1710 |

Franciscan missionary Father Francisco Hidalgo writes a letter to the French Governor of Louisiana from his post at San Juan Bautista offering to introduce the French governor to Spanish merchants in exchange for the French supporting his unfinished missionary work in east Texas. In the 1690s, Father Hidalgo had been in charge of failed Spanish missions to the Tejas Indians (Hasinai Caddo) in east Texas, and he was having trouble getting the Spanish to support his return. It was not until 1713 when his letter reached the newly appointed French Governor, Antoine de La Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac. Governor Cadillac told Canadian-born adventurer Louis Juchereau de St. Denis to go find Father Hidalgo, a seminal event that led to the establishment of Los Adaes. . |

1713 |

St. Denis establishes a French trading post on the Red River at what is today Nachitoches, Louisiana, so named for his Indian allies who were native to the area. St. Denis became a pivotal figure in the history of the area and of Los Adaes. At the invitation of the Father Hidalgo, St. Denis travels to San Juan Bautista

(see Gateway Missions exhibit), a Spanish presidio and mission on the Rio Grande, hoping to set up overland trade connections. Spanish Captain Diego Ramon arrests St. Denis and holds him for over a year, but the two become friends. In late 1715 or early 1716 St. Denis married María Manuela Sanchez de Navarro, Diego Ramon's step-granddaughter. This kinship bond between French and Spanish citizens would become a familiar pattern in Los Adaes history. |

1716 |

Domingo Ramon, son of Diego Ramon and uncle of St. Denis' wife, leads an expedition to establish missions across the Spanish province of Tejas (henceforth Texas). St. Denis is hired to guide the expedition. Over the next year the Spanish reestablish the original east Texas missions and four others including Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Ais, near today's San Augustine, Texas, as well as Mission San Miguel de Linares de los Adaes near present day Robeline, Louisiana. Mission Los Adaes lay within the territory of the Adaes Indians, a relatively small group who lived between the Red River and the Sabine River in what is today northwestern Louisiana. The small Spanish outpost was manned by a few soldiers and several padres. |

1719 |

War breaks out in Europe between France and Spain. This situation first becomes known to the Spanish in east Texas later that year when seven French soldiers from the Natchitoches post "attack" the Spanish mission in an amusing incident that has come to be known as the Chicken War. The French arrived unexpectedly and quickly captured the only Spanish soldier then present and began confiscating livestock and articles from the mission. Flapping chickens caused the French Lieutenant in charge of the raid to be thrown from his horse, allowing the lone Spanish lay brother then at the mission to escape and make his way to Mission Dolores. The news of the attack (and the war in Europe) cause the Spanish in east Texas to again abandon their east Texas missions and Presidio Dolores and retreat to San Antonio de Béxar. |

1721 |

Truce is declared between the Spanish and French. The Spanish governor of the Province of Texas, Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo, leads a major expedition to reestablish the east Texas missions. The renamed Mission San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes is rebuilt a few miles to the east of its original location on a low hill or ridge overlooking a small spring-fed creek and flat terrain thought to be suitable for agriculture. Aguayo leaves behind a contingent of 100 soldiers, 31 of whom were accompanied by their families.

Over the next few years the soldiers build Presidio Nuestra Seora del Pilar de los Adaes to safeguard the mission and defend the province from the nearby French. Lacking building stone, the presidio and mission are built of pine and hardwood timber, materials that deteriorate rapidly in humid conditions. Decay, repair, and rebuilding were to be constant features throughout the history of Los Adaes. |

1720s |

For sustenance the Spanish soldier-settlers and the missionaries at Los Adaes depend on supplies brought overland on horse and mules from New Spain. The Adaeseños, as the inhabitants of Los Adaes came to be known, are joyous at the arrival of maize, wheat flour, and cattle and sheep sent by Governor Aguayo in the fall of 1721, an event that historian Robert Weddle described as "the forerunner of the cattle drives which were to play such an important role in the later history of Texas." But Spanish supply convoys and livestock drives are few and far between, often delayed for weeks and months by flooding along the many rivers and major streams draining the coastal plain of Texas. The Adaeseños have to provide for themselves by farming and ranching. Repeated attempts to grow maize are met with only modest and irregular success, owing to the area's propensity for periods of excessive rain as well as summer drought. They fare far better at raising livestock.

To survive at Los Adaes the Spanish soon find themselves dependent on the French at nearby Natchitoches for food and supplies that they could otherwise obtain only sporadically. The Spanish have livestock and the services of their Catholic priests to offer the French. Although most trade with the French is officially prohibited, it is required for survival. Spanish authorities in New Spain periodically give the Adaeseños permission to trade for food, but illicit trade for food and other commodities become part and parcel of life at Los Adaes.

|

1727 |

Brigadier Pedro de Rivera is sent to inspect the presidios and missions of the Province of Texas. During Rivera's 11-day inspection at Los Adaes he observes no Indians living at the mission and sees little military reason to fear the French. Rivera's recommendations, to reduce troop strength at Los Adaes to 60 and close Presidio Dolores, are carried out in 1729. |

1729 |

The Spanish outpost of Los Adaes is officially designated the capital of the Province of Texas, although the Spanish governors have maintained official residences there since 1721. Los Adaes remains the provincial capital until 1770, yet only a few governors spend much time there. They frequently travel across the province and often stay in San Antonio de Béxar, which becomes a sizable settlement, closer to the core of New Spain. |

1731 |

Spanish soldiers from Los Adaes help the French and their Caddo allies at Fort St. Jean Baptiste (Natchitoches) repel a concerted attack by the Natchez Indians, a powerful Southeastern group then attempting to push westward into the Caddo Homeland. |

Mid-

1730s |

Already precarious conditions at Los Adaes reach an all-time low as severe weather, especially floods, cause repeated crop failures and long-delayed supply trains. |

1740s |

From 1741-1743 Tomás Felipe de Winthuisen serves as governor and cleans up Los Adaes, even-handedly enforcing regulations and carrying out a rebuilding program that repaired the presidio?s dilapidated palisade and buildings. In 1744 St, Denis dies and the new governor, Justo Boneo y Morales attends his funeral at Nachitoches. Spanish authorities are relieved at St. Denis? death, but the French remain strongly allied with their Caddo trading partners. |

1750s |

Under the lengthy governorship of Don Jacinto de Barrios y Jáuregui (1751-1759) trade with the French and Caddo-speaking groups becomes well developed, if mostly illicit. Hides (mainly deer) and tobacco become the accepted currency in the barter-exchange economy of the Louisiana-Texas frontier. The Spanish, French, and Caddo also become bonded by intermarriage and adopted kinship, such as compadrazco or co-parenthood. The commercial, political, military, and social links that the Spanish forged with their French and Caddo neighbors help maintain relative harmony, making Los Adaes the safest Spanish settlement in all of the Province of Texas. In contrast, large outposts like San Antonio de Béxar, are constantly threatened and raided by Apache and other Indian groups. Mission San Saba, which was built to serve and placate the Apache, is sacked and burned by an allied force of Apache enemies, including some Tejas, in 1758. |

1762 |

Near the end of the French and Indian War, which took place in upper North America, France cedes its holdings west of Mississippi to Spain. Fort St. Jean Baptiste becomes a Spanish fort, but French traders are allowed to stay as they were the mainstay of the local economy. |

1767 |

Watershed year that sees the best historical and architectural documentation of Los Adaes. The MarquZ¿s de Rub? visits Los Adaes as part of an official inspection of all of the presidios of the Spanish province of Texas. Joseph de Urrutia accompanies Rub? and draws a map of the presidio, mission and associated houses, agricultural fields, and roads of Los Adaes. Only two operable muskets, seven swords, and six shields are reported for 60 soldiers at Los Adaes. Rub? recommends that Los Adaes be closed. |

1768 |

Fray Gaspar JosZ¿ de Sol?s of the Franciscan College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas inspects all of missions of the Spanish province of Texas, paralleling Rub?'s political and military inspection. At Los Adaes, Sol?s finds no Indian congregation, a church building in disrepair, and church ornaments in very poor condition. He declares Mission Los Adaes a failure. Solís' diary is reportedly a good source of information, but its whereabouts are now unknown. |

1769-

1770 |

With failed maize crops and isolation by extreme flooding, Los Adaes is again in dire straits, its people facing starvation. The formerly French post at Natchitoches now flies the Spanish flag, but cannot provide food to Los Adaes because of shortages of its own. The Caddo-speaking groups are upset with the implications of the transfer of Louisiana from France to Spain because they have long been closely allied with the French and distrustful of the Spanish. At the same time Spanish authorities in New Spain feel the contraband trade networks could never be broken as long as Los Adaes remains an illicit waypoint. |

1772 |

Order is issued to close both the mission and presidio at Los Adaes and remove its citizens to San Antonio de Béxar. (The capital of the Province of Tejas had been officially moved to San Antonio de Béxar in 1770—the governor had moved there two years earlier.) Adaeseños resist the order and plead that they be allowed to stay in the place they cáll home. |

1773 |

Los Adaes is closed down and the residents are forced to leave abruptly. Over 300 residents move to San Antonio, but other Adaeseños apparently remain on outlying ranches or move into the surrounding area and ignore the evacuation order. Some Adaeseños drop out along the long trek to San Antonio, while others suffer horribly, losing property, livestock, and, in some cases, life. |

1774 |

Under the leadership of Antonio Gil Ybarbo, most Adaeseños leave San Antonio to return to east Texas, where they establish a settlement on the Trinity River: Nuestra Seora del Pilar de Bucareli. |

1777-

1778 |

Bucareli is abandoned as a result of Comanche raids and epidemics. |

1779 |

Adaeseños establish town of Nacogdoches. |

|

Artist?s depiction of Franciscan missionary Father Francisco Hidalgo writing a letter offering to introduce the French governor of Louisiana to Spanish merchants in exchange for the Spanish supporting his unfinished missionary work in east Texas. This letter would ultimately result in the establishment of Los Adaes. Image courtesy George Avery, original watercolor by Cornial Cox, copyright to Cornial Cox. |

The Destruction of Mission San Sabsÿ |

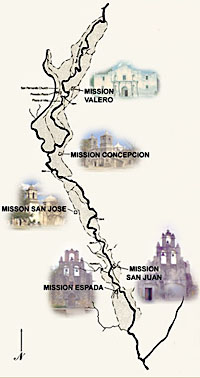

The missions of San Antonio |

|