Who Were the "Coahuiltecans"?

|

|

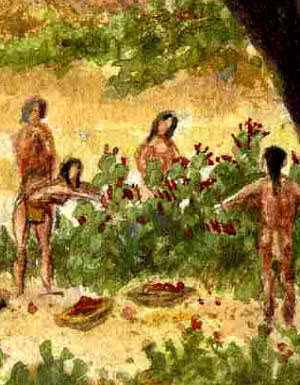

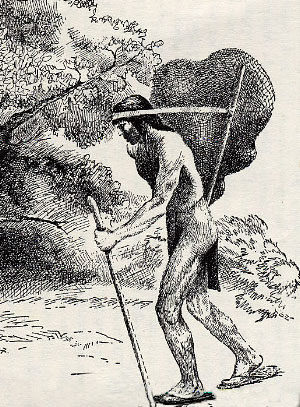

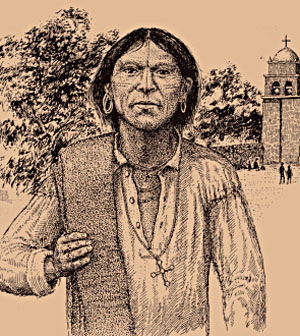

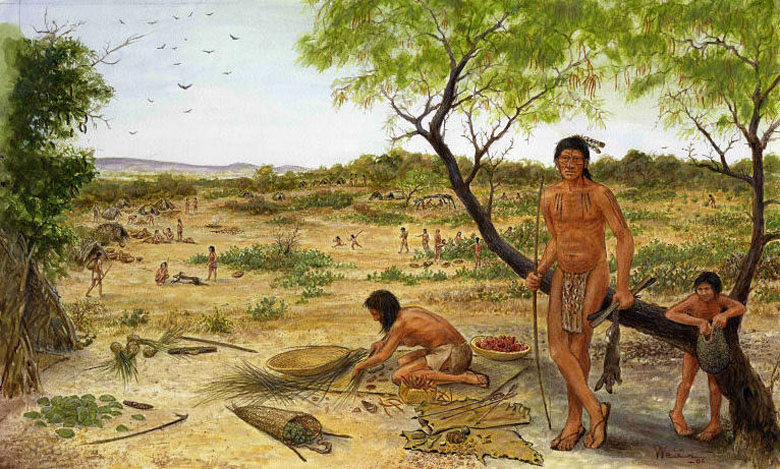

When the South Texas Plains first entered into written history in the 16th century, hundreds of small, highly mobile groups of hunting and gathering peoples ranged across southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. The seasonal rounds of some extended to the margins of the Gulf Coast; others periodically probed the higher country on the southern part of the Edwards Plateau. Many spent their summers among the enormous fields of prickly pear cactus on the South Texas Plains, harvesting the ripe fruits and joining with others in work, trade, and celebration. These groups varied in size, often seasonally, as small family bands of a few dozen people came together with other bands who all spoke the same dialect and, collectively saw themselves as one people, or what the Spanish often called naciones, and we might call tribes. Examples of relatively large named groups that we know the most about are the Payaya of the Medina River valley, the Pacuache along the Nueces River, and the Mariames along the lower Guadalupe River and farther inland to the west. There were dozens and dozens of others, most of which we know almost nothing about except maybe a name. Collectively, all these groups have come to be known as Coahuiltecans, but they spoke diverse dialects and languages, some of which were distantly related to one another at best. Some of the major languages were Comecrudo, Cotoname, Aranama, Solano, Sanan, as well as Coahuilteco. Some groups got along with one another and shared partially overlapping territories, particularly in the prickly pear season. Other groups were sworn enemies of one another or simply had such widely separated territories and language differences that they rarely came in contact. Although all were hunters and gatherers, some derived their main livelihood from quite different resource bases at various times of the year. In other words, the term Coahuiltecan masks considerable ethnic and behavioral diversity. In this exhibit set we use the term Coahuiltecan in its proper sense, a geographic catch-all that could also be described as "the native peoples of south Texas and northeastern Mexico." As explained in the Native Peoples Main section, the term is greatly misused and misunderstood. For better or worse, Coahuiltecan is ingrained in both scholarly and popular literature and all we can do is try to explain what it means and use it correctly. It is simply a geographic term that encompasses virtually all of the diverse human groups who called the South Texas Plains, including its western segment in adjacent northeastern Mexico east of the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range. Like the colorful and distinct patchwork pieces of a quilt, many of the diverse "Coahuiltecan" groups derived from different sources but all were tied to a common backing—the land and its resources. The stories of the native peoples are all the more remarkable when we consider that many of the native peoples of the South Texas Plains may well have been direct linear descendants of the Paleoindian peoples who came to the region more than 13,000 years before, and whose descendants stayed on. That fascinating inference is based on the linquistic diversity of the Coahuiltecan groups, and the fact that several of the region's languages are unique and not closely related to any languages elsewhere in the world. Said otherwise, places where language "isolates" are spoken are likely places where people lived continuously for thousands of years. A better known example of this phenomenon is Basque, a language isolate spoken in the Pyrenees in north-central Spain. Hunting and Gathering on the South Texas Plains Food resources in the grassy plains and brushlands of South Texas were richly varied, and these helped to define the subsistence strategies of the various Coahuiltecan groups. One of the most important staples for the native peoples of the region was the nopal, or prickly pear cactus. Vast concentrations of prickly pear were noted in the historical record in several areas of the South Texas Plains. In the 19th century one traveler described a concentration along the Nueces River as “immensely large and branching through which nothing can pass…no man, nor beast will attempt to penetrate them.” Other concentrations were seen in modern Live Oak, Duval, Jim Wells, Nueces and Kleburg counties. Cabeza de Vaca and his companions, who lived several years with native groups along the Texas Gulf Coast, described traveling inland in late spring and early summer each year to gather and eat the tunas as well as their pads. In his Relacion de los Naufragios [Account of the Shipwreck] published by the Spanish court in 1555 and republished in 1906, Cabeza de Vaca described the harvesting of these odd fruits, noting that such seasonal occasions were also an important time for social interactions and trading with other native groups: This is a fruit that is of the size of an egg, and they are red and black and of very good flavor. They eat them three months of the year, in which they eat nothing else, because at the time they gathered them there came to them other Indians from farther on who brought bows, to trade and barter with them. When Cabeza de Vaca and his companions stayed with the Arbadaos and the Cuchendados, it was the beginning of the tuna season and many were ill with hunger and anxiously awaiting the ripening of the tunas. Nonetheless, despite their scarce food resources, the Arbadaos took the Spaniards by the hand into their dwellings and fed them, a kindness that would be welcomed today. The food they fed them were unripened tunas, which were bitter and hard to digest, and roasted pads of the prickly pear. They also gave the men two dogs in exchange for nets and other items such as the skin Cabeza de Vaca had used as a blanket at night. Another food resource mentioned when the travelers were in the settlement of the Cuchendados was the mesquite bean, which was processed to provide a type of flour that could be mixed with other foods. The bean was also used in a ceremony that is described by Cabeza de Vaca. Adult males pounded the seed pods in a pit in the earth, mashing them until they were very fine. The finely ground seeds were then mixed with earth in a basket, and water was added. All members, including the Spaniards, then ate the gruel which, although sweet, greatly distended their stomachs. The Spanish explorer provided a few other rich details about the two groups. As noted above, the Arabadaos extended their hands in friendship to the strangers even though they were in a season of scarce food resources. The Cuchendados also treated the men with care, providing food for them, and also hosting a ceremony for them. Cabeza de Vaca tells us: The Indians [Cuchendados] made great celebration for us and among themselves very great dances and songs as long as we were there. And at night when we would be sleeping at the entrance to the camp where we were…six men would keep watch over each one of us with great care. The reasons why the Cuchendados took such care with the four Spanish is never made clear and we wish more details had been given. Perhaps the Cuchendados knew enemies were nearby and they were protecting both the Spanish as well as their own people. Perhaps the presence of the four was a novelty that gave the Cuchendados greater esteem. Or, less kindly, perhaps they thought to keep the four with them indefinitely. When the Spaniards left the Arbadaos and the Cuchendados, Cabeza de Vaca recalled, both groups wept. While such weeping might be expected if family members were leaving on a long journey, it seems to be an unusual occurrence when you have only known the travelers for a short time. And, it was sufficiently unusual that the Spaniards remembered this detail several years later after they had survived an incredibly difficult journey. Other personal glimpses are provided in the Spaniard’s account, significant because they clarify the roles and abilities of women in one group. He reports that women from another nacion south of the Rio Grande were in the Cuchendado settlement at the same time as the Spaniards. In fact, these women guided the Spaniards to their settlements south of the river. Since neither the Spaniards nor the Cuchendados thought this odd, apparently women traveled on their own with some frequency. Moreover, the Cuchendados told the Spaniards that there was “no trail” to the women’s settlement. In other words, the women must have navigated across the region from one settlement to another by following the terrain and natural landmarks. That was simply their way of life, but when we think of traveling on foot, without the modern conveniences of hotels, cars, GPS units, and highways, it gives us pause—the lives of these ancient men and women was a lot more challenging than "hunting and gathering" implies. The Mariames: Hunter-Gatherers over Diverse Terrains Cabeza de Vaca lived among another group, the Mariames, for some 18 months (although not by choice). The Mariames followed a hunting and gathering strategy based on the exploitation of contrasting sets of resources found in two geographically separated terrains. For the greater part of the year, they lived in the lower Guadalupe River valley, hunting along the coastal plain, gathering pecans along the river, and other resources. Both deer and bison were among their prey, according to the Spaniard's account. One "hunting" method he witnessed involved setting fire to the prairie grasslands and chasing fleeing deer into the bays and forcing them to swim until they became exhausted and drowned. Not very "sporting" as we would see it, but hunting wasn't a sport, it was life or death. In the summer, the Mariames moved dozens of miles inland to the west to the prickly pear fields, where they stayed for months to harvest ripe tunas. While there they gathered land snails to supplement their diet, a meager caloric addition at best. But rats, rabbits, and snakes would have been on the menu as well. In the hot, dry summer months, they squeezed tuna juice into holes in the ground and used it as an earth-flavored beverage. During their summer time at the tuna fields, the Mariames met with other groups, such as the Avavares, with whom they traded for items such as wooden bows for hunting. Mariame encampments—rancherias—were described as a succession of small circular huts made of four bent poles covered with woven mats made of plant fiber. After the land's resources had been exhausted in one spot, these simple structures could be easily disassembled. The parts that were difficult to make (eg., the mats) were packed up and moved to the next camp. Cooking was done in small pits or on open hearths, but many foods were eaten raw, all organic, all natural. The Payaya Most of what is known about one of the Coahuiltecan groups that resided on the upper South Texas Plains, the Payaya, comes from an extensive study by ethnohistorian and anthropologist T. N. Campbell. Mentioned in many 17th and 18th century documents, the Payaya were associated with a broad area that included San Antonio and probably the southern edge of the Edwards Plateau. Like the other naciones with whom they shared a language, they were mobile hunters and gatherers, but while they shared cultural traits with other Coahuiltecan speakers, they also likely had their own unique habits that made them the "Payaya” and not “Pachuache” or “ Sana.” As Campbell emphasized, the known traits and traditions may not be characteristic of other groups in the region at the time of European contact. Between the years 1688 and 1717, various Spanish expeditions found the Payaya in camps along the western and northern margins of the South Texas Plains. Given the fact that several times the Payaya were found camped in modern Bexar and Medina counties, it is likely that this was a core part of their homeland. Keep in mind that the Spanish view of the native world was rather narrow: Spanish expeditions tended to follow the same northeast/southeast line of travel from the Rio Grande to San Antonio and then on to east Texas that was first taken in 1690. Thus, their documentation of the overall Payaya territory was incomplete. The natives' actual range may have been much broader than we know. Spanish accounts make it clear that pecans were an important food source. The Spanish found the Payaya at locales where they were gathering pecans, sometimes in “great quantities.” While the type of nuts being gathered in great quantity were not specified, the presence of the Payaya in Bexar and Medina counties makes this clear. Even today pecan groves continue to be prominent along the Medina River. Fray Espinosa describes pecans in detail in his encounters with the Payaya in the region in 1709. Given that pecan trees in each area tend to produce crops only every second or third year, the Payaya could not have counted on abundant harvests each year. One way they stored excess pecans for later use was by placing shelled pecans in small skin bags or threading them on long strings. Both methods would allow for easy transport from one camp to another. The Payaya seem to have maintained close friendships or alliances with certain other naciones, including the Pampopa, Cauya, Semomam, Saracuam, Pulacuam, and Anxau. Although the Spanish documents never specifically state that Payaya were friends or allies of other groups, we can infer this based on the groups they were seen camping or traveling with. Thus, we know the Payaya—and other small groups of the South Texas Plains—through the shadowy and spotty view of Spanish documents. The known documents offer only a few details about their range and their hunting and gathering lifeways. Campbell believes that they resided, at least seasonally, in the San Antonio area. Although definite archeological evidence of the Payaya has been difficult to pin down, no evidence has been found that contradicts the notion that they consisted of small familial or multi-family bands that moved seasonally through the San Antonio and South Texas area. Absorption and Extinction By the early 1700s, the Spanish had begun establishing missions for the Indians of south Texas and northeastern Mexico. Although there are voluminous records of native families, their marriages, baptisms, and conversions, as well as journals of the priests describing the trials and triumphs of the various mission populations, there is not a great deal that can shed direct light on specific groups. For the most part, native groups that entered the missions were remnant groups whose societies had been ravaged by disease, reduced by warfare, and pushed in every direction from intruding peoples from the outside, European and Native American. Many survivors from disappearing groups joined with other groups, further diluting and distorting their cultural identities. Others intermarried with the Spanish, as anthropologist Mardith Schuetz has demonstrated. Some small native groups, such as the Cacaxtle, had turned to raiding Spanish settlements along the Rio Grande, emulating the larger and more formidable Plains groups. Drawing the attention of the Spanish military, the Cacaxtle were effectively annihilated in two battles. During the second, fought in 1665 in modern-day Kinney County, the natives fought from within a defensive fortification built of tree trunks, branches, and prickly pear plants. During the battle, a lone native woman reportedly played a flute, perhaps to buoy the spirits of the Cacaxtle warriors, but in effect, sounding the death knell of her people. Following Cabeza de Vaca’s journey in the early 1500s, only a few hundred years passed before the indigenous peoples of the South Texas Plains had lost almost all ethnic identity and were, effectively, culturally extinct. Although their languages were no longer spoken, those native peoples who survived the Mission era were absorbed within the Mexican communities that formed around the abandoned missions. Some of their genes and memories were passed on and today there are several "resurgent" groups who trace their heritage to the Coahuiltecans of yesteryear, including the "American Indians in Texas at Spanish Colonial Missions" and the "Tap-Pilam-Coahuiltecan Nations." Archeologist and anthropologist Alston Thoms suggests that the concept of "cultural extinction," as it applies to geographic Coahuiltecans, should be viewed in relative terms. He points out that elements of their lifeways survive to the present, including foodways (e.g., nopal and tuna), religion (Native American Church), and other behavior, and that some Coahuiltecan words are embedded in rural Spanish. In short, he argues that aspects of geographic Coahuiltecan culture survived long after their hunter-gatherer lifeways and languages ceased to exist and that such cultural survival is manifested by resurgent groups such as Tap Pilam. |

|