Indian Intruders From the North

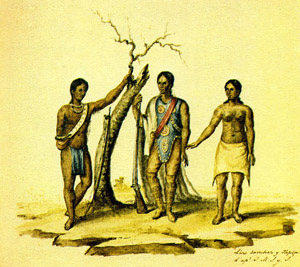

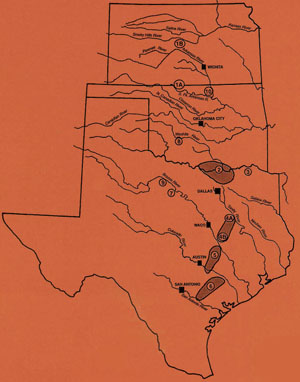

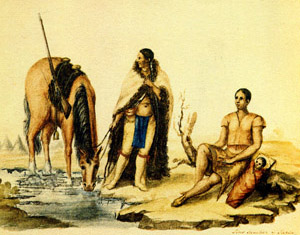

Plains Indian warrior, inset from painting, “Comanches on the Trail,” by Theodore Gentilz, ca. 1840s. Original painting in Witte Museum. Historic Indian tribe locations map, ca. 1832, adapted from Hester 1989, Fig. 31. |

Indian Intruders: Comanche, Tonkawa, and Other TribesBy as early as the late 1600s, outside Indian groups had begun moving onto the South Texas Plains, accelerating the demise of the region's vulnerable indigenous peoples. Among the new intruders were the Tonkawa, the Lipan and Mescalero Apache—groups which themselves had been displaced from their home territories far to the north and northwest. The availability of a new transportation system, horses, transformed many Plains Indian groups into societies that are sometimes characterized as "horse nomads." First and foremost, were the Comanche, who with the Kiowa, raided through south Texas and across the Rio Grande into northern Mexico. They were formidable foes to other native peoples as well as Anglo settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Facing increased hostilities, more competition for resources, and ravaged by Old World disease, local native groups were either pushed south into Mexico or assimilated into the new, more dominant tribes. In late prehistoric times, the Lipan and Mescalero Apache lived in the Southern Plains of the United States. By the late 1600s, they found their homelands threatened by the Comanches and by Spanish raids seeking slaves for the silver mines around Parral and Chihuahua City or for the large ranches of what is today northern Mexico. To avoid those fates, they moved south and east, eventually reaching south-central Texas. As the tumultuous times unfolded, some Apache attempted alliances with other native peoples, including the Jumano and Tonkawa, groups with whom they had had hostile relationships in the past. By the late 18th century, the Apache were pressing south across the Rio Grande and east into the South Texas Plains and brush country, where they began to align themselves with other native peoples. They chose this region, in part, because it had not been heavily settled by the Spanish, with the exception of the ranchos along the Rio Grande in the colony known as Nuevo Santander and the mission settlements there and in San Antonio de Bexar. Although they lived a hunting and gathering lifestyle, the Lipan Apaches were mounted warriors who also raided homes and ranches for cattle and sheep. But as threats from Comanche and other groups intensified, the Lipan sought refuge in Spanish missions, including Santa Cruz de San Sabá (on the Edwards Plateau). In the second half of the eighteenth century and, after the mission on the San Saba River was destroyed by an allied force of their enemies, the Apache moved farther south, extending their range from the Bolson de Mapimi desert in north-central Mexico to the Rio Grande to the Nueces. In 1772, 300 Lipan Apache attacked haciendas and pueblos in Coahuila. In the ensuing century, few Europeans settled in the region, and those that did, such as Richard King

(founder of the fabled King Ranch), found that the key to success was the acquisition of vast lands for

ranches. Thus, although the region was distant from their Southern Plains homeland, Lipan and Mescaleros

found a refuge here until the early 1900s when they were forcibly moved onto a reservation in southern New

Mexico where they reside today. TonkawaAlthough chiefly operating on the northeastern fringe of the area, the Tonkawa also played a role in the region’s history. Much has been made about whether the Tonkawa were an actual tribe or, rather, an amalgam of other groups and splinter tribes, some of which were from south Texas. Most likely, they were a bit of both and absorbed different peoples in later historic times. The Tonkawa were first documented in 1601 in an area north of Texas on the Arkansas River, where the Wichita-speakers called them the Tancoa, a word meaning “they all stay together.” In their own language, the Tonkawa called themselves Titskanwatits, meaning “people of the country” or “Indian people here.” At that time, these hunting and gathering peoples lived in a number of large villages, but they faced increased conflicts with other native peoples. By the late seventeenth century, they were residing in Texas and were called the Tanquaay. During the late eighteenth century, they lived with various groups over a wide geographic area, ranging from the Red River to the area of present Waco, and, at times, even further south into the South Texas Plains. Much of what we know of the Tonkawa during this period comes from documents written by a Frenchman named De Mezieres who visited them on several occasions in the 1770s, often in their camps close to the Red River. He estimated their population at about 500 and described them as hunters and gatherers living in tents and hunting buffalo and deer—both to eat and to obtain the animal skins that they traded. By the late eighteenth century, the Tonkawa had absorbed several other Native American groups who sought protection within the larger Tonkawa nation. Some—such as the Sana and Yorica—were originally from the South Texas Plains and northern Mexico. These added numbers strengthened the increasingly threatened Tonkawas and helped them survive attacks by Apaches and others. Later, the Tonkawa served as scouts for the U.S. Army in west Texas during the Indian wars. In spite of their valued service, however, they were removed to a reservation in Oklahoma in the late 1880s. (See Tonkawa Tribe website.) Comanche and Other GroupsThe Comanche, latecomers to the South Texas Plains, were among the most feared. Indeed, the name, Comanche, is believed to be a Spanish version of a Ute word meaning “someone who wants to fight all the time.” By the early 18th century the Comanches had moved from Colorado into New Mexico, where they alternately raided and traded with Spanish settlements. Their attacks upon pueblo Indians and the Apache were nearly constant. Throughout the 1700s, the Comanche continued to move to the southeast, driving deeper into Texas and pushing the Lipan in their wake. Having established control of the Southern Plains, the Comanche moved onto the Edwards Plateau and beyond, where they secured their dominance by entering into a truce with the Spanish in New Mexico and forming an alliance with the Kiowa. (See Comanche Nation website.) Other tribes who are known to have had a brief presence in the South Texas Plains were the, Shawnee, Caddo, Kiowa, Kickapoo, and Seminole. While not all were hunters and gatherers, their activities in this sometimes harsh region generally mimicked those of the hunters and gatherers whom Cabeza de Vaca and his companions had met and lived among some 300 years earlier. To learn more about Indian groups in Texas during the Historic Period, see the following exhibit sections on this website: |

|