As shown in this map of Texas' natural

regions, Kincaid Shelter is located on the southern

edge of the Edwards Plateau in the scenic Texas Hill

Country. Map adapted from Texas Natural Regions map,

Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs.

Click images to enlarge

|

Although not present today, alligators

frequented the riverbanks during the era of Clovis people

in the Texas Hill Country. It was a time when the climate

was cooler and rains fell more frequently than today,

when the Sabinal River flowed year-round, and massive

Pleistocene animals roamed the craggy bluffs and canyons

of the plateau. Photo courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency.

|

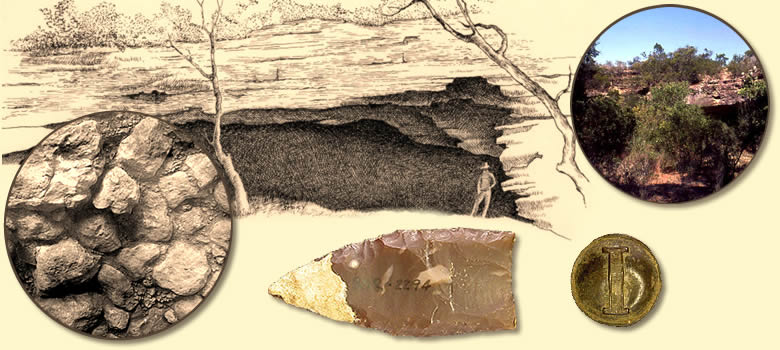

More than 13,000 years of culture

history is represented in these objects from Kincaid

Shelter. The small chert blade core at bottom left was

recognized by archeologist Mike Collins as evidence

that Clovis peoples lived at Kincaid long before Folsom

hunters came on the scene—and that they were almost

certainly the builders of the stone pavement. TARL Collections.

Photo by Aaron Norment.

|

Geologist Glen Evans, shown in one

of the long trenches his crews dug to expose the site's

stratigraphy, or layering. This prudent strategy provided

a "window" to the complex shelter deposits and guided

further excavations. TARL archives. Click to see full

image.

|

|

Kincaid takes our knowledge of Clovis beyond the

oft-repeated myth of nomadic "big-game hunters

following the herds" to a picture of ancient peoples

who selected a place to stay for an extended period,

improved their accommodations, and explored the full

bounty of the area's resources.

|

Archeologists and local people alike

had a keen interest in what was being uncovered at the

Kincaid Site. Here, U.T. anthropology professor T. N.

Campbell (center, front) and TMM director E. H. Sellards

(right ) give visitors a tour of the shelter in December,

1948, near the close of the first phase of excavations.

Photo by F. M. Bullard, TARL archives.

|

|

Although we will never know the full details

of its construction, the stone pavement at Kincaid Rockshelter

provides a rare glimpse into the mindset and way of life of

some of North America's earliest peoples. There is no doubt

that improving the shelter required considerable effort and

signified that the people who built it intended to stay for

a while, re-tooling their weapons and staging hunts and other

expeditions from that locale. But who were the builders, and

what was their life like, there on the banks of the Sabinal?

Based on a small array of distinctive tools

and the bones of now-extinct animals deeply buried in the

shelter's deposits, University of Texas archeologist Michael B. Collins believes

these early Hill Country stone masons were Clovis peoples.

If he is correct—and all evidence appears to support

this—the Kincaid stone pavement is the oldest known

structural feature in North America.

Located some 60 miles west of San Antonio, Texas,

Kincaid Shelter is significant as one of a mere handful of

Clovis-period occupation sites—a place where people

lived and invested their labor, unlike more-temporary open

camp sites and animal "kill" sites. As such, Kincaid

helps take our knowledge of Clovis beyond the oft-repeated

stereotype of "nomadic big-game hunters following the

herds" to a picture of ancient peoples who selected a

place to stay for an extended period, improved their accommodations,

and explored the full bounty of the area's resources.

Beyond Clovis, Kincaid Shelter also holds a

long record of later prehistoric peoples. Countless generations

of travelers and campers left behind tantalizing reminders

of their stay along the Sabinal River—Folsom hunters

on the trail of a wounded bison, a succession of Archaic period

peoples, and Late Prehistoric pottery makers and hunters wielding

bows and arrows. In more recent times, a traveler wearing

a Confederate uniform jacket lost a button in front of the

shelter, perhaps en route to battle in New Mexico. Over the

millennia, deep layers of sediment and human debris filled

the shelter and formed a thick terrace deposit outside.

Twentieth-century visitors, however, left a

very different imprint in Kincaid shelter—gaping holes

and mounds of shoveled-out backdirt. Searching for legendary

riches made famous by Texas writers such as J. Frank Dobie,

treasure hunters mined the deeply layered deposits of Kincaid

Shelter and, in the process, nearly destroyed its rich archeological

potential. When a young college student brought the site to

the attention of researchers, the fate of Kincaid Shelter

was changed, however, and its systematic exploration was begun.

Archeological investigations at Kincaid Shelter

were conducted in late 1948 under the direction of Elias H.

Sellards and Glen Evans from the Texas Memorial Museum in

Austin. One of the missions of the Austin museum, like others

across the country at the time, was to find and collect artifacts

of "early man" to fill displays and exhibits. Many

such collecting operations were done haphazardly, with an

eye more for the objects themselves than for understanding

their context.

Fortunately, Evans and Sellards took a more

scientific approach that was to be particularly critical in

verifying the age of the deepest cultural layers. As geologists,

Evans and Sellards were keenly aware of the importance of

depositional processes and stratigraphy. After clearing and

sifting the backdirt, they excavated a deep trench from the

front to the back of the shelter in order to gauge the depth

and character of the shelter fill. This critical process,

unusual by archeological standards of the time, provided a

vertical "window" to view the complex layers of

shelter deposits and guided further excavations.

Five years later, University of Texas anthropology

professor Thomas Nolan Campbell led a field school to investigate

the deep terrace deposits directly in front of the shelter.

Although it later became evident that the deepest layers of

the terrace formed after the critical Late Pleistocene "early

man" levels inside the shelter, the terrace investigation

provided additional information on the Archaic and more-recent

cultures.

In the following sections, readers can learn

more about Kincaid Shelter, from its serendipitous "discovery,"

to systematic excavations by geologists and archeologists,

to trials and errors with trailblazing scientific techniques,

and finally, to the re-analysis of a few stone tools that

solved a decades-long mystery. In the process, readers will

see glimpses of the ancient—and more recent—peoples

who visited and investigated the shelter along the Sabinal.

In the first section, we explore the site in

its Natural Setting in

the scenic Sabinal River valley. In Discovery

and Investigations, we learn of the events that led to

the site's discovery by Charles E. (Gene) Mear, whose career

path in geology was charted at Kincaid, and track the investigations

at the site by the TMM and UT-Austin.

Reading the Layers

interprets the shelter's complex natural stratigraphy, discusses

how the deposits accumulated, and looks at the cultural materials

discovered in the various zones. Examples of the hundreds

of artifacts recovered at Kincaid are presented in Fragments

of the Past. A special gallery, Mysterious

Stones, highlights prehistoric artistry at Kincaid: an

array of pebbles, some engraved with a variety of enigmatic

patterns, others used to make red pigment. All artifacts shown

in the exhibits are curated at the Texas Archeological Research

Laboratory at UT-Austin.

In Kincaid

Revisited: Clovis and Beyond, the story of archeologist

Michael B. Collin's serendipitous involvement with the site

unfolds, and the Paleoindian evidence is examined further.

We also look at Kincaid's significance within the North American

archeological framework.

Learning about Kincaid is a special section

now under development for teachers and students. The first

activity, Kincaid Creatures, challenges students

to identify the various animals—both extinct and modern—

represented at the site and to understand the concept of stratigraphy.

Watch for more activities and lessons to be added.

The Credits

& Sources section provides brief biographical sketches

of the Kincaid researchers and references and links for learning

more about various topics in the Kincaid exhibits.

|

Rolling, tree-covered hills and narrow

valleys cut by crystalline streams are hallmarks of

the Texas Hill Country. Prehistoric hunters and gatherers

were attracted to the rich resources—water, game,

and fuel, just as travelers are today. Photo courtesy

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

|

Like postcards from the past, the

fragments of ancient tools, weapons,

bones, and stones have a story to tell.

But, deplorably, the rich archeological

potential of Kincaid Shelter was plundered,

its deep layers of evidence nearly destroyed

by treasure hunters who left gaping

pits and piles of backdirt in their

wake.

|

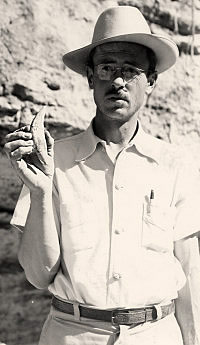

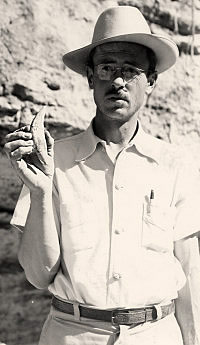

Paleontologist Grayson Meade holds

the massive canine of a cave lion, one of many now-extinct

species that prowled the Edwards Plateau during the

Late Pleistocene. The tooth and a variety of other fossil

bones were recovered in the deeper layers of the shelter

that pre-date human use. TARL archives.

|

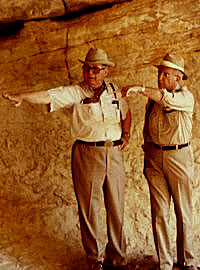

Posed in a trench below the early

rock pavement, Texas Memorial Museum Director E. H.

Sellards, a geologist and paleontologist by training,

examines the deposits under the feature. TARL archives.

|

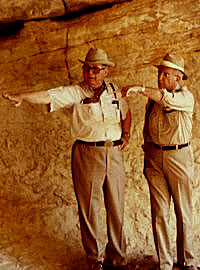

Returning to Kincaid after more than

40 years, geologists Glen Evans and Gene Mear recall

details of excavations at the site. It was Mear who

brought the site to the attention of researchers at

the Texas Memorial Museum in 1948, after finding several

rare Folsom points. Photo by Tom Hester, TARL archives.

|

|