In spite of all of the activity around him, John, just six years old, is concentrating on the book in his lap. Ransom Williams was no doubt proud of the fact that his children could all read and write even though he and Sarah could not. Prior to the Civil War, it was illegal to teach enslaved African Americans to read and write in most Southern states.

The Williams children were most likely educated in the community schools, either in nearby Antioch or Manchaca. Education was valued highly by the African-American community who recognized that learning to read and write was an important part of being able to succeed economically and to participate fully in civic life. Although the county and state government were often unwilling to give much support to African-American schools, freedmen communities like Antioch found ways to build and fund educational opportunities for their children.

See what the archeologists found!

Some of the artifacts found at the farmstead are related to learning how to read and write. These items are evidence that the Williams children were receiving an education, perhaps by traveling to the school at nearby Manchaca or the Antioch colony.

Archeologists determined from looking at old records that Ransom and Sarah did not know how to read or write. However, they obviously valued the idea of education and did what they could to make sure their children were literate.

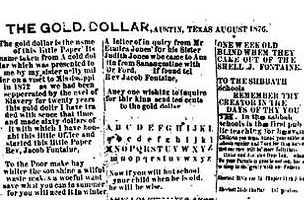

African-American newspapers in nearby Austin also stressed the importance of education, particularly for freedmen and their children. One newspaper editor even published the alphabet for children to use in their studies at home. Education was considered a key step on the road to freedom.

In the 1800s, many children learned to write using slates and slate pencils. Because paper and pencils were relatively expensive, students often did their daily classwork and practiced skills such as handwriting and math on a framed piece of black slate, known as a slate table. The teacher or an older child would check the work, then the student could erase the assignment and begin the next one.

Archeologist found two large pieces of broken writing slates. One of the slate fragments has some symbols on it that were engraved with a knife blade or other sharp-pointed object.

They also found several broken slate pencils at the farm. Slate pencils were made of a soft stone, like talc or soapstone, which could be erased.

Several pencil erasers and bits of graphite pencil leads from wooden pencils also were found at the farm site. These writing utensils are more familiar to modern school kids. One specimen has its original gum eraser and part of the wooden pencil still encased within the ferrule. Another type of writing tool found at the farm were carbon battery rods that had been sharpened on both ends. These may have worked just like pencils, leaving a heavy black mark on surfaces.

The Williams children may have done their studies in the evening on the porch, but in the winter they may have worked by lamplight inside the cabin. Archeologists found a variety of lamp parts at the farm site, including the burner mechanisms. These sections rested on top of the base that held the kerosene or other oil that was burned to make light. These pieces probably came from a lantern that once had a glass globe held in place by a metal frame. No rural homes in Texas had electricity until the 1930s or even later, so lanterns were the only source of light in the evening.