Fatty Acid Analysis

Fatty acid analysis provides a means of broadly identifying organic residues remaining on cooking or food processing materials used in the past. Identification is most successful on a general scale, eg., plant vs. animal, rather than attempting to distinguish specific species. Fatty acids are the major constituents of fats and oils (lipids) and occur in nature as triglycerides, which consist of three fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule by ester linkages. Fatty acids are insoluble in water and relatively abundant compared to other classes of lipids, such as sterols and waxes, making fatty acids suitable for residue analysis. The composition of uncooked plants and animals provides important information toward determining what people cooked, but it is not possible to directly compare modern uncooked plants and animals with highly degraded archeological residues. That is because many of the fatty acids degrade or change composition over time. Unsaturated fatty acids, which are found widely in fish and plants, decompose more readily than saturated fatty acids, sterols, or waxes. In the course of decomposition, simple additional reactions might occur at points of unsaturation, or peroxidation might lead to the formation of a variety of volatile and non-volatile products that continue to degrade. Peroxidation occurs most readily in fatty acids with more than one point of unsaturation.

Continued work has resulted in further understanding of the decomposition patterns of various foods and food combinations. The results of these decomposition studies enabled refinement of the identification criteria. Rocks that were used for cooking plants and animals in the form of boiling stones, for example, should have food residues on them that are retrievable and identifiable. Burned rocks from hearths and pit ovens are also likely candidates.

Previous research has demonstrated that organic residues can be extracted from burned rocks used by prehistoric peoples to process foodstuffs and generally identified to groups of plants and animals. This proxy line of investigation is critical when environmental conditions are not conducive to the preservation of primary organic data, such as plant parts, seeds, nuts (macrobotanical remains), and faunal materials.

Methods

A total of 102 samples from the Varga Site including eight pottery sherds and 94 burned limestone rocks, were submitted to Mary Malainey of Brandon University for analysis. The analytical procedures included multiple steps. Possible contaminants were removed by grinding off exterior surfaces with a Dremel® tool fitted with a silicon carbide bit. Immediately thereafter, each sample was crushed with a hammer mortar and pestle and the powder was transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask. Lipids were extracted using previously developed methods. The powdered sample was mixed with a 2:1 mixture, by volume, of chloroform and methanol using ultrasonication (the application of ultrasound energy). Solids were removed by filtering the solvent mixture into a separatory funnel. The lipid/solvent filtrate was washed with double-distilled water. Once separation into two phases was complete, the lower chloroform-lipid phase was transferred to a round-bottomed flask and the chloroform was removed by rotary evaporation. Any remaining water was removed by evaporation with benzene. Chloroform-methanol was used to transfer the dry total lipid extract to a screw-top glass vial with a Teflon®-lined cap. The sample was flushed with nitrogen and stored in a -20°C freezer. Read more.

It must be understood that the identifications given do not necessarily mean that those particular foods were actually prepared because different foods of similar fatty acid composition and lipid content would produce similar residues. It is possible only to say that the material of origin for the residue was similar in composition to the food(s) indicated.

Findings from Fatty Acid Analyses

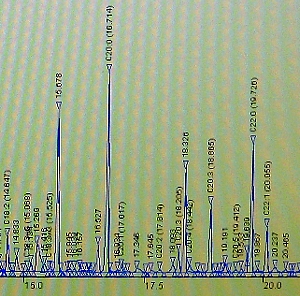

The overall results are quite variable, with a high percentage of samples revealing plants were being cooked in all time periods. Only one sample yielded insufficient fatty acids to attempt identification. Fatty acid recoveries were very low in five other samples. Some 14 residues have significantly elevated levels of C18:1 isomers, which indicates the presence of fat or oil in the residue. These levels were observed in the decomposed residues of foods of very-high-fat-content seeds or nuts, such as piñon. Rendered fats of certain mammals (other than large herbivores) exhibit similarly very high levels of fat content. All 14 residues probably represent the residues of plant foods.

A total of 23 residues are characterized by high levels of C18:1 isomers. Twenty-one have levels of C18:2 above five percent, which indicates that they are of plant origin. The most probable sources of these residues are locally available high-fat-content seeds and nuts. Two other residues have high levels of C18:1 isomers but levels of C18:2 are low. The origin of these two residues is ambiguous (possibly animal).

Eleven residues fall on the border between moderate-high- and high-fat-content foods, and all are likely to be of plant origin. Twenty-four residues are typical of foods of moderate-high fat content with 17 having strong indications of a plant origin while the remaining seven samples, a plant origin is slightly favored. Nine residues fall on the border between medium- and moderate-high-fat-content foods. On the basis of their elevated levels of C18:2, eight residues are probably of plant origin.

Nine samples have elevated levels of C18:0, which occurs in residues produced from large herbivore meat. Another eight were probably a mixture of plants and animals. One residue was consistent with large herbivore prepared with plant or bone marrow.

For the Toyah component the lipid residue analyses is summarized as follows. The interpretations from the lipid residue analyses on the burned rocks imply that only about 27 percent of the 29 individual samples indicated large herbivore meat, and 57 percent of those could actually represent plant signatures. The 27 percent figure for meat residue seems quite low when one considers the relatively high frequency of bone recovered. This low percentage in the lipid residues reflects how the meat, marrow, etc. from the animals was processed. It may be that most of the meat, marrow, etc. was consumed raw or dried and not cooked by hot rocks. Many ethnographic and historic accounts indicate that peoples ate meat without cooking it. Certainly there are other means of cooking meat without the direct use of hot rocks. In contrast few plants can be directly consumed without cooking (seeds, nuts, and berries being exceptions), and this is reflected in the lipid residue analyses. Most burned rocks yielded quantities of moderate to high fat residues interpreted as representing from plants; medium to borderline medium fat content is present in about 21 percent of the burned rocks, whereas the rest have higher fat content.

In two instances, a burned rock scatter (Features 8 and 25) was next to an in situ heating element/hearth (Features 9 and 38) in Block B. In each case, these apparently paired features (Features 8 and 9, and Features 25 and 38) contained some burned rocks, which yielded residues that were interpreted as indicating large herbivore meat. The latter meat interpreted residues were the only ones identified from Block B. No identified Toyah features in Block A yielded burned rocks with residues interpreted as representing large herbivores. This horizontal difference may signal specific activity localities, or possibly different activities in different occupational episodes.

The lipid residue analysis on six sherds from the Toyah component, two each from Vessel Groups 1, 2, and 3, reveals results similar to that discovered on the burned rocks. The detected residue signatures were interpreted as ranging from borderline moderate-to-high and high fat content, implying that fatty plant parts were cooked in these vessels. These results, combined with the stable carbon isotope values that range from -24.3 to -27.6‰ and nitrogen isotope values that range from -2.6 to 6.9‰ imply that some plants cooked in these vessels were probably legumes such as mesquite beans, whereas in one case the nitrogen isotope value (6.9‰) supports a plant that is in the range of huisache bean. The detected carbon isotope values of -27.2‰, plus the nitrogen isotope value of 6.9‰, are very close to the carbon isotope value of -27.3‰ and nitrogen value of 6.2 and 7.5‰ derived from modern huisache bean meat from Maverick County, Texas. The products cooked in the vessels appear to reflect fatty plants rather than animals, even though a relatively large and fragmented bone assemblage was recovered from this Toyah component.

In the Late Archaic period, the large herbivore meat is only reflected by about three percent of the 33 burned rock samples analyzed (i.e., in one sample). The Middle and Early Archaic components did not reveal any lipid residues that reflect cooking of large herbivore meat. Extensive cooking of plants is implied from the lipid residues, providing a sharp contrast to the direct evidence reflected in the faunal-bone assemblages. In combination, the two different data sets reflect a more comprehensive and broader range of resources exploited by the groups rather than does either taken alone.

The fatty acid analyses have provided important information concerning what general resources— plants or animals—were being cooked by the burned rocks and in the pottery vessels. These insights to the past provide information to the actual processing of food resources that was not previously known.

|

Fatty acid analysis is critical when primary organic evidence, such as macrobotanical (plant) and faunal (animal) remains, are not well preserved. This analysis addresses questions such as:

|

|

|