialized cooking facilities. Excavations of similar circles at the Lion Creek site in Burnet County in the mid 1970s and the Turkey Bend Ranch site in Concho County in the late 1980s provided additional evidence that these features were probably the foundations of houses built by Archaic and Late Prehistoric peoples. At the Graham-Applegate site, the remains of what were tentatively identified as five houses were excavated, and these are very similar to the stone circles discovered earlier elsewhere. In this section, we explore some of the evidence that initially led us to believe these remains were houses. This interpretation has since changed (see A New Interpretation of Features in this exhibit). Elements of a House?As at the other sites, all that has survived of these features are a central stone pavement where the hearth fires may have burned and a ring of stone clusters surrounding this pavement that may have helped support the walls. Exactly how the outer ring of stones of these possible houses supported the walls is unclear. Some stones may have been used to hold down the hides or whatever material was covering the structures, while others braced the bases of the thin saplings that are believed to have supported the walls. At the Graham-Applegate site, we thought the stones likely were used primarily for the latter reason, that is, to stabilize the posts in the loose, gravelly soils around the site. While no traces of post holes (or woodpost stains) can be seen in the soil, the elevation of these rocks in relationship to the floor surface indicates that, in most cases, the posts were placed in shallow holes dug by the aboriginal builders. The rocks would have been placed around the base to prevent the posts from shifting or coming out of the ground during strong winds. It is also possible that a shallow trench was dug completely around the wall area, in part to create a trap for rain water, but also for the wall posts. If these indeed were houses, we can only speculate as to what the superstructure may have looked like based on materials and technologies available to the people during the Late Prehistoric. The brief descriptions left by early explorers of North America and the more-detailed descriptions of recent houses built by people with a similar level of technology also aid us in reconstructing the rancheria houses. Most likely a dome-like frame was constructed by arranging a ring of green sapling posts upright in the ground, and then bending upper ends inward and tying them together. Small branches would then be attached horizontally to these posts to form a framework to support the covering. Many covering materials would have been available, and early Spanish accounts of Indian houses in what is now south Texas mention grass, woven mats, and animal hides.

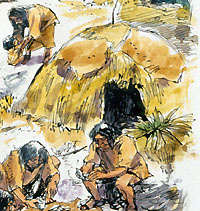

Interior of prehistoric dwelling as visualized

by artist Peggy Maceo. Image courtesy of the Lower Colorado River

Authority.

There was a curious aspect to these possible houses that set them apart from other known hunter-gatherer dwellings. Much of the interior space was devoted to a large, central paved area or hearth, leaving only a relatively narrow (a meter or less) ring of living area between the hearth and walls (note the spatial arrangement in the artist's scene of hut interior). With some of the "houses," it is possible that the living space extended onto the stone pavement, while in others the pavement seems to have been raised somewhat above the floor. One theory is that the pavement served as a "work bench" of sorts, where tasks could be performed above or away from the floor and close to the fire for light and warmth. For obvious reasons, a large fire would not have been built on these hearths inside a thatch-covered structure, and the archeological evidence supports this. Very little charcoal staining was noted in the hearth fill of "House 1"—fires were built there but not intense ones such as those in the earth oven. Some Indian groups in the American West would heat rocks outside their dwellings and then bring the hot stones inside for heating without the hazards of smoke and flames. The presence of these large central hearths has led to speculation that this type of structure was used as a sweat lodge, but evidence from Graham-Applegate seemed to support the view that these were places where people lived and carried out domestic activities. Several of these structures are in very close proximity to one another, which would be unusual for sweat lodges. Three of the structures have small hearths outside their walls, along with food remains, more in keeping with a small hut-like dwelling where cooking was done outdoors whenever possible. The Graham-Applegate "Houses"The feature originally identified as House 1 is the largest and the best preserved

of the five presumed houses excavated at Graham-Applegate. The rocks

used to stabilize the walls (wall

supports) form a nearly complete and well-defined ring. The

large gap in this ring on the south side is a clear indication that

the doorway faced in that direction, away from the prevailing winds

of winter cold fronts or "northers." The diameter of the

entire structure is 4.25 m (14.2 ft) and has a floor area (including

central hearth) of around 12.5 square meters. A large stone pavement

or central

hearth covers the middle of the floor area. It provided a platform

for the small fires that would have warmed the house and perhaps also served

as low table or work bench. A cross-section of the hearth reveals

that a shallow basin was first dug and then filled with stones of

different sizes to create a level surface. This presumed house also contains

many more artifacts both on the floor area and outside it than the

other "houses" and has at least five small cooking hearths outside

its walls. The clutter about this structure might mean it was occupied

(and perhaps reoccupied and rebuilt) over a long period, allowing

more refuse to build up around it. Or perhaps "House 1"—with

its larger size and close proximity to the communal earth oven—was

the focal point for activities of the entire rancheria.

A singular pile of quartz rocks two meters long connects "Houses 3 and 4," stacked there by the rancheria folk for some unknown purpose. Quartz was not a very useful rock for these people. It tends to break rapidly into many small, sharp shards when exposed to heat, making it a poor choice for cooking stones. Unlike quartz crystal, the quartz found around the site area does not flake well and this rock was rarely used to make chipped stone tools. Perhaps they were stacking the stone there simply to get it out of the way. Given the rarity of prehistoric structural features in the archeological record, it is important to consider all possibilities during investigations. In this case, initial interpretations were disproved by evidence gleaned in later technical studies, discussed in the New Interpretations section.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||