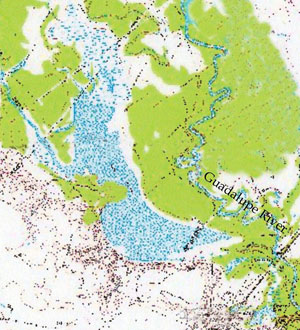

Native campers frequented the shores of Linn Lake in early Historic and earlier times. Today, the small inland lake is dotted with the skeletons of trees killed when logjams on the Guadalupe River caused water levels to rise. Photo by Bill Birmingham. |

Linn Lake

The shores of Linn Lake once were lit by the small campfires of hunters and gatherers drawn to the area's rich array of resources. In early historic times, these native peoples—perhaps offering deer and bison hides processed at one of their camps—traded with Spanish soldiers and settlers at nearby missions and presidios.

Located not far inland—roughly 20 miles (32 kilometers)—from the San Antonio Bay system and its marine resources, the natural inland lake is fed by the waters of the Guadalupe River. Linn Lake formed in a meander channel of the river that was "abandoned" when the river changed course sometime in the past. The water level in the "oxbow" lake has changed periodically over the years, resulting in the exposure of a number of the native campsites.

Between 1960 and 1980, a series of log jams on the lower Guadalupe River caused the water to back up the river, raising water levels roughly 6 to 8 feet above flood stage. Thousands of acres of bottom land were flooded, and the waters in Linn Lake rose 5 to 6 feet above their normal levels. The sustained high water levels lasted for years, killing very old trees and exposing, by wave action, the native campsites along the lake.

At this point, the sites could have been destroyed by natural processes or picked over by artifact collectors, resulting in loss of evidence and context. Instead, the subsequent story was one of discovery, careful documentation, and periodic monitoring as more of the sites was revealed.

In the 1970s, the Linn Lake landowner called in Victoria resident Bill Birmingham, Archeological Steward for the Texas Historical Commission, alerting him to the quantities of clam shells, flint flakes, and other artifacts that were eroding along the lake's edge. After the log jams on the river were broken up and water levels dropped, area resident Sonny Timme informed Birmingham of other artifacts from Linn Lake, including several arrow points and pottery sherds. Along with another interested avocational archeologist, Don Will, the group took notes on four sites (41VT80, VT81, VT82 and VT84), filled out official site survey forms, and filed the documents with the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory.

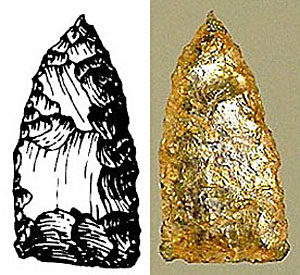

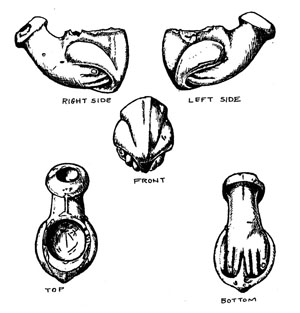

Over the past 25 years, Birmingham and others have continued monitoring the sites, conducting "salvage archeology," screening sediment from the wave terraces, and collecting artifacts as they are exposed on the shore. The artifacts are inventoried and documented. They have inventoried a wide range of artifacts, ranging in age from Late Archaic to the early Historic Period, including flake tools, thin blades, scrapers, bifaces, cores, Scallorn, Perdiz, and Cuney arrow points and Ensor and Palmillas dart points, knives, bone awls, deer and bison bone, gar scales, and Rangia cuneata clam shells. Marine shell artifacts have been found at all four sites, including conch shell adzes and pendants and columella gouges. Hundreds of pottery sherds have been recovered, and Birmingham has painstakingly reconstructed many of these to form several almost complete vessels.

The Linn Lake sites were the focus of a week-long field school session for students from the University of Texas at San Antonio directed by Dr. Thomas R. Hester in 1985. The students uncovered a quantity of lithic materials, including Fresno arrow points, as well as animal bone, such as domesticated pig, further indications of early Historic occupation.

Several aspects of the Linn Lake evidence point to trade networks or broader contacts among peoples, both Indian and Europeans, during the early Historic Period. Birmingham notes that in the southeastern area of 41VT81, a number of Cuney arrow points, end scrapers, and pottery sherds were found. Cuney points are typically found in sites from the Early Historic period in East Texas, associated with the Allen phase and Hasinai Caddo. Also found on the eroded surface at the same site was a glass Guerrero arrow point, thought to have been chipped from a green wine bottle of probable Spanish Colonial age. The thin, stemless Guerrero points are the hallmark of the Mission period, and were made by native peoples in mission settings as well as in more traditional campsites.

Most recently, Birmingham collected 30 pottery sherds from 41VT82 that, remarkably, fit a previously restored partial vessel which he had found some 25 years ago. The vessel, of a Coastal Bend type archeologists term Rockport Black-on-Gray, is decorated with an incised, crenelated rim. Rockport pottery ranges in color from dark gray and brown to buff or reddish brown, as is illustrated in the examples shown here. Birmingham believes that the unusually large size of the sherds, and the fact that many were found in dense clusters, indicate the site has been relatively undisturbed since the vessel was used and left behind (perhaps broken) by native campers several hundred years ago. In many sites, later campers trampled and "overprinted" the remains left by earlier peoples. Pottery found at such sites is typically broken into hundreds of tiny pieces.

Birmingham plans to continue his periodic monitoring of the Linn Lake sites and others in the region. He has curated the artifacts at the Museum of the Coastal Bend in Victoria, where interested researchers now will be able to study them and fully interpret the findings. A former regional Vice President for the Texas Archeological Society, Birmingham's interest in archeology spans decades, marked by increasing awareness of the need to document and record finds. He recalls collecting "arrowheads" as a boy, and trying to keep track of them until he realized he "had so many he could no longer trust his memory." At that point, he says he began numbering and mapping surface finds, mentored by longtime area avocational archeologist E. H. "Smitty" Schmiedlin, and later by anthropology professor Thomas R. Hester. He has been instrumental in the discovery, documentation, and proper archeological investigation of many significant sites in the Victoria area including Johnston-Heller, Blue Bayou, J-2 Ranch, and Burris Bison sites and has collaborated with many appreciative professional archeologists. Today Birmingham hopes to continue educating collectors about the "lessons that can be learned from artifacts," and how much history is lost when "artifacts are picked up and put away, unlabeled, in boxes, or sold in garage sales."

Credits: Some of the images for this section were provided courtesy of Annette Musgrave at the Museum of the Coastal Bend and Sonny Timme.