Native Peoples of the Coastal Prairies and Marshlands

in Early Historic Times

The Texas coastal prairies and marshlands is a region abundant in diverse resources. Bordering the Gulf of Mexico, with its bays, estuaries, and barrier islands, and tracking inland into sandy dunes, brackish marshlands, floodplain forests, and prairie grasslands, the narrow region winds along the coast for more than 600 miles, from Port Arthur to Brownsville. For thousands of years, aboriginal peoples fished and collected marine resources along the sandy shores and trekked across the prairies and marshes in search of wild game and fruiting plants. In more recent times, remnant groups of these longstanding cultures—the Atakapa, Akokisa, Karankawa, Mariames, Comecrudos, and others unnamed—were encountered by European explorers, soldiers, and missionaries. Their prodigious journals and official reports provide first-hand glimpses of the region’s native groups engaged in traditional lifeways which, in many cases, had changed little over the centuries: fishing and collecting shellfish from the bays and lagoons, and hunting and gathering wild game and plants across the prairies and river valleys. Among the earliest accounts of native peoples are the 1537 journal of Cabeza de Vaca and the 1680s chronicle by the Frenchman Henri Joutel, one of La Salle’s colonists on the Texas coast. These accounts differ greatly in perspective: Cabeza de Vaca and his shipwrecked companions lived as captives among a succession of native groups in south Texas and along the coast. As a condition of his existence, he “became” a native, performing grueling labors alongside native women: grubbing for roots “from morning to night,” gathering plants and fruits, and scrounging for firewood. As such, his accounts are an insider’s view in the truest sense, providing unprecedented details about native lifeways (see the TBH exhibit Learning from Cabeza de Vaca for a detailed account of Cabeza de Vaca and his journeys). Joutel’s diary, written some 150 years later, is written from the perspective of a colonist—albeit a hapless and unintentional one—encountering native groups (chiefly Karankawa) who viewed La Salle and his colonists at Fort St. Louis as unwelcome intruders in their land. The Frenchman, intent on sustaining the meager colony in the wilderness while struggling with the erratic behavior of La Salle, made little mention of native ways, other than recording their periodic threats and attacks on the settlers. Spanish expeditions across the region during the 17th and 18th centuries produced numerous documents mentioning their encounters with native groups. All of these eyewitness accounts of native peoples practicing traditional ways help us bridge the gap between the distant prehistoric past—represented by mute artifacts and traces in the dirt—and the modern world. From these records we learn that, although the many native groups along the coast had their own distinctive traditions, languages, and names for themselves, they shared an intimate knowledge of the land and resources of their area. Many practiced similar subsistence strategies, involving seasonal migrations from the coastal shores to the inland prairies to harvest resources as they became available. But the coming of the Europeans—as well as intruding native raiders, such as the Comanche, Tonkawa, and Apache—triggered devastating cultural upheaval and movement among coastal native groups. Some were pressured southward into the traditional territories of other native groups, others forced into slavery, and others enticed or coerced into Spanish missions. Some tried to resist, either by force, or by passive means, such as "visiting," rather than living at, missions to obtain food as the need arose. Successes were few and only temporary. In the case of Indians of the Rio Grande delta in the early 1500s, resistence to a Spanish expedition armed with cannons and crossbows is a remarkable story of strategy and wile —and was repeated successfully on three subsequent occasions. The Spaniards left, but, ultimately, others came in their place. Such was the case elsewhere along the coast. Native attempts to hold their lands were futile in the face of the larger, better-armed populations carrying trade goods and disease. During the Historic period, sickness and diseases brought by Spanish missionaries and French traders devastated entire villages. To cite only a few examples, the mission Atakapans were stricken twice by disease in the 1750s, while Karankawas suffered a "devastating scourge" of measles and/or smallpox in 1766. It was a gruesome story repeated across the region and indeed much of North America: disease, warfare, death, or assimilation. Within the course of just a few centuries, most of the coastal native societies were gone forever. In the following sections, we look first at the lesser known native populations of the lower coast, the peoples of the Rio Grande delta. From there we work upward to the Indians of the central coast—the Mariames and the Karankawa—and finally to the groups of the upper coast—the Atakapan speakers and Bidai In addition we provide extensive links to other resources on Texas Beyond History that feature data from Protohistoric, or early Historic, archeological sites in the coastal region. These exhibits provide a look at the physical traces left by the region's native peoples living during the time of early European entry, from tools and camp debris to ritual items and burials.In some cases, there are particularly tantalizing clues to interaction. In the Mitchell Ridge cemetery site on Galveston Island, for example, we see not only early Historic period European objects, such as glass trade beads and mirrors, intermixed with traditional native objects, but also provocative bioarcheologcial evidence suggesting interbreeding among native and European populations. In the case of La Salle's Fort St. Louis near Victoria, there is evidence that the Karankawa killed the French colonists in 1689 but subsequently lived and traded among the Spanish at the presidio built over the same site a few decades later. A number of archeologists and historians have specialized in the cultutural groups of the coastal region, and references to their work are provided below for further information. |

|

|

|

|

Signs of Trade and Transition. Native weapons, tools, and ornaments made of glass and metal provide tangible evidence of traditional technologies in transition, as Europeans began spreading their influence and goods across the coastal region. At left is a chipped-glass arrow point made from a Spanish wine bottle. Found in a Historic-period native campsite at Linn Lake in Victoria County, the artifact has been heavily weathered, causing the iridescent gold coloration known as patination. Photo by Bill Birmingham. Shown in center is a necklace of European glass trade beads strung together with native shell ornaments, found in an early Historic native burial at the Mitchell Ridge Cemetery on Galveston Island. Photo by Robert Ricklis. At right is a projectile point made from an iron keyhole escutcheon. It was found at the Shanklin site in Wharton County, along with a silver Spanish “piece of eight” coin and a quantity of chipped-stone tools and native pottery. Photo by Susan Dial, TARL Collections. Click to enlarge. |

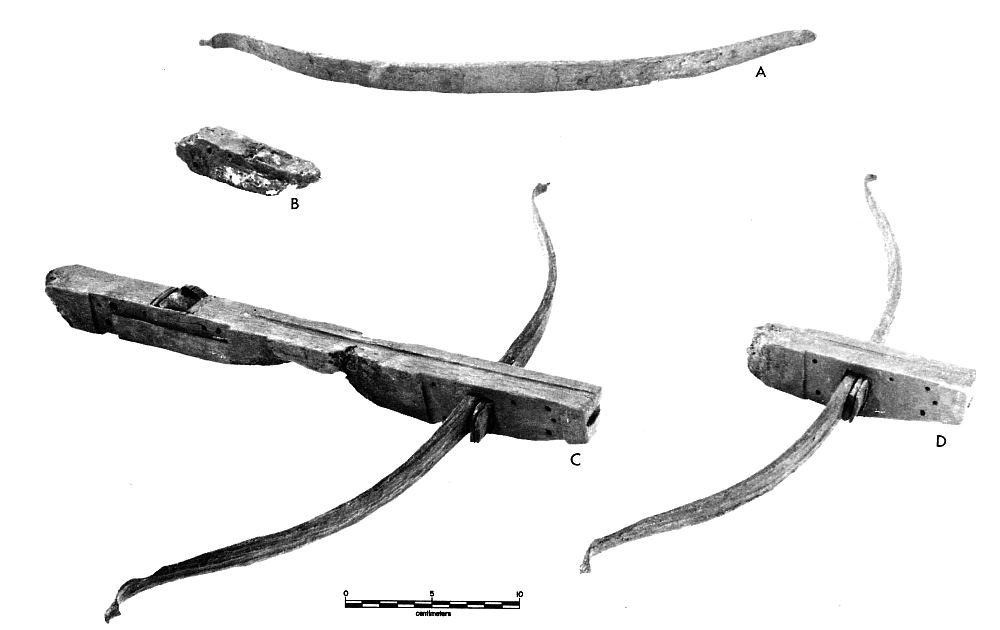

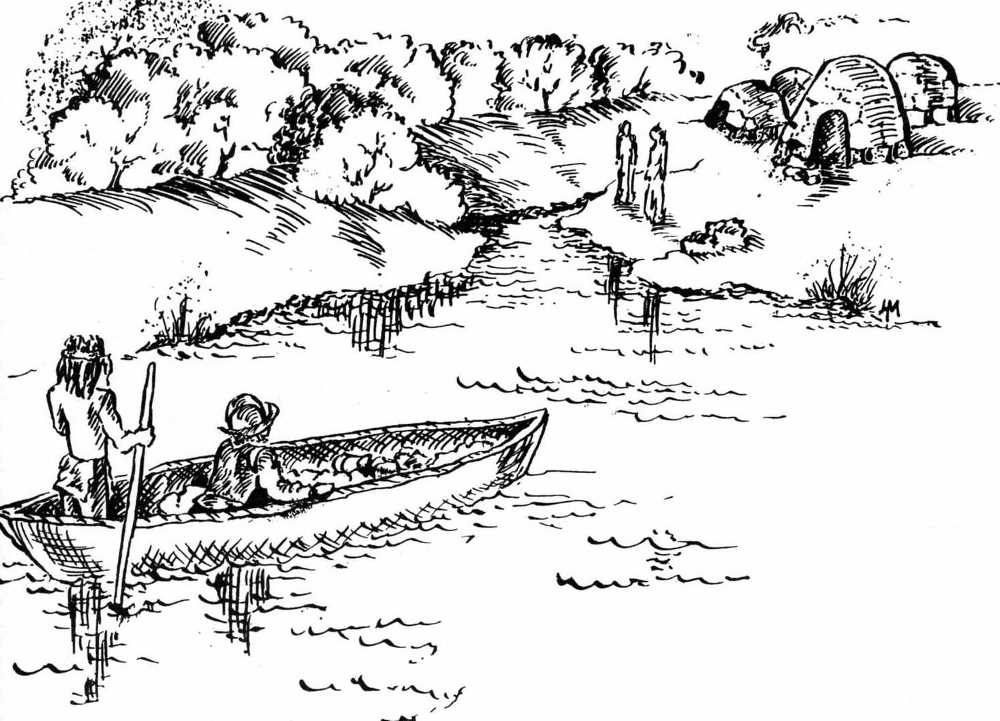

Peoples of the Lower Coast and Rio Grande DeltaWhen the waters of the Rio Grande reach their destination at the Gulf of Mexico, they have traveled over 1,800 miles from the snow melt high in the Rocky Mountains. Throughout their journey, these waters provided a rich environment for the native peoples who occupied the river’s banks. Teeming with fish, acting as a magnet for birds and wildlife, and giving nutrients to plants, the river offered a cornucopia of potential foods for the people who lived near it. Nowhere was that food more plentiful than at its mouth in modern Cameron County, Texas. Here, the Rio offered up not only the fish, wildlife, and a variety of plant resources as it did upstream, but, its mouth opened to a variety of salt water resources such as clams, oysters, and salt-water fish. The native peoples of the Rio Grande delta, like native people elsewhere in Texas, were knowledgeable about their environment and exploited the best of its resources when they were available. When those resources were not available, they survived by eating less nutritious foods, or by gathering their children and loved ones and moving elsewhere where other foods were could be found. There are few early accounts of native people living along this river's banks. From the archeological record, however, we know that the region had been occupied by native groups for thousands of years. Archeologists believe that during the early Historic era the region was well-populated by descendants of the prehistoric inhabitants, and this is borne out by historic records. However, not many sites dating to this time period have been recorded. A few sites, such as 41CF136 in Cameron County contain both native-made shell implements as well as a French musket gunflint and a thin piece of copper wire. These objects may represent contact with Europeans or recycling of discarded materials. Re-use of European goods is well documented in the region. In the 1750s, Spanish colonizer José de Escandón reported seeing a boat on the Rio San Fernando southwest of the mouth of the Rio Grande. Made from milled lumber, the boat had been fashioned from the remains of a French vessel and was being used as a fishing vessel by the Comecrudos, a local Indian nation. Why there are so few sites with evidence of European contact is somewhat puzzling, but may be attributed to interrelated factors. Compared to other regions, few sites have been excavated in the Rio Grande delta. Those that have generally show low densities of artifacts, perhaps making some archeologists reluctant to dig at sites with likely meager results. At the same time, numerous archeological sites have been eradicated in the crush of agricultural, urban, and residential development in the area. Consequently, the sites that are known may not accurately represent what was there in early Historic times. In contrast with the archeological record, the ethnohistorical record—documents, maps, and drawings—offers some hope for understanding the native peoples of the lower coast, although it too is less robust than desired. An excellent summary of the documentary record was published in 1990 by Martín Salinas. Intrigued by the native peoples who resided on both sides of the Rio Grande prior to the establishment of Texas, he researched Spanish, English, and French records, maps, and other documents dating prior to 1850 to learn about the original inhabitants of his native land. Early Spanish reports of expeditions mounted by Francisco Garay to assess the delta and its resources—including potential native laborers—provide glimpses of fierce local natives resisting in the face of European might. In the first expedition in 1519, four ships stopped at the mouth of the Rio Grande for 40 days. While there, an exploring party was sent up the river some 16 miles. In this exploratory effort the Spaniards counted 40 rancherías or encampments of Indians—a quantity that is relatively substantial for such a short distance. At first, the native peoples treated the light-skinned strangers as friends, or at least as equals who merited a polite greeting. As a result of this friendly reception, Garay, the governor of Jamaica, sent three more ships with 150 men, seven horses, and some artillery to the mouth of this same river. The Garay expedition, however, was not to merely explore the region more fully, but also to occupy the land along the Rio Grande. Sensing this change in intent, the natives made it clear that they were not pleased, and put into play a plan of their own. They mustered large numbers of reinforcements, likely accomplished by dispatching runners from one rancheria to another. Then, using canoes, the natives drove Spanish boats from the river. During the process, 18 Spanish soldiers were killed along with horses. Garay’s Spanish soldiers, recognizing that they were outmaneuvered, fled south by boat and by land. Accounts suggest that the attack was rapid, well planned, and did not allow the foreign intruders the means or time to counter-attack. The events are remarkable considering that the native weapons—bows and arrows—would have paled in response to well-aimed firings from the cannons on Spanish ships. The planning, the ability to bring together a large force, and the will to carry out their threat are indicators of the fierceness of the local native population and their attachment to their land. Two more attempts by Garay were met with equal effectiveness by the native peoples, first with another armed response, then with a well-planned disappearance into the brush country. Lacking natives to serve as worker bees for his colony, Garay decided to travel south to Mexican ports. His departure from the Rio Grande gave local native peoples nearly 200 years of peace from Spanish intrusions into the delta region. Groups with No Names? One of the curious aspects of early documents pertaining to the lower coast is that no names are provided for any of the rancherias or the native people themselves. This is unusual. In most expeditions, the Spanish either phonetically wrote down the names the people gave for themselves, or they arbitrarily assigned names to the people based on their physical characteristics, hair style or color, unique qualities of the physical place they lived, or some other unique characteristic. Yet, no names were assigned to the rancherias or native peoples encountered in 1519. In the mid-1600s, this trend of not naming groups changed—with a vengeance. Salinas discovered an abundance of native group names in the records for this period, but most represented groups who had moved to the Rio Grande delta after 1600. About that time, Spanish settlement began south of the Rio Grande in Nuevo Leon. By 1650, some 350 named Indian groups were recognized in that region. We do not know that they represented “tribes” per se. Some may have been small family lineages. Others may have represented villages. The names, however, were repeated in multiple Spanish documents suggesting that these groups had some permanency in the region. One of the facts that became clear to the Spanish during this period is that most of the groups in eastern Nuevo Leon were, or at least included among them, people displaced from regions to the west. These groups were generally hostile to the Spanish settlements and ranches and consistently raided them. In 1747, Jose de Escandón began establishing colonies in northeastern Mexico. In Texas, Escandón’s settlements were established on both sides of the Rio Grande, many of them in the area of modern Laredo (see Falcon Reservoir: Ghosts of Spanish Ranchos). However, he also established some settlements in Tamaulipas, just south of the Rio Grande. Documents associated with his initial settlements and subsequent inspections of these settlements offer more information on the native peoples who had moved into the Rio Grande delta region of the Lower Texas coast. From his reconnaissance of the region north and south of the Rio Grande in 1747, we learn the names of the then resident native groups, as shown in the table below. Groups are listed in the order encountered by Escandón, along with alternative spellings and pronunciations in Spanish. It is doubtful that groups listed in the same row shown in the table lived across the river from each other, but the listings give a sense of their distance from the mouth of the Rio Grande and the Rio San Juan. Some of these groups may have had remnants of the original inhabitants that Garay and his men encountered 200 years previously. While no population counts are available for groups living north of the river, Escandón puts the population of native peoples south of the river at 2,500 families. Perhaps a similar number existed north of the Rio Grande. Some names in the table were given Spanish equivalents. Masa cuajulam were said to be Los que andan solos meaning “those who walk alone. Paranpa matuju were called bemejos los hombres meaning “the men are red.” Salinas says this “may refer to skin color or, perhaps more likely, to male use of red pigment for body painting on special occasions.” Perpepug meant cabezas blancas or “white heads” in English, perhaps referring to the forehead. Peupuetem were said to be los que hablan differente meaning “those who speak differently.” Whether this refers to a different language or a unique accent is not clear. Segujulapem were said to be los que viven in los Guiachs meaning “those who live in huisache thickets.” Sepin pacam were said to be los salineros or the salt makers. There are several important saline lakes north of the Rio Grande, the largest known as El Sal del Rey. A number of sites have been recorded around the lake and likely represent efforts of local prehistoric and historic native peoples to exploit the rich salt deposits that are found on the soil around the lake. The Sepim pacam may have resided in the general vicinity of this lake. Comecrudos Three groups of native peoples were called Comecrudos in the 1700s, a term meaning “those who eat raw food.” Two lived south in Tamaulipas, but the third is associated with the Rio Grande delta. Salinas believes that is it unlikely that any of them were related. Their name appears to represent the Spanish characterization of their dietary habits. Those associated with the Rio Grande delta region may have been noted in some documents from the 1730s when there was a reference to raw food being consumed near the Rio San Juan. However, Escandón clearly noted them in his 1747 reconnaissance of the Rio Grande. At that time, they were led by a “Captain Santiago” (note the Spanish surname) who led other Indians in the region along with the Comecrudos. Escandón, camping near modern Matamoros, evidently asked him to bring other groups to visit with him. Captain Santiago did so via smoke signals, and some 200 families responded to the signals. They represented some 30 different groups then living in the area. Escandón stated that the Comecrudos, however, were the most numerous group among them. In subsequent years, life for the Comecrudos became harsh. They moved into Mission San Joaquin del Monte at modern Reynosa, Mexico around 1749. At that time they numbered around 150. By 1757, only 95 were listed in the census of the mission. They remained at the mission as late as 1886, but numbered only 25 by that time. Little is known about the daily lives of the Comecrudos, but we can infer some important aspects of their diet, clothing, and customs. Certainly, fishing was important to groups living along the Rio Grande near its mouth. In the 1680s Indians gave Spaniards fish, and Escandón reported that fish continued to be important to them in the 1750s. Salinas describes reports of bow and other types of fishing in the coastal lagoons of the mouth of the Rio Grande: “The Indians waded out into the water that was sometimes waist deep, quickly taking large numbers of fish." Another source noted that fishing was seasonal and that fish were dried and stored for later use: "Indians fished during the winter when foods were scarce….[L]ong nets [were used], made from soft yucca fibers with a mesh so fine that even the smallest fish were caught.” Wild plants were also important in their diet, particularly prickly pear tunas, mesquite bean pods, and maguey root crowns. Men were generally described as going without clothing. Women wore only skirts of animal skins or grass. Cabeza de Vaca and his companions, who had lost all of their European clothing after the shipwreck, found wearing native attire especially difficult; they often found themselves cold during the winters. By the late 1700s, both sexes were reported to wear skins or cloth clothing, likely an adaptation to Spanish influences. Many of the Rio Grande groups practiced tattooing. Whether the Comecrudos did is not known. Later travellers observed other adaptations among native groups in the area. In the 1830s, Jean Louis Berlandier, traveling along the Rio Grande during his expedition to Mexico, made note of small native groups such as the Garzas and Carissos [Carrizos] still living in somewhat traditional lifeways and linked by a common enmity toward Comanche raiders. The huts which form the outskirts of Mier are inhabited by a single tribe of indigenes known as the Garzas, who resemble the Carrizos in every way. All speak Spanish perfectly and besides have preserved their own particular tongue… The chief and his subjects…have not retained anything of a savage life, other than their nudity and a taste for travels in the forests. They go hunt in the forest to provide for their subsistence…. All these distinct nations—formerly savage and today reduced to living in society—preserve an implacable hatred of the Comanche, against whom they have sometimes waged war in favor of Mexican towns. Much has changed on the Rio Grande delta since the time when aboriginal peoples lived there. In 1519, Spanish explorer Alonso Alvarez reported that the river's mouth was more than 30 feet deep; he could sail his four large vessels some 20 miles up the river. Today the Rio Grande typically is little more than a trickle when it empties into the Gulf of Mexico. |

|

|

Peoples of the Central CoastThe central stretch of the Texas coastal shores and inland grassy plains was the domain of the Karankawa, the overarching name given to at least five distinct groups of native peoples who shared a common language and culture—the Carancaguases, Cocos, Cujanes, Guapites (Coapites), and Capoques. During the 16th and 17th centuries, these names were recorded, with numerous variations in spelling, by Cabeza de Vaca and other Europeans who encountered them as they traveled through the region. Farther inland lived the Mariames and other small groups whose names and cultures largely have been lost to history. Karankawa Historic maps depict the central coastal region and part of the upper coast, extending from Corpus Christi Bay to Galveston Bay, as the home of Wandering Tribes, and this aptly describes the Karankawa (and many other groups, as well). In a long-established and successful adaptive pattern—perhaps extending back some 3,000 years in time—Karankawa groups migrated seasonally from the mainland area to the coastal bluffs and barrier islands as resources became available. This mobile lifestyle was accomplished in part through use of dugout canoes in which fishermen plied the bays and estuaries and ventured inland along rivers and streams. Crudely built but sometimes large, some vessels reportedly accommodated entire families and their possessions in moving between camps. Each year, during the fall and winter months, groups of Karankawa familes gathered together in large fishing camps along the coast to harvest a variety of fish and shellfish, make tools, and other perform maintenance tasks. Their temprary homes were huts of thin poles, brush, and hide which could be easily packed and moved to the next camp. The cooler months are prime times to catch schooling fish such as redfish as they head into the deeper waters of the Gulf. According to historic accounts, fishermen used weirs placed at tidal passes to trap fish as they moved seaward. Based on archeological ebidence, we know they used a variety of other types of fishing gear as well —spears, bows and arrows, and even baited shell hooks—to procure a successful harvest. Shellfish, too, such as Rangia cuneata clams, oysters, and conch, were gathered from the muddy bottoms and banks of shallow bays and estuaries. These provided both food and hard shell to make into tools and ornaments. In spring and summer, the group split into smaller parties to hunt deer and buffalo and gather roots and fruiting plants in the coastal prairies. Based on archeological evidence from both coastal and prairie sites, Karankawa territories appear to have extended inland some 40 kilometers (roughly 25 miles) from the upper bays along the coast. Beyond this boundary, other native groups with quite different cultures and languages made their home, and it is likely that the various groups maintained trade relations, if not social networks. Karankawa bands were typically composed of some 30 or 40 people and were headed by "chiefs." Anthropologist Albert Gatschet, who became interested in the coastal natives in the late 1800s, found that the Karanakwa were led by two types of chiefs: one for civil government and one for war. Both roles were reserved for men. As in many other native groups of the time, women had a lower status and performed the most tedious tasks in camp. According to Cabeza de Vaca, their labors included erecting and taking down huts, cooking, and collecting firewood. The Karankawa were prolific pottery makers, crafting distinctive coiled-clay vessels known to archeologists as Rockport ware. Vessel types included large ollas used for holding water and perhaps dry foodstuffs such as seeds, as well as bowls and widemouth jars used for cooking and serving. The interiors of some pots were coated with asphaltum to seal and waterproof the container. The tar was also used to decorate vessels with dots, lines, and other designs and to repair cracks. Archeologist Robert Ricklis has studied similarities between prairie Karankawa sites and those attributed to the Toyah culture, which extended over a large swath of central and south Texas in Late Prehistoric/Protohistoric times. Both peoples used similar tool kits and are distinguished primarily by their pottery. Toyah folk made a thin-walled, bone-tempered pottery termed Leon Plain. A large number of archeological sites in the region have been attributed to the Karankawa (see the Guadalupe Bay and the Kirchmeyer exhibits). To learn more about the Karankawa, both in historic as well as prehistoric times, see the Ethnohistory section of the Mitchell Ridge site. The Fort St. Louis and Mission Espiritu Santo site exhibits provide more information on Spanish attempts to "Christianize" the Karankawa. The Mariames Unlike the Karankawa, the Mariames did not frequent the coastal bays or barrier islands. Instead they lived along the “River of Nuts”—the lower Guadalupe River— about 20 miles inland. They moved their camps every few days, probably going up and down the river through modern Refugio, Calhoun, and Victoria counties. Much of what we know about the Mariames comes from the accounts of Cabeza de Vaca. Traveling down the coast around January, 1533, Cabeza de Vaca found his lost companions, Dorantes and Esteban, at the River of Nuts living among the Mariames, and his other comrade, Castillo, living with their neighbors, the Yguases. For nearly two years, the Spaniards lived with these native groups, and their accounts provide a fairly intimate glimpse of how they lived. The Mariames were described as hunters and gatherers who “grind up some little grains with them [the nuts, i.e. pecans] two months of the year, without eating anything else, and even this they do not have every year, because one year they [the trees] bear, and the next they do not.” While its seems improbable that they ate nothing but pecans, ground or unground, for two months, it is likely that nuts dominated their food during the harvests. Cabeza de Vaca makes similar statements about their limited menu when the Mariames were in the tuna fields, harvesting the fruits of prickly pear cactus: “They eat them three months of the year, in which they eat nothing else.” We also learn that Cabeza de Vaca was not fond of their staple food—plants roots and bulbs. Their food supply is principally roots of two or three kinds and they look for them through all the country….They [the roots] take two days to roast and many of them are bitter, and on top of this is with great labor that they are dug out. It’s not clear if the Mariames ate these roots because they preferred them or out of necessity. Cabeza de Vaca makes it clear that the Mariames and other native groups did not always have adequate food to eat, saying that they moved their camp every two or three days to look for food. So great is the hunger that those people have that they cannot do without them [the roots again], and walk two or three leagues looking for them. Sometimes they kill some deer, and at times, they take some fish. But this is so little and their hunger so great that they eat spiders and ant eggs and worms and lizards and salamanders and snakes and vipers that kill the men they bit, and they eat earth and wood and whatever they can get, and the dung of deer and other things which I refrain from telling, and I believe truthfully that if in that land there were rocks, they would eat them. They keep the fine bones of the fish that they eat and of the snakes and other things, in order to grind it all later and eat the powder from it. Although he does paint a picture of a people who sometimes went without food, he notes elsewhere that “all these people are archers and well built,” suggesting that they were not starving or emaciated. On their trek to the tuna fields, they did not have food for several days, but the Mariames did not seem discouraged. They, to cheer us up, would tell us not to be sad, that soon there would be tunas and that we would eat many and would drink their juice and would have our bellies very big. The Mariames’ outlook on life is detailed further: “They are very happy people; no matter how hungry they are, they do not stop dancing or performing their celebrations and songs. For them the best time that they have is when they eat the tunas, because then they are not hungry and all the time they spend dancing, and they eat them night and day all the time that they last.” Life for Mariame women, however, may at times have been quite difficult. Cabeza de Vaca’s accounts indicate that the only women among the Mariames were adults, and there was a reason for this. Brides were never selected from within the Mariames or Yguases groups. They were always obtained from their enemies by trading their best available bows or, if that was not possible, a net for the brides. If the union produced a female baby, it was killed. When asked why they did so, the Mariames said: “because all those of the land are their enemies and with them they have continual war, and if by chance they should marry their daughters their enemies would multiply so that they [the Mariames] would subject them and take them for slaves.” The purchase of brides from enemies suggests two things. First, enemies are regarded as powerful people on the horizon: people to be feared, people to watch out for. They may have other qualities—mean, cruel, ugly, terrible—but by definition an enemy is someone with the power to hurt you or your kin. If they did not have this power, they would not be feared and not an enemy. Therefore, a bride who comes from such a fearful group would be expected to bear male children who would be as powerful as the enemy. Yet, brides reared and taught by the enemy may have a darker meaning: can they be trusted? There is nothing overt in Cabeza de Vaca’s narrative to suggest that the Mariames women were untrustworthy. There are hints, however, that women’s status within the society was quite distinct from the status of men. He states that marriages “do not last longer than they are content and for a trifle they undo the marriage.” The “they” in this passage appears to refer to the men. Men, then, had the right to dissolve marriages, but women did not. When it was dissolved, it is not clear what happened to the woman. Mariame women were described as hard workers and carried most loads: “The men do not carry loads, or anything of weight, but the women carry it and the old, who are the people that they regard least.” It is not entirely clear, but this passage seems to say that not only do the women carry most loads, they are also only one rung up the status bar from the old “who are the people that they regard least." He relates further: Mariame men had the job of hunting, and Cabeza de Vaca notes they were capable of running all day in pursuit of a deer. They also often hunted in larger groups, using torches to herd deer into groups and dispatching them within the circle. Using this strategy—hunting in a surround—they reportedly could kill 200-300 at a time on occasion. Often, as not, however, none were killed, and hunters (or the women and children) depended on trapping rodents. More about Cabeza de Vaca’s life among the Mariames and other south Texas groups is presented in the TBH exhibit, Learning from Cabeza de Vaca. Peoples of the Upper CoastThe upper coast was home to the Akokisa, Bidai, and other smaller groups of Atakapan speakers, whose territories bordered those of the Karankawa (Cocos), the Caddo to the north, and Southeastern groups to the east. It is believed that the Akokisa and Bidai shared a common linguistic and cultural tradition with the Atakapa of south-central and southwestern Louisiana. The Akokis and Bidai are assumed to have spoken a Western Atakapan dialect, while the peoples living in the Lake Charles area of Louisian spoke an Eastern Atakapan dialect. Some have suggested that the eastern and western groups spoke their own language in addition to a common second language. Unfortunately, so little is known of the Atakapan language family that the precise linguistic relations may never be known. Archeologist Lawrence Aten believes the historically known Atakapan-speaking tribal groups are part of the Mossy Grove culture pattern that extended over a large swath of the upper coast and prairie region from southwestern Louisiana to roughly the Brazos River in Texas. Aten holds that the ancestors of the Akokisa and the more inland Bidai shared for an extended time period—perhaps as long as 2000 years—many cultural, technological, and linguistic similarities that were fairly distinct from surrounding ethnic groups, such as the Hasinai (Caddo). Coastal Mossy Grove peoples and their descendants appear to have been hunter-fisher-gatherers whose subsistence was based on game, fish, wild plants, and shellfish taken from in and around the estuaries, bayous, lagoons, and bays along the upper coast. These long-established subsistence patterns as well as traditional territories slowly began to change as Europeans came into the country, with influences and disease transmitted in advance of their actual entry to the region. Shipwrecked Europeans, including Cabeza de Vaca and the Frenchman De Bellisle, arrived on the upper coast, but remained only until they could escape or move to another native group. Their presence may have had little impact on local peoples, but their accounts provide remarkable insights into day-to-day native life. Cabeza de Vaca, shipwrecked in 1528 on what was likely Galveston Island, describes being found by a handful of natives carrying bows and arrows; within a half-hour, he was captive in an armed group of more than 100. According to his accounts, the native peoples were dependent on marine and terrestrial resources of the island in fall and winter months (fish, roots, and rats) and staples of the mainland and estuaries (deer, small game, rangia clams, berries and other plant foods) in the spring and summer months. As was the case for Indians of the central coast, this dual mobility strategy at times involved the use of dugout canoes to travel across deep water and gain access to many bodies of water with soft muddy bottoms that very difficult to cross by foot. Likewise, while barrier islands are relatively large land masses easily visible from the mainland, are often separated by bay areas and tidal passes that are difficult to cross without boats. Other than the few hapless visitors, native groups of the upper coast had very little contact with Europeans until the 1700s, after which time the region increasingly was the scene of intense rivalry between the French and Spanish who vied for control of trade with native groups. The vast territories of New Spain and French Louisiana met along a border in the Sabine Lake area of Texas. Rumors of incursions by the French into New Spain, such as the ill-fated La Salle Colony in 1689, had prompted the Spanish to send a series of expeditions along the Texas coast as far north as Galveston Bay. The Spanish found substantial reason to be concerned about their interests in the area. In the 1720s both the Bidai and Akokisa (Orcoquisac) were participating in an illicit trade relationship with French traders. In exchange for deer hides, furs, and bear grease, they received a variety of European goods, including guns, brought from New Orleans. To deal with this encroachment, the Spanish government began establishing a greater presence in southeast Texas. In 1756, the Spanish established a presidio and mission for the Akokisa on the east bank of the Trinity River, a site they called El Orcoquisac. Although this establishment served to hamper trade with the French, the Spanish were less successful in forming their own relationships with the Indians. A planned civil settlement in the area failed to develop, and in 1766 a hurricane devastated the mission and presidio. The Spanish ultimately broke their trade agreements with the Bidai when it was learned that they were providing French firearms to the Lipan Apache and involved in other alliances detrimental to the interests of New Spain. Ultimately breaking up into small bands, the Bidai were devastated by epidemics, and by the middle of the 19th century, there were few remaining. Those who survived joined other groups. Remnant groups of the Akokisa population remained in their traditional homeland into the 19th century. However, as Anglo-American settlers moved more aggressively into the region, surviving Akokisa moved inland to join the Bidai. Based on remarkable documentary evidence uncovered by archeologists Roger E. Moore and Madeliene Donachie, a few Akokisa/Bidai individuals who spoke the Atakapa language still lived in small groups in Harris County as late as the early 20th century. They resided on land along Cypress Creek homesteaded by Matthew Burnett in 1836. Burnett’s daughter, Rebecca Burnett Lee, wrote a recollection of her early life that included details about the Indians who lived there, including a description of a chief named “Francisco”. Chief Francisco presided over a Bidai dance held at a pavilion of bark apparently erected for the occasion. She recalled Chief Francisco playing music on an instrument consisting of stretched alligator hide over which a small stone was rubbed, producing a “honk-honk” sound. Mrs. Lee’s recollections were independently confirmed by the subsequent owner of the homestead, Chester Telge. Mr. Telge’s family bought the land from the Burnett’s in the 1850s. He was born there in 1918 and the Bidai were still living there in hide tents on pimple mounds. Mr. Telge told Moore and Donachie that: Coastal archeologist Robert Ricklis has written a more-detailed ethnohistory section covering the natives of the upper coast in in the TBH exhibit on the Mitchell Ridge site. Viewers are referred to that section as well as the site of French trading post and Spanish missions known as El Orcoquisac for more information on interactions between upper coast natives and Europeans. CreditsThe native Peoples section was written by Nancy Kenmotsu and TBH editor Susan Dial. Kenmotsu holds an M.A. from the University of Colorado and Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin, where her doctoral studies focused on the native peoples of the Junta de los Ríos region of west Texas. Formerly director of Cultural Resource Management at the Texas Department of Transportation, she is now works for Geomarine, Inc. Kenmotsu and Mariah Wade are co-authors of Amistad National Recreation Area: American Indian Tribal Affiliation Study, An Ethnohistoric Literature Review SourcesAten, Lawrence A. Berlandier, Jean Louis Campbell, T. N. Foster,William C. (editor) and Johanna Warren (translator) Gatschet, A.S. Jackson, Jack, W. Weddle, and W. DeVille Kennedy, Skip, and Jim Mitchell Kenmotsu, Nancy A., and Mariah F. Wade Krieger, Alex D. Mercado-Allinger, P. A., N. A. Kenmotsu, and T. K. Perttula Minet Newcomb, W.W. 1984 The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times. University of Texas Press, Austin. 1983 Karankawa. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 10, Southwest, edited by Alfonso Ortiz: pp. 359-367. Smithsonian Institute, Washington. Olds, Doris Ricklis, Robert A. Salinas, Martín Weddle, Robert (editor) |

|