Earliest Peoples

Today the topic of the earliest peoples of the Western Hemisphere is the subject of sometimes heated debate among archeologists, and shows no sign of letting up! New data and new claims appear with increasing frequency, but most of the real academic debate is framed in arguments that are quite technical and complex. The hottest debate, centers on the arrival of the earliest peoples, both when they arrive, was it 40,000 years ago or 14,000 years ago? As well as their origins, did all New World peoples really come across the Bering Strait, or did some make it here from Japan, or even Western Europe? For better or worse, little of this debate has been based on evidence from the South Texas Plains.

The earliest known human culture in the region is represented by Clovis peoples who entered the region by about 11,500 B.C. There is no credible candidate for a “pre-Clovis” occupation in southern Texas. Claims have been made for such antiquity at a few locales, but none of these present a useful argument. For instance, so-called crudely chipped stone tools from fossil beds in Duval County have been shown to be geofacts – flint shaped by natural processes, not humans. To be sure, Pleistocene fauna has been found in the region, especially secondary deposits of mammoth bones and teeth, but, as in the case at Palo Blanco in Kenedy County, there is no evidence of associated artifacts that could suggest a pre-Clovis human presence.

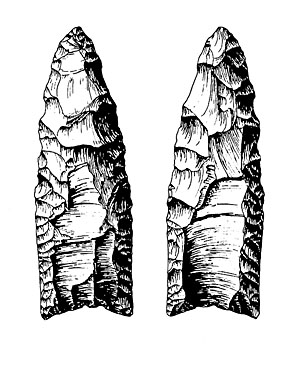

The South Texas Plains region is not, however, free from controversy over the typologies applied to the early projectile points, the most identifiable hallmarks of the widely accepted early human cultures in North America. While the fluted points characteristic of Early Paleoindian peoples (Clovis and Folsom) are relatively easily distinguished, the diverse lanceolate forms of later Paleoindian times have generated much typological debate and no small amount of confusion. The many proposed types and the apparent typological overlap between these types are enough to give the would-be classifier a pounding headache. But back to Clovis.

Based on North American studies, we assume that Clovis groups hunted late Ice Age wooly mammoths and other now-extinct megafauna in the region as they roamed a landscape that was quite different from that of today. The climate was much cooler and wetter, the Gulf coastline was much farther out (lower sea level), soils were deeper and less eroded, grasslands were thicker, there were more streamside woodlands, and more permanent streams. Collectively, these conditions supported plants and animals that can be found no longer in the region today, although most of the modern species were already present.

Recent data from sites elsewhere in Texas and North America suggest that lifestyle of Clovis peoples, long characterized as “big game hunters,” was not so one-dimensional. It is looking more and more like these early peoples were hunter-gatherers whose basic lifestyle shared much in common with that of later Archaic peoples. Conventional North American culture history suggests that Clovis was followed by Folsom, perhaps around 10,800 B.C. While some Folsom groups appear to have targeted the straight-horned Ice Age buffalo, it is now currently believed that they too had a much broader strategy for obtaining food.

Were the Folsom peoples direct ancestors of Clovis, and did later Paleoindian cultures in southern Texas descend from them? We have no idea, or at least no solid archeological evidence. All we can say is that the South Texas Plains yields evidence of late Pleistocene “early” Paleoindians—in the form of Clovis, Folsom, and Plainview points, as well as examples of many styles of “late” Paleoindian points (ca. 9500 B.C. – 6800 B.C.)—including St. Mary’s Hall, Wilson, Golondrina, Scottsbluff, and Angostura. It is clear, however, that the Late Paleoindian peoples were exploiting an early Holocene environment, that the hunting of Pleistocene megafauna was no more. At some nearby localities, such as Baker Cave along the lower Devils River just beyond the northwest edge of the South Texas Plains, human predators caused many species of snakes and other small critters to fear for their lives.

Our understanding of the earliest human occupations in the South Texas Plains relies very heavily on data obtained from research in adjacent regions. While many sites in the region have yielded Paleoindian projectile points, only a few specimens have come from excavations. Fortunately, many Paleoindian projectile points from the surface of south Texas sites can be linked to types, and sometimes typologically linked and cross-dated by comparison with data from sites in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands including Baker Cave, Devil’s Mouth and Bonfire Shelter; sites in the Balcones Canyonlands including Kincaid Shelter, Pavo Real, and St. Mary’s Hall; and sites in the northern part of the greater Edwards Plateau including Wilson-Leonard and Gault.

There are sites in the South Texas Plains with buried Paleoindian deposits, especially those in the Guadalupe drainage system. The best known examples are in Victoria County and most are only known from collections of artifacts that have eroded from deep exposures, such as river bluffs. One example is the Johnston Heller site, 41VT15, which has yielded Clovis, Golondrina, Plainview, and bifacial Clear Fork tools). None of these sites have had major excavations. Test pits have yielded tantalizing clues, such as a Golondrina point from a deep test pit at the Willeke site, 41VT16. Other sites with buried Paleoindian artifacts have been found to have sandy soils with evidence of chronological mixing (old with younger artifacts), such as the J-2 Ranch site. See Guadalupe Terrace Sites.

Mounting a major excavation in deep alluvial terrace deposits is a time-consuming and logistically daunting proposition, nevertheless, researchers continue to try and tackle the challenge. When Paleoindian materials eroded from 41VT112 along the Guadalupe River within the city of Victoria, large-scale excavations and geomorphological studies were carried out in 1995. Unfortunately, this research demonstrated that the early deposits had been wholly washed away. Not far upstream, continuing excavation at the McNeil site, 41VT141, shows promise of yielding buried stratified Paleoindian deposits.

An excavated site whose earliest materials fall within Paleoindian times is Berger Bluff (41GD30) in Goliad County. Excavations and analysis by Dr. Kenneth M. Brown indicate that the earliest materials are primarily small fauna associated with a hearth, and that the locality may represent a foraging camp used by women and children around 9500 years ago. Aside from a triangular biface, there were no formal lithics. See Berger Bluff.

Berclair Terrace (also known as Buckner Ranch) along the Bee-Goliad County boundary has yielded a number of Paleoindian points, and it is quite likely that these were associated with the late Pleistocene fauna excavated there by E. H. Sellards and Glen L. Evans of the Texas Memorial Museum in the mid-1930s. Of particular interest are several stemmed dart points found there that were once assumed to be styles that dated to the Archaic era, but are now known to have been made during Paleoindian times. Berclair Terrace also yielded the base of a Clovis point, the distal tip of a Midland point, a section of a Scottsbluff point, and a possible Angostura point. See Buckner Ranch.

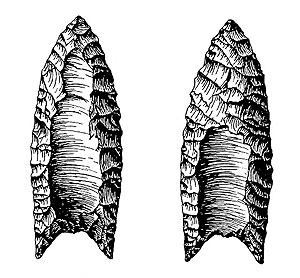

Clovis points are widely distributed across the South Texas Plains, and along the lower Rio Grande in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. They are usually found as single examples at eroded surface sites, or as isolated finds. Examples include the Nockenut Clovis point from Wilson County and an unfinished Clovis point from Atascosa County. The points are usually found on high terraces overlooking present-day stream valleys.

Clovis points are occasionally found along the South Texas Gulf Coast, which in Clovis times was perhaps 30-50 miles west of the modern beach line. One heavily beach-rolled Clovis point found near Port Lavaca is made of obsidian. Its volcanic source has not yet been identified, but it wasn't in Texas. An obsidian Clovis point base from Kincaid Shelter, on the northern edge of the South Texas Plains, has been sourced to Queretaro, Mexico. The obsidian points constitute conclusive evidence of long-distance trade and travel. Indeed, Clovis points are part of a far-reaching, technologically-similar, fluted point tradition that extends into Mexico, Belize, and other parts of Central America. See Distant Connections.

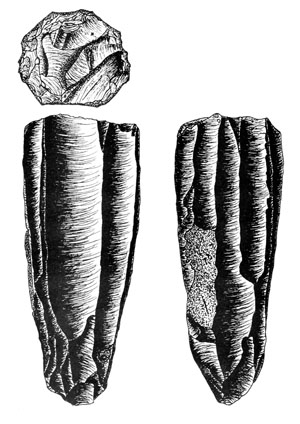

To date, the distinctive polyhedral blade cores of Clovis age, a tool-making form that is well documented at the Gault site and elsewhere, have not been documented in most of the region. Examples are known from along the Balcones Escarpment in northern Bexar County, from the Coleto Creek drainage in northwest Victoria County.

We assume that the Clovis points represent the hunting of mammoth and other megafauna typical of the Late Pleistocene, but we do not have the data to meaningfully discuss regional subsistence patterns, group size, or mobility. Do the Clovis materials in the region represent small groups of highly mobile hunters, as some have suggested? Perhaps, but recent data from the Gault site, less than 200 miles to the north of San Antonio, has demonstrated that we are dealing with a population and a lifestyle that was considerably more complex than once thought.

Folsom points are more common than Clovis across the South Texas Plains, although they share a similar distribution across the landscape. Occasionally, a surface site will yield several Folsom points, such as site 41DM3 in Dimmit County. And like Clovis, some Folsom points have been documented in Tamaulipas along the lower Rio Grande. It is significant to note that no conclusive examples of this type have been found in central or southern Mexico. It appears that the Folsom points of the lower Rio Grande represent the southernmost extension of this type. In other words, the South Texas Plains may well have been the southern limit of Folsom culture.

As with Clovis, we are left to speculation about Folsom lifeways in southern Texas. So many of the known specimens have been found by artifact collectors at surface sites, and it is unclear whether any associated tool forms (such as the distinctive Folsom end scrapers) might have also been present, but not collected. On the Killam Ranch in Webb County, an unfinished Folsom point was found that is made of local Uvalde gravels. A number of the Folsom basal fragments seen in regional collections appear to be manufacturing breaks. Whether the presence of Folsom points in the South Texas Plains equates to specialized bison-hunting, as has been argued elsewhere, has yet to be established.

At the Wilson-Leonard site near Austin, Michael Collins and his associates recognized and defined the Wilson type, a stemmed Paleoindian dart point style first documented at the Devil’s Mouth site in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. These points are dated at 10,000-9500 years ago. In South Texas, Wilson points have been documented from the middle Rio Grande area and other parts of the region. For instance, numerous examples are known from the Mangold site, 41ME132, in Medina County.

By 10,500 years ago, the South Texas Plains region is thought to have been part of the widespread Plainview pattern, the definition of which has long been based on a kill site of Ice Age bison in the Panhandle. In the past, Texas archeologists used the Plainview label for just about any similarly shaped early point in the State, many of which did not look all that much like the specimens from the type site. It is still assumed the Plainview tradition is a real one, and that there are points in South Texas that may well be included into the type.

When the St. Mary’s Hall site (41BX229) in San Antonio was dug in the 1970s, a discrete Paleoindian occupation was found, with lanceolate point preforms, a bifacial Clear Fork tool, heavy end scrapers, and the bases of several points that were initially called “Plainview.” Fortunately, when the Wilson-Leonard site was dug a number of years later, some identical points were found and could be linked to radiocarbon dates suggesting that they dated between 9900-8700 radiocarbon years before present, definitely younger than Plainview. Recognizing the typological affinity with 41BX229, analysts named these points “St. Mary’s Hall.”

As parallel-sided “Plainview” points have been reexamined in South Texas assemblages, it is obvious that most of them fall within this new type. A locality on Cibolo Creek known as the Wilson County Sand Pit has yielded dozens, if not hundreds of these points (as well as other Paleoindian types), whose study has further defined the attributes of St. Mary’s Hall points, as found at the type site, Wilson-Leonard, and elsewhere. The points were found by sand-quarry workers during sorting and sieving operations and then sold to numerous artifact collectors. Many of these collections remain intact and need to be fully documented by professional and avocational archeologists. This locality may well have been a highly favorable occupation area comparable to the Gault site.

By far the best known Paleoindian cultural pattern in the South Texas Plains is the Golondrina Complex of about 10,000 years ago (8,000 B.C.), See Golondrina Complex.

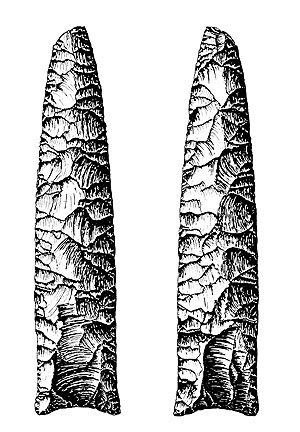

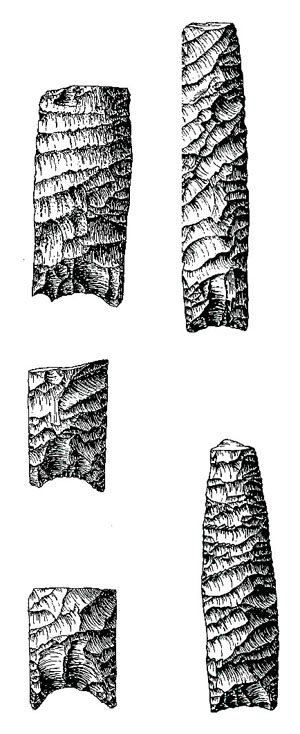

The end of the Paleoindian period is represented by Angostura and Scottsbluff points in South Texas. Angostura is even more common than Golondrina, and radiocarbon dates from the Richard Beene site in the South Texas Plains have securely dated the Angostura style to about 8800 years ago (6,800 B.C.). These points were extensively reworked during their use life, and specimens range from occasional large, well flaked examples to stubby reworked artifacts retaining only a vestige of the Angostura form. While the Angostura style is clearly a continuation of the Paleoindian lanceolate point tradition, many archeologists today consider this style represent the onset of the Early Archaic period.

Scottsbluff, a type normally thought to be most common in the Southern Plains, as well as in East Texas, is found at many sites in the South Texas Plains. Examples are reported from most counties in South Texas, and seem especially numerous in Victoria County (for example, at J-2 Ranch). Specialized Late Paleoindian “knife” forms, often reworked Scottsbluff points, known as “Red River” or very thin examples known as “Cody,” are found in East Texas and the Southern Plains, but not in southern Texas.

It is hoped that continued research will lead to the discovery of intact Paleoindian deposits in the region, of the sort already recognized in Victoria County. A better understanding of geomorphological contexts will doubtless guide researchers to preserved Paleoindian deposits. It was once hoped that excavations deep in the sediments of the Frio River drainage, such as those carried out before the Choke Canyon Reservoir filled, might expose Paleoindian components, but these deposits apparently do not date earlier than about 5,000 years ago. Similar situations probably exist along the Nueces. It may be that channel-cutting and scouring of the valleys of the Nueces and Frio by floods in ancient times may have removed most of the sediments of Paleoindian age, and the archeological evidence as well.

Along the Rio Grande, there are many deep terraces in which early occupations might be found. In the work at Falcon Reservoir in the early 1950s, one of the archeologists believed he had found stone flakes in direct association with mammoth remains, but this possibility was never substantiated. Many of the deep deposits are at the confluence of major creeks, coming in from the Texas side, with the Rio Grande. And many of these areas are on large ranches, within which major excavations are not encouraged.

Some of the buried paleochannels of extinct rivers, such as Palo Blanco in Kenedy County, hold a lot of promise. Excavations of Late Pleistocene mastodon, mammoth (one of which was partially articulated), horse, bison, glyptodont and deer remains at the La Paloma site did not provide definite associations of fauna and artifacts. The “age,” however, of the fauna seems right and the discovery of kill and butchering areas in that channel are only a matter of time and opportunity. Indeed, Sellards and Evans demonstrated, nearly 70 years ago, that the association of fauna and artifacts (of recognizable Paleoindian form) may well be found in the Berclair Terrace of the Mission River system in Goliad County.

Finally, research into Paleoindian archeology in the South Texas Plains should not be guided wholly by recognizable fluted points and lanceolate points typical of North America. There has long been a debate as to whether the bi-pointed Lerma point style dates to Paleoindian times, and there are hints that similar specimens may be very early. Most telling are the excavations done at La Calsada Rockshelter in Nuevo Leon, Mexico about 125 miles south of the lower Rio Grande. The earliest deposits at that site, radiocarbon-dated at 9,000-10,500 B.C., contained small bipointed, contracting-stem projectile points, not very carefully made, and which would not be recognized as to their antiquity if found on south Texas sites.

Contributed by Dr. Thomas R. Hester, professor emeritus, University of Texas at Austin, and former director of both the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory and the Center for Archaeological Research (UTSA).

Sources

NOTE: Any study of Paleoindian points on the South Texas Plains requires the researcher to review La Tierra, the journal of the Southern Texas Archaeological Association (headquartered in San Antonio), published since 1974. The STAA website, has an index that serves as a useful guide to a very large of number of papers related to the Earliest Peoples of the region. In fact, many of the drawings in this exhibit originally appeared in La Tierra and are shown here by permission of the STAA, a TBH partner organization, and illustrator Richard McReynolds.

Bettis, Allen C., Jr.

1997 Chipped Stone Artifacts from the Killam Ranch, Webb County, Texas.

TARL Research Notes 5(2):3-23.

Birmingham, William W. and James E. Bluhm

2003 A Clovis Polyhedral Blade Core from Northwest Victoria County,

Texas. La Tierra 30(3&4):55-58.

Brown, Kenneth M.

2006 The Bench Deposits at Berger Bluff: Early Holocene-Late Pleistocene Depositional and Climatic

History. Unpublished PhD dissertation (Anthropology), University of Texas at Austin.

Chandler, C. K.

1997 Complete Clovis Point from Wilson County, South Texas. La Tierra 24(1): 45-46.

Chandler, C. K. and Don Kumpe

1997 Early Paleo Points from the Falcon Lake Area of Tamaulipas, Mexico and South Texas. La Tierra24(1): 51-54.

Flaigg, Norman G.

1995 A Study of Some Early Projectile Points from the J-2 Ranch

Site (41VT6), Victoria County, Texas: The Schmiedlin-Studer

Collection. La Tierra 22(4):16-55.

Hester, Thomas R.

1968 Paleo-Indian Artifacts Along San Miguel Creek: Frio, Atascosa,

And McMullen Counties, Texas. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological

Society 39:147-162.

1971 An “Eolith” from Lower Pleistocene Deposits of Southern Texas. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 42:367-341.

1977 The Current Status of Paleoindian Studies in Southern Texas and Northeastern Mexico. In Paleoindian Lifeways, ed. By E. Johnson. The Museum Journal XVII:170-185. 170-185.

1988 Studies of an Obsidian Clovis Point from the Central Texas Coast and Other Paleo-Indian Obsidian Artifacts from Texas. La Tierra15(2):2-4.

Kelly, Thomas C.

1982 Criteria for Classification of Plainview and Golondrina Projectile

Points. La Tierra 9(3):2-25.

1988 The Nockenut Clovis Point. La Tierra 15(4):7-18/

Nance, C. Roger

1992 The Archaeology of La Calsada, A Rockshelter in the Sierra Madre

Oriental, Mexico. The University of Texas Press, Austin.

Sellards, E. H.

1940 Pleistocene Artifacts and Associated Fossils from Bee County,

Texas. With notes on artifacts by T. N. Campbell and Notes

on Terrace Deposits by Glen L. Evans). Bulletin of the

Geological Society of America 51:1627-1658.

Suhm, R. W.

1980 The La Paloma Mammoth Site, Kenedy County, Texas (with

notes on the archaeology by T. R. Hester). In Papers on the

Archaeology of the Texas Coast, edited by L. Highley and T. R.

Hester, pp.79-104. Special Report 11. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San

Antonio.