Investigations at the Old Socorro Mission

|

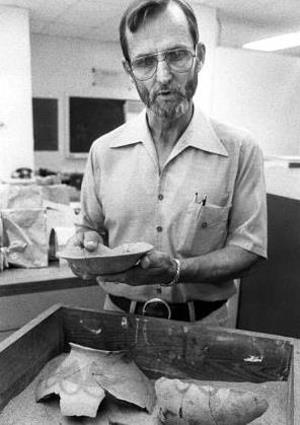

Excavations underway at 41EP1532, site of the Old Socorro mission. Surrounded by modern neighborhoods, the site lies on the north bank of the Rio Grande, south of El Paso. TARL Archives.

|

|

|

|

|

Pottery sherds were the most prevalent artifacts recovered from the Old Socorro Mission and the most useful for relative dating. Brownware sherds dominated and were found widely scattered over the surface and in many subsurface deposits. All are undecorated except for several that could be reconstructed into two vessels. The first is an incised vessel depicting a figure with a human face and the body of a toad. The second, found in Room 4, is a jar painted in red depicting a human head on the body of a lion next to a "sacred heart. " These motifs reflect a merging of native and European decorative traditions. Ceramic specialist David Hill has suggested the "grotesque" figure on the second vessel is a symbol of power in the Catholic faith, and the three triangles atop its head may be a crown or rays of the sun. He believes the vessel is unique in the El Paso area for the time and likely was an object made especially for use in the church, perhaps for special display. Other vessel forms that could be derived from the sherds include hemispherical bowls, soup plates, small jars, and candlesticks. These ceramics are similar in many respects to indigenous brownwares found throughout the American southwest and northern Mexico and were likely made by the Piro or mestizo inhabitants of the site. Two sherds of Tewa Polychrome, a late 17th-/early 18th-century type attributed to the Pueblo peoples of north central New Mexico, were also recovered. Several variants of Mexican-made tin-lead glazed earthenware (majolica) were identified at the site. Fourteen sherds of Puebla Polychrome, which dates to the 17th century, 1 sherd of Augustin Blue-on-white, which dates to the early 18th century, 17 sherds of Puebla Blue-on-white, which dates to the 18th century, and 1 sherd of Heujotzingo Blue-on-white, which dates from the late 17th century to the present, were recovered. Several unidentified sherds of a green-on-white or yellowish-on-white glazeware that likely dates to the 18th century were also found. Other types of artifacts recovered from Old Socorro Mission include metal, glass, and stone. A small copper candlestick was found that likely dates to the early 18th century. The other metal artifacts, which could not be dated, include a tack, the handle of a copper teaspoon, a crucifix from a burial context, a few small medals from a burial context, a heavy rectangular braid of copper wire that is presumed to be some kind of ornament, and a flat disk of thin silver sheet with a round hole in the center that is also presumed to be an ornament. The only glass artifacts recovered from the site were a single fragment of black glass and several beads. Most of the beads appear to have belonged to a single rosary. Some are tubular, translucent "ave" beads, two are octahedral, translucent specimens that resemble rosary beads manufactured in Italy during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and several were made of clay and green, platted thread. The rest of the beads were found in a burial context and appear to have been decorative. The only stone artifacts found at the site are a ground stone pestle and a gunflint made of a kind of chert that does not appear to be local to the southern Tularosa basin. Thirty-two burials and hundreds of disarticulated and fragmented bones were recovered from beneath the floor of the nave of the church, in line with the transept. Interment so close to the altar of the church strongly suggests that these were high-status individuals, likely Piro leaders, and their close kin. Though these burials are not representative of the general population of the Old Socorro Mission, they nonetheless reveal information about its people and how they lived. Only the intact burials were analyzed. They are fairly representative of all age groups, consisting of 2 fetuses, 10 infants and children under the age of 5, 2 children aged 9 and 11 years, and 18 adults. The burials of the infants and young children are roughly contemporaneous, suggesting an epidemic of a disease that young children are particularly susceptible to. All of the adults show Native American/mestizo morphological traits. They were in good health and did not suffer from malnutrition. They consist of thirteen males and only five females. Interestingly, females were younger than males. All of the females were under 50, as opposed to only 4 of the males. The good health and the disproportionate number of older males among the adult burials further suggests that these were Piro leaders who enjoyed high status in the community. Archeological indicators of diet from the Old Socorro Mission are rather meager. No plant remains were recovered and the only identifiable faunal remains were the core of a cow horn and fragments of turkey eggshell. It is unclear whether the turkey was wild or a domestic variety kept by the people of the mission. Dietary isotope analysis, a chemical study of small samples of bone, has helped us to understand what these individuals were eating. Since various categories of plants and animals have different levels of stable carbon (13C) and nitrogen (15N) isotopes they act like tracers that leave a record in an organism’s tissues as the carbon and nitrogen moves from the environment to plants and animals and their consumers including people. These tracers allowed us to identify some of the classes of food the people consumed. Based on these studies, wheat and barley made up a more significant portion of their diet than corn, and they appear to have eaten few if any beans. They received an adequate amount of animal protein in their diets that came largely from domesticated animals, such as sheep, goats, and cattle, and was supplemented by aquatic animals. Females appear to have consumed more or a greater variety of protein than males. These high-status inhabitants of the Old Socorro Mission appear to have subsisted largely on European domesticates, but native domesticates and wild resources may have held more importance in the diets of the lower status inhabitants of the mission. After the relocation of the El Paso missions in 1684, Socorro became the largest native community in the area. Despite this, the native people of Socorro were the first to lose their native identity by intermingling with each other and the Spanish. In 1760, the ratio of Spaniards and mestizos to Indians at Socorro was 2:1. This jumped to 10:1 in 1803. By this time, the Tano and Jemez had disappeared, leaving only the Piro. When Southwest historian and archeologist Adolph Bandelier visited Socorro in 1883, he found that the Piro language had been completely replaced by Spanish, and Socorro had become indistinguishable from small Mexican villages. When archeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes visited in the 1890s, he observed that ceramic manufacture had ceased. The reason for the rapid assimilation of Socorro is likely the fact that it was home to three different native groups. This heterogeneity would have encouraged the use of Spanish as the lingua franca and made the maintenance of tribal rituals, particularly secret rituals, difficult. The mission of Ysleta, in contrast, was home to only the Tigua, and is the only El Paso mission that has maintained its native identity. The archeological investigations at the Old Socorro Mission reveal the ways in which the native people of the mission combined their way of life with that of the Spanish. They maintained their ceramic brownware tradition, but also used imported Mexican ceramics. Their diet, or at least the diet of higher-status individuals, was largely based on European domesticates, but they continued to fish from the Rio Grande and grow corn. This blending of life ways created a unique culture at the Old Socorro Mission and the community surrounding it that lives on today in the modern town of Socorro.

|

|