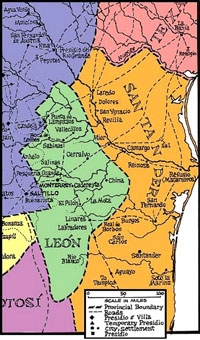

Area of Nuevo Santander. Adapted from map

by Jack Jackson.

|

=Image can be enlarged =Image can be enlarged

|

Mexican cowboys branding cattle in south Texas, early 1900s. The roots of the cattle industry, and Texas' rich ranching heritage, can be traced back to Spanish Colonial days. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission.  |

Because of the continual threat of raids by hostile Indians, many of the early ranch homes were built as fortress-like compounds. Shown is the Trevino fort constructed around 1820 at San Igncinacio, south of Laredo, Texas. This National Historic Landmark still stands, and the complex is open to the public. Historic American Buildings Survey Photo, circa 1920.  |

|

Throughout the eighteenth century, the Spanish made expeditions

into the area we now call Texas to set up missions and presidios

(military forts). They were designed to convert the native inhabitants

to Christianity and to maintain a presence on the land they claimed

for Spain. San Antonio also became an administrative center for

the area, growing into a town that housed military leaders and government

officials as well as artisans, ranchers, missionaries, Native Americans,

slaves, and servants. However, before the mid-eighteenth century,

there were no Spanish settlements that were made up of just civilian

families who made a living off the land. That was soon to change.

In 1748, José de Escandón led a Spanish

expedition to colonize the Province of Nuevo Santander. This was

a portion of land uninhabited by the Spanish at the time. Located northeast

of Nuevo Leon along a portion of the Gulf of Mexico, it incorporated

lands between the Nueces River and the present-day boundary of Tampico, and included the southernmost portion of the Rio Grande. The expedition was to

be the first civilian-only settlement in Texas. The colonists were

farmers and ranchers, who moved north to try to build a new and

better life. The techniques and equipment they brought with them

became the standard for ranching operations in Texas and the West

well into the twentieth century.

Although stories of these early ranchers have been

passed down through the centuries to their descendants, relatively

little has been written or published for a wide audience. There

is a wealth of historic records in small archives such as courthouses

and family collections, but these handwritten documents are often

difficult to read and translate.

The area's first settlers, however, did leave tangible

information in the ground, some of which was recovered and studied by archeologists. For example, archeologists from the University of Texas

managed to excavate one of the rancho sites in 1950 and 1951 before it was completely

destroyed by the creation of Falcon Reservoir. From the structural

ruins and household debris emerged a poignant glimpse of day-to-day

life in the Spanish Colonial borderlands. It was the first rancho

excavated in Texas.

The following sections on the Falcon Reservoir area trace the area's settlement, with a detailed look at the Leal rancho and the information recovered from archeological investigations. We also look at the area after the innundation of Falcon Reservoir and the toll taken on on archeological sites

as the waters periodically rise and fall.

This exhibit is the first of several in the region we hope to provide on Texas

Beyond History. In the future, we hope to trace personal stories of the inhabitants through oral histories and explore the rich

architectural legacy that still survives in the region's small towns

and rural areas. We will also look back at some of the structures

that have been lost to time and modern development.

|

Stone structures from eighteenth-century

ranchos stood in ghostly ruin before they were submerged beneath

the waters of Falcon Reservoir in the 1950s. Before the inundation,

archeologists documented several sites, capturing much information

that otherwise would have been lost. Photo by Jack Humphreys,

from TARL archives.  |

|

The techniques and equipment the colonists brought with them became

the standard for ranching operations in Texas and the West

well into the twentieth century.

|

Archeologists from the University of Texas at Austin unearth the floor of a Spanish Colonial ranch house in Starr County. This excavation and others conducted during the early 1950s provided a wealth of information about early ranch life on the border. TARL Archives.  |

|