What the Bones Say

|

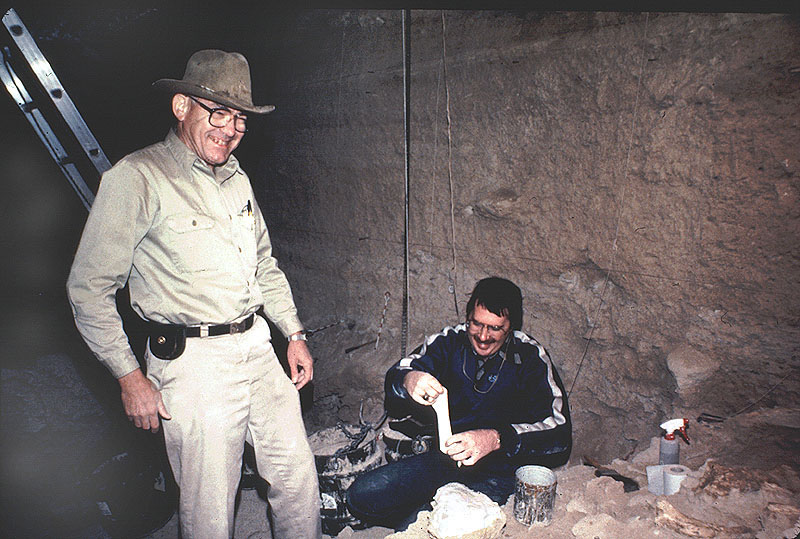

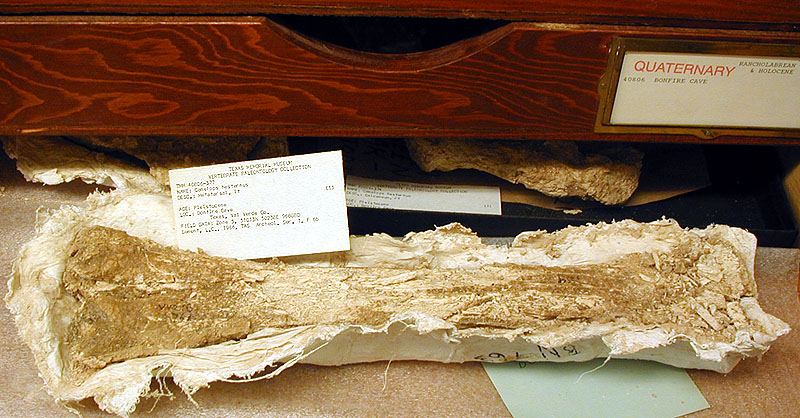

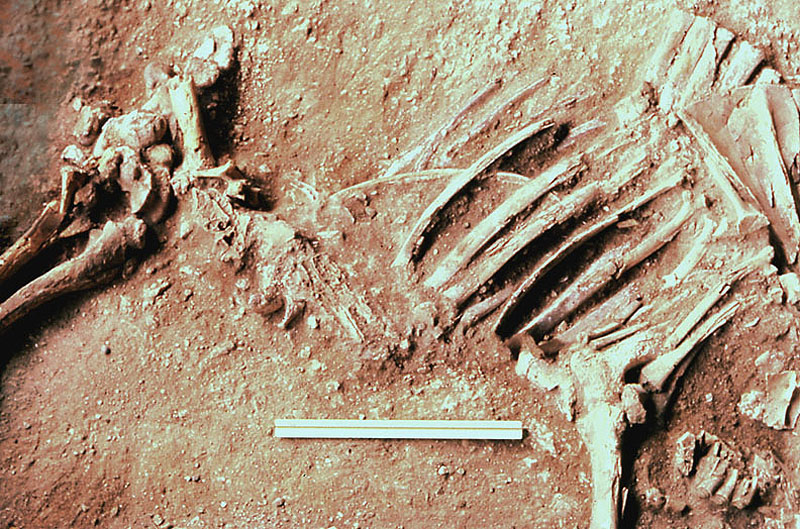

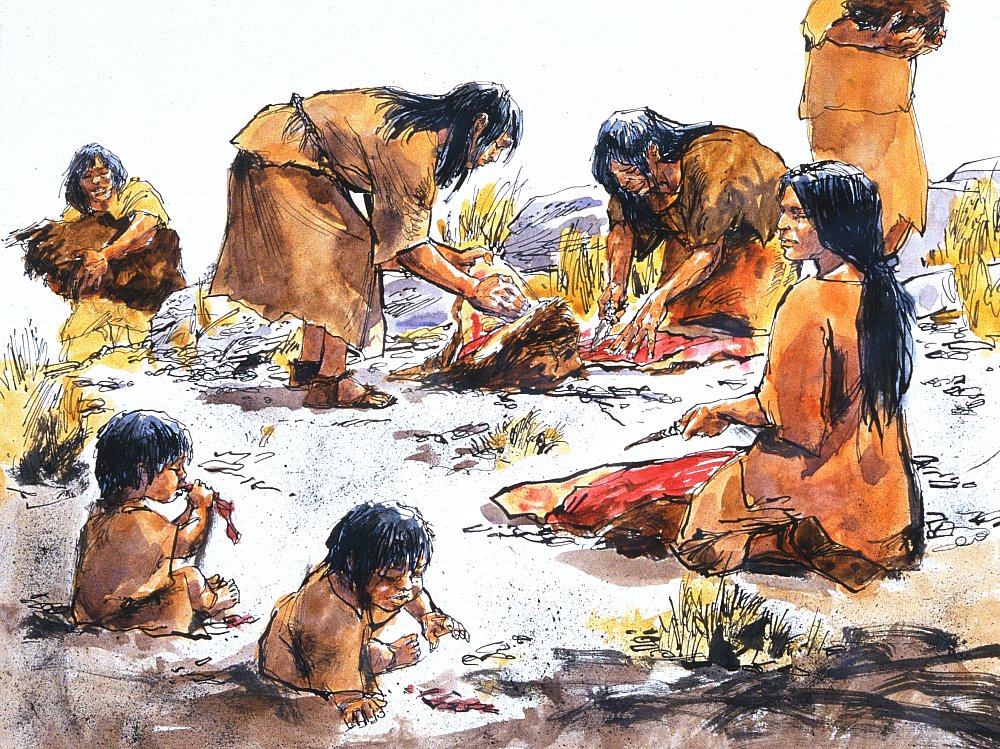

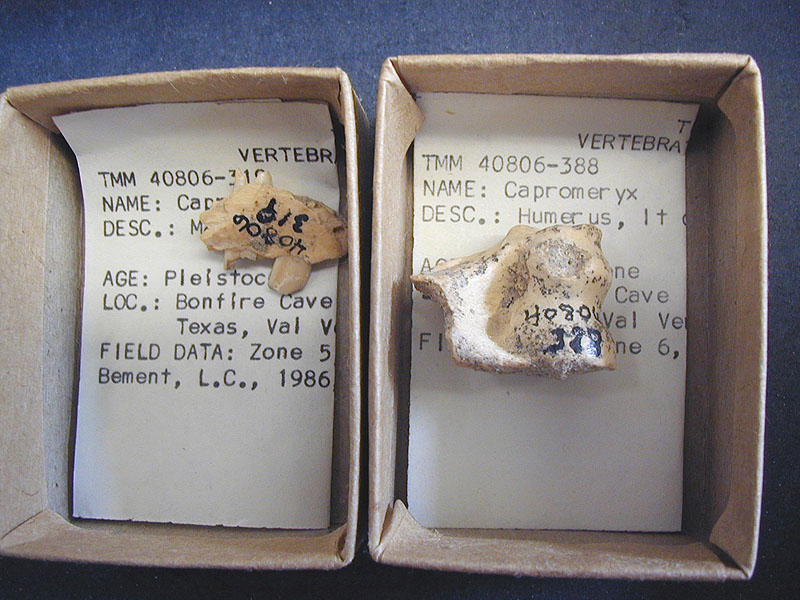

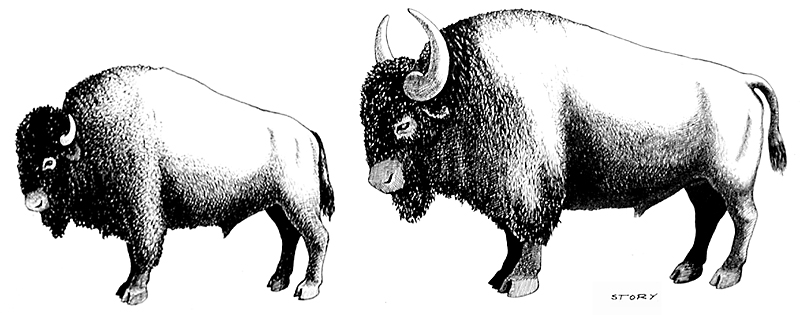

The thousands of bones that archeologists have carefully collected from Bonfire Shelter have quite a lot to say. If the bones actually could talk, they might be able to tell us fascinating things about the past including the details of how they came to rest where they were found. But they can't and so we must rely on faunal (animal) experts, archeologists, or paleontologists who develop specialized knowledge about animal bones, to study the bones and speak for them. What the faunal experts can tell us has a great deal to do with the kinds of questions they pose in the first place. Usually they start with basic questions—what animal is this bone from? Which specific bone element is this fragment a part of? But as they figure out the basics, they start asking more difficult "why" and "how" questions. How were the buffalo butchered? Why did the bones catch on fire? Regardless of the evidence we might muster to answer such questions, there really is not much in archeology that we can prove beyond doubt. We are usually dealing with the remote human past that left behind no eyewitness accounts, only mute bones and stones. What we can hope for, however, is greater insight and understanding. Although scientists may hold different opinions, it really isn't about being right; it's about trying to understand what the bones can tell us about what happened at Bonfire shelter. Below we look at some of the more-interesting things that have been learned from studying the bones and other kinds of evidence found within the bone beds at Bonfire. The BonesTwo "bone jocks," as faunal experts are sometimes known, have studied bones from Bonfire Shelter. Dessamae Lorrain studied the bones from the 1963-64 excavations, and Lee Bement, the bones from the 1983-84 work. Both took on the studies as their Masters thesis projects at UT-Austin. Lorrain had the advantage (and disadvantage) of working with a much larger sample and of being able to compare the Bone Bed 2 and 3 assemblages, but she did not participate (except briefly) in the fieldwork. Bement worked with smaller samples, but he was able to observe the bones firsthand as the fieldwork progressed and he could compare Bone Bed 1 with Bone Bed 2 (and BB3 for that matter). Both were guided by Dr. Ernest Lundelius, one of the foremost experts on Late Pleistocene fauna in North America, and former Director of the Vertebrate Paleontology (VP) Laboratory at UT-Austin. Today the excavated bones from Bonfire are kept in neatly labeled wooden drawers within the rows of metal cabinets that line the "big room" at the VP Lab. They are stored here for posterity (the future) because of their research value, awaiting one of several future uses. Sometimes the bones from Bonfire are used for comparative purposes—a researcher studying bison bones at another kill site might want to compare sizes, species, breakage patterns and so on. But their most important value is their potential to address new questions and provide new information. Perhaps the best example of untapped potential in the Bonfire collection is the microfauna—vial upon vial of tiny bones from rats, mice, gophers , birds, snakes, and other small animals. These bones were collected as part of a special set of soil samples from a column carved layer by layer from the side of one of the deep excavation pits. The bags of dirt were hauled back to Austin and then washed through fine mesh sieves that capture even the tiniest fragment. Then the hard part comes: someone has to spend hundreds of hours picking through each pile of bone fragments (and pieces of stone and other debris) to sort out the "wheat from the chaff"—or in this case, the identifiable bones from the miscellaneous fragments. What makes one bone fragment identifiable and the next one not? Experts look for distinctive features, especially whole bones and bone fragments bearing the intact ends of a bone, such as the ball joint where the femur (upper leg) fits into the hip (pelvis) socket. But telling the difference between the tiny femur of a pack rat and the tiny femur of a wood rat can be mighty tricky. The easiest bones to identify among the small animals are usually the teeth. Teeth are especially important because they are harder and more durable than most other bones, hence, most likely to survive the passage of time. Although the Bonfire microfauna collection has never been fully analyzed, it holds enormous potential to answer many questions. Here's one example: scientists know that small creatures are much more sensitive to environmental change than most large animals. While creatures large and small are equally affected by such drastic changes as the end of the last Ice Age, large animals like deer and bison are mobile and can survive smaller events—droughts and floods—just by moving. In contrast, mice and gophers cannot move very far. When climatic conditions gradually shift from wet to dry, small animal populations change in response; water-loving rodents die and over time are replaced by those that do well in the desert. By looking at the percentages of one kind to the other through time, these tiny bones can tell us a lot about how the local environment around Bonfire has changed. The microfauna are just one example of the continuing research value of the Bonfire bone collections. You might be wondering how all the rodent bones ended up in Bonfire. Most of the bones, it appears, did not go there of their own accord. Owls and hawks both eat a lot of small animals and like to roost or perch on high, protected spots like the top of the roof blocks at the mouth of Bonfire. These big birds eat the rodents whole, bones and all. The crunched-up bones (with many identifiable pieces) go through the bird's digestive system and end up as "pellets" on the floor of Bonfire shelter. These gradually break apart as they weather and the tiny bones become part of the cave sediments. The larger bones in the Bonfire collection have much to tell us as well. The most numerous, of course, are the bison bones. In the Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory are drawer after drawer of bison bones, each containing a different type of bone or several similar bones. Each drawer tells a different part of the Bonfire story. Bison feet bones are typically well preserved because they are relatively small and durable and because they are quickly discarded during butchering in favor of the meaty bones. Most of the feet bones were whole when found. In contrast, far fewer whole leg bones were found, and of those, most were the smaller ones. The larger leg bones are the main meat-bearing bones. The cavities within large leg bones, especially the femur, tibia, and humerus, are filled with marrow, which is full of fat and is, thus, highly desirable. While today many people try to avoid eating too much fat, the prehistoric Indians of the region had few sources of fat. Most meat is lean and contains little fat; the same is true for most plant foods (except nuts and seeds). So fat would have been craved, and fresh marrow is actually quite delicious. This explains why most of the leg bones from Bonfire are broken up, having had the marrow extracted by the prehistoric butchers. The skulls, too, are typically smashed, and the jaws broken apart. In this case, it is the brains and tongue that were being removed. Skulls were also broken up to remove the horns and horn cores. Bison horns were used in many dances and other ceremonies of later Plains Indians, and there is reason to believe that Paleoindians also placed special importance on bison skulls and horns. The most spectacular example is the now-famous painted bison skull from the Cooper site, a Folsom kill site in northwest Oklahoma that Lee Bement excavated. This skull had a red zig-zag emblem painted on the forehead and was apparently placed atop a pile of butchered bison bone as a ritual offering. (For details see Bement's Cooper web page or a special article in Current Research in the Pleistocene). Notice that bison bones from Bonfire show quite a range of color. (The glossy appearance is caused by wax, which was added in the lab as a preservative.) Some of the bones are black and charred, while others look like fairly fresh bone, while still others look bleached and weathered. These variations reflect where the bones came from in the deposits, how old they are, and how much time they spent on the surface before being covered by cave dust or more bones. Such factors also affect whether a given bone will be preserved at all or whether the bone surfaces preserve the evidence we need to figure out butchering and predator patterns. Many of the bones from Bone Bed 3 were so completely incinerated that they fell apart as soon as the archeologists tried to lift them up. Sometimes a special glue-like preservative was slathered on the bones to try to hold them together, but this messy process glued together dirt and ash as well as bone and was very time consuming. There were so many bones in Bone Beds 2 and 3 that the archeologists ended up having to concentrate chiefly on the intact and better-preserved pieces. Most of the very old bones from Bone Bed 1 were in poor condition. These required special coating with a penetrating preservative as a routine step, otherwise they would have crumbled apart soon after exposure. But this effort was worthwhile because it enabled archeologists to recover the bones of extinct animals including camel, horse, and mammoth. The Bone FiresBonfire Shelter witnessed two major bone fires or bonfires in its history; the really massive one that scorched and burned almost all of Bone Bed 3 about 2800 years ago, and a somewhat smaller fire in Bone Bed 2 at least 11,300 years ago. Both fires appear to be the result of cataclysms caused by spontaneous combustion as the steaming, rotting piles of partially butchered bison carcasses reached critical mass. The most spectacular and best-documented bonfire was that of Bone Bed 3, the fiery event that inspired the name Bonfire Shelter. Here is how archeologist Dave Dibble started his discussion of the matter in his 1968 report: A few facts regarding the burning of the bison bones became apparent during excavation: 1) the fire was a one-time occurrence rather than a series of blazes; 2) the burning occurred in place; (3) no evidence of fuel, charcoal or other (sic), was observed in the burned portion of the bed; and 4) the burning was sufficiently intense to oxidize virtually all carbon in the bones, reduce limestone spalls to powdered lime, and to shatter and glaze many of the chert artifacts included in the deposit. As a point of interest: the word bonfire has been traced back to the late 1400s when the terms banefyre and bone fyre described fires built of "clene bones and noo woode" in public celebration of certain saints (Oxford English Dictionary). While today the term is generally applied to large wood fires for public spectacle, inspiration, and celebration, the word's origin recognizes the obvious: bones are full of fat and will burn quite readily when heaped up. And it need not take a spark or match to ignite; decaying mounds of bone, hide, hair, and flesh give off gas and can build up tremendous heat, just like a pile of oily rags, and can burst into flame spontaneously under just the right conditions. Modern slaughterhouses are said to be well aware of this possibility and avoid creating heaps of bones and debris as a safety precaution. Fires lasting weeks or months are recorded from the cattle-trail boneyards that formed at slaughterhouses and railheads upon the Great Plains in the late 1800s. Dibble cited several other bison jump sites in the northern plains that also had extensive deposits of charred bones, suggesting that the Bonfire Shelter bone fires were not unusual occurrences. Not unusual, perhaps, and explainable, but the Bone Bed 3 inferno must have been quite the spectacle for anyone near Mile Canyon at that time long ago. It started with a tremendous boom as the built-up gases literally exploded and the concussive sound waves ricocheted off the shelter walls and up and down the steep-sided canyon. The flames may have burned for days, sending up greasy black smoke surely visible for many miles. And what the eye missed, the nose would detect. One imagines what the locals must have thought before connecting the unbidden blaze to the even more remarkable event—the unprecedented massive bison kill that had occurred many weeks or even months before. All this is speculative, of course, but it is probably not far short of the fiery mark. Even today, some 2800 years later, the evidence of the last bone "fyre" is still plain to everyone who climbs up to the shelter; what the blind eye might miss, the crunching bones underfoot reveal. The BisonThere were bison bones in all three of the bone beds. The bison bones in Bone Beds 1 and 2 were those of an extinct species, either Bison antiquus or Bison occidentalis, while the Bone Bed 3 bones were all of the modern buffalo, Bison bison. The best way of determining the species of extinct bison is to look at intact skulls, but none were found in either deposit. Faunal analyst Lorrain compared a variety of measurements of specific bones from Bone Bed 2 such as the width of the distal (lower) end of the tibia (upper front leg) to the same measurements from Bone Bed 3 specimens and those from bison samples at other sites. While she wasn't able to answer the question of species, she did demonstrate that the mature adult bones of the extinct bison at Bonfire were at least 12-18% larger than those of the modern bison. Taking other comparative studies of bison species measurements into consideration, the extinct species at Bonfire was at least 15% larger than modern bison. In more concrete terms, a large modern bison bull can weigh as much as a ton (2,240 pounds) and stand 6 feet high, while the adult males of Bison antiquus may have weighed as much as 3,500 pounds and stood 7 1/12 feet high according to Dr. David Meltzer, archeologist and Paleoindian expert at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. From the mindset of a hunter, imagine a full-grown modern buffalo, add a foot or two, and consider the courage it must have taken to get up close to an Ice Age bison and wave a spear or a blanket in its face. The Bone Bed 3 Animals and their ButcheringSuccessful hunters carve up bison into manageable

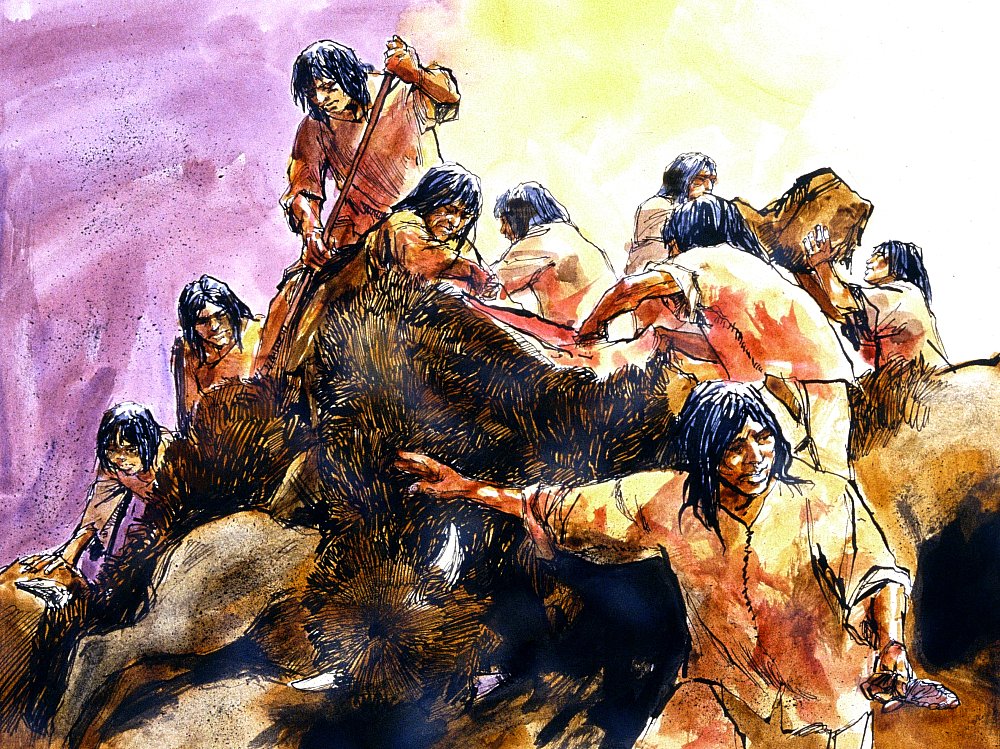

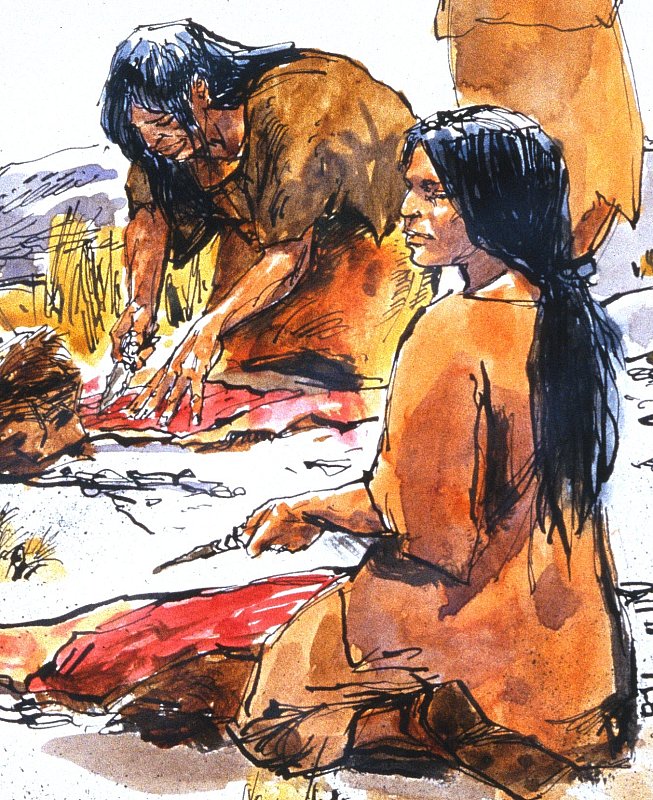

parts, separating front and hindquarters and the heads. Drawing

by Charles Shaw.

Lorrain estimated that there were bones of 800 bison in Bone Bed 3, mainly cows (adult females) and yearling calves. The absence of adult males and the relative uniformity of the age of the calves led her to argue that Bone Bed 3 formed as the result of a single event that occurred during the late winter or early spring. Dibble had trouble accepting Lorrain's single-event argument and so have other archeologists familiar with the site (including this author). The mass of bones in Bone Bed 3 more likely is the result of multiple jumps that occurred over a relatively short period of time. This debate is discussed in more detail elsewhere. One event or several, the incinerated condition of much of the bone makes it difficult to say a great deal about what happened after the buffalo jump event(s) that created Bone Bed 3. The finding of at least one intact bison calf skeleton and numerous partial articulations shows that there were so many animals heaped up that the lower ones were either not reached or only partially butchered. Given that over 50% of the bison in Bone Bed 3 were immature animals, it is likely that some were dragged out of the shelter for butchering. The absence of intact skulls suggests that the heads of most were smashed for the removal of the brains. The uneven counts of certain bones show that some parts of the animals were removed from the shelter, especially the forequarters and hindquarters, minus the feet and hooves, which were cut off and discarded on the spot. Faunal analyst Lorrain observed that the Late Archaic butchers who worked the bones in Bone Bed 3 were not as skilled or at least not as careful as the earlier Paleoindian butchers. The prime evidence is the difference in how the legs were severed from the bodies. In Bone Bed 2, the ends of the leg bones that fit into the sockets in the pelvis and scapula were intact and sometimes showed cutmarks from severing the tendons and joining tissues. In Bone Bed 3, the ball joints were often smashed. This is likely simply a reflection of the greater mass of meat—there was no need to "waste not;" the successful hunters and their families did not "wont" for meat for many moons. The relatively small number of butchering tools found amid the bones suggests that most of the butchering took place outside the confines of Bonfire Shelter, a not-surprising inference for several reasons. The only real tasks that had to be done upon the mass of dead animals would have been the initial stages of butchering wherein the animals were cut open, the favorite pieces removed (tongues, brains, and stomach contents), and the major meat parts—probably forequarters, hindquarters and backstraps—were cut loose and carried out of the shelter. In order to make use of the bonanza, the meat would have been cut into strips and hung to dry in the sun or perhaps smoked. Either way, it must have taken weeks of work to preserve and cart off the meat. Most of this work probably took place outside the shelter within the canyon, where meat strips could be spread out on numerous large, clean boulders and hung from trees, bushes, and pole frames. Along the canyon floor are also extensive flat areas of exposed bedrock as well as gravel bars that may have served as work areas for the multi-step process of hide preparation: defleshing, scraping, drying, and tanning. Where exactly these activities took place will never be known, but it wasn't in the shelter. It is also worth noting that there wasn't much evidence of any sort of activities elsewhere within Bonfire Shelter away from the main Bone-Bed 3 deposit. The only indication at all of occupation, apart from the bone bed, was two small hearths found near the back of the shelter in the thin, outer part of Bone Bed 3. It is, of course, possible that additional materials are still present at the north end of the shelter where only a few test pits were dug. The Bone Bed 2 Animals and their ButcheringWomen work outside Bonfire Shelter cutting meat

into strips for drying, a process that must have taken many days

after a successful jump kill. Drawing by Charles Shaw.

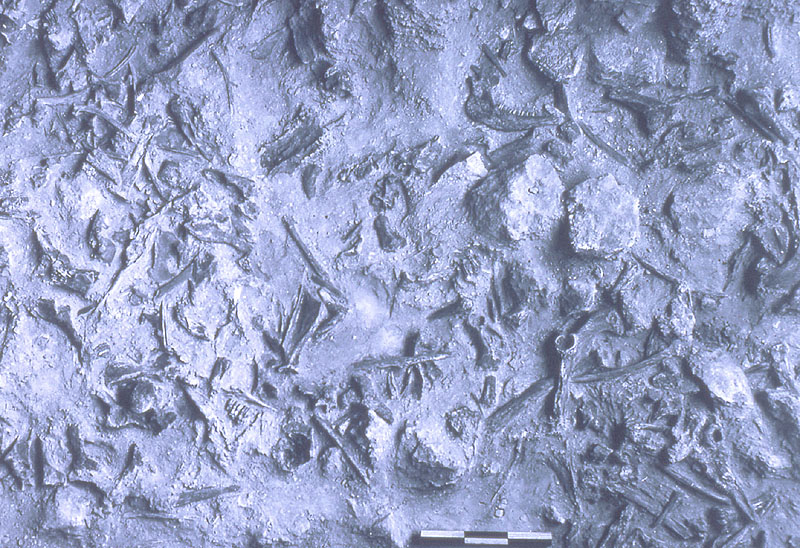

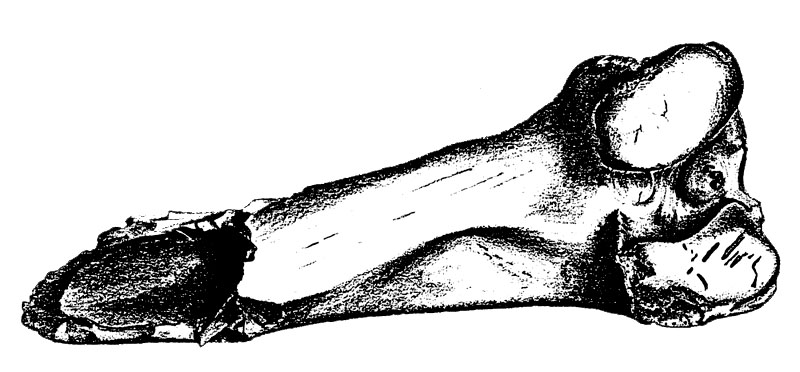

It is known that Bone Bed 2 resulted from at least three separate jumps because three distinct layers were clearly visible in certain places within the deposit. Unfortunately, many of the bones from the three or more jumps were mixed together, making it difficult to tell how many animals were killed during each event. A complicating factor is the Bone Bed 2 bonfire, which occurred after the earliest jump(s) and before the latest jump(s). Lorrain estimated that a total of 120 animals from an extinct species of bison was present in Bone Bed 2 including bulls (mature males), cows, and calves of differing ages. Bison aren't considered full adults until they reach an age of 5 to 6 years. Interestingly, over half of the animals in Bone Bed 3 were immature animals with, the 3- to 4-year-old age group having the greatest numbers. Assuming that the extinct species behaved more or less the same as modern bison, mature bulls would have been with the cows and calves only in certain times of the year, such as the fall rutting season. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the Bone Bed 3 jumps occurred in several different seasons. In contrast to Bone Bed 3 where there was abundant evidence of waste and incomplete butchering amid the dregs of one or several overwhelming successes, the evidence from Bone Bed 2 suggests a much more systematic and thorough harvest of smaller kills. Part of the reason we know a lot more about the Bone Bed 2 slaughter and its aftermath is simply because most of the evidence in Bone Bed 3 went up in smoke, so to speak, in the conflagration. The earlier Bone Bed 2 blaze was smaller and most of the bones and tools survived unscathed (or came to rest after the Paleo bone-fire). By carefully plotting and studying the distribution of different bone elements and by examining the fracture patterns and stone tool cut marks on bones, the archeologists were able to understand how much of the butchering took place within the confines of Bonfire Shelter. What they found was that following each jump the Paleoindians systematically and thoroughly butchered the animals and made use of a great deal of the animals. While little or no direct evidence survives of what they did with the hides and stomach contents, the efficiency with which the animals were dismembered and some of their bones broken apart for marrow extraction leaves little doubt that not much was wasted. From the absence of evidence for hide-scraping and cooking fires within the shelter (only one small hearth and a few scraping tools were found), we can infer that much of the post-butchering work took place elsewhere as was the case with Bone Bed 3. But most or all of the primary butchering seems to have taken place within the confines of Bonfire Shelter. The patterning of bones across Bone Bed 2 was most interesting. In contrast to Bone Bed 3, the bones in Bone Bed 2 were fully disarticulated (pulled apart), sorted into different parts of the animal, and systematically and thoroughly butchered. Despite the careful exposure of relatively large areas of the bone bed during the 1963-64 work, only seven partial articulations were recorded, situations where several of bones were found together in correct anatomical position. When articulated bones are found, it is inferred that they were still held together by flesh and connecting tissue at the time they were originally deposited. Of the seven Bone Bed 2 articulations, most of these were only two bones, indicating only a relatively small part of the animal. Compare this to the 90 articulations recorded in Bone Bed 3, where the burning hampered investigation. Many of these articulations were entire limbs or vertebral columns and in at least one case, a virtually complete skeleton. In Bone Bed 2 there was much less evidence of waste. Based on her analysis of the Bone Bed 2 bones, Lorrain outlined a fairly detailed two-step process and showed that the entire butchering process took place in the shelter. The first step was to cut apart the animal and separate the major parts that yielded different things and/or required different butchering techniques. Although short on articulations, Bone Bed 2 contained considerable evidence of the animals being divided into sections and parts and sorted into piles of like kind. For example, a concentration of partial skulls (mostly the maxilla or upper palate), mandibles, and atlas and axis vertebrae (the uppermost in the spinal column) was recorded near the rear of the shelter near the one hearth that was found in Bone Bed 2. The upper part of the skulls and horn cores were found clustered in another area of the shelter. A stack of at least seven scapulae was recorded that must have been gathered after being separated from the frontquarter. For what purpose is unknown; perhaps they were just set aside for discard. The bones of the major meat units, the frontquarters (humerus, radius, and ulna) and hindquarters (tibia and femur) show similar distributions, suggesting that the meaty legs were separated from the carcass and from the feet and then butchered in one general area of the shelter. After the prehistoric butchers completed the sorting process, the second step was to complete the butchering of each group. The skulls were cut and bashed apart at the back of the skull, presumably to extract the brains. The mandibles (lower jaws) were split apart and separated from the maxilla, probably to free the tongue. Lorrain suggested that the concentration of head parts near the hearth might indicate that brains and tongues, parts known to be favorites among historic bison hunters, were eaten on the spot. The front and rear legs were cut apart at the joints, and the meat was carefully cut from each bone. Following this the long bones were systematically broken open, no doubt to extract the fat-rich marrow. Because the long-bone fragments were not further crushed and splintered, it is obvious they were not rendered for bone grease, a common practice in later times. This was one of the few steps not taken to extract useful matter. One last pattern deserves special mention, that of stone anvils or butcher blocks. Hefty limestone boulders 1 to 2 feet (.3 to .6 meters) across were found in several places in Bone Bed 2 amid broken and splintered bones . These boulders were not present elsewhere in the natural layers immediately below and covering the bones, making it clear that they were brought in during the butchering, or perhaps a bit earlier. Such heavy stones also could have served well to dispatch wounded animals. While most of the boulders were found in the thick of things where it is more difficult to sort out which specific bones they were associated with, better-defined evidence was documented during the 1983-84 investigations at the base of Bone Bed 2. There (Stratum C), a spoke-like pattern of long bones was found arrayed around a broken limestone rock. The bones included those from at least three bison and a young horse. Several of the bones were broken, the best example being an ulna with a green (fresh bone) break and battering marks that Bement attributed to its separation from a nearby radius. This scene suggests that the Paleoindian butchers broke the leg bones atop the stones, as a modern-day butcher would use a butcher block. Who Were the Bone Bed 1 Predators?Dibble and Bement both argued that humans were the primary predators responsible for the accumulation of bones in Bone Bed 1. Lacking a smoking gun (i.e., definite proof, such as the finding of an obvious chipped-stone tool in unequivocal association with the bones), the argument is based on a series of inferences and both positive and negative evidence. First, however, consider the argument that carnivores were the main predators. Carnivores Bement carefully examined the bones to search for evidence of carnivore behavior. Carnivores such as the Late Pleistocene cats, bears, and wolves tend to leave ample evidence of their work. They kill prey animals in specific ways, sometimes puncturing or breaking the bones of their prey. In the process of devouring their prey, carnivores may break more bones, crunch up small bones, gnaw on large meaty ones, and haul entire animals or favored parts (with or without attached flesh) to feeding stations or into their lairs. Some carnivores scavenge already dead animals as well and may even chew on bones when food is scarce. Informed by studies on various carnivore behavioral

traits and telltale marks, Bement found only limited evidence for

carnivore action on the bone in Bone Bed 1 and in Bone Bed 2, where

we know humans were the main predator. In the Stratum H-1 layer

within Bone Bed 1, two horse bones had conical punctures as well

as carved grooves with U-shaped cross-sections like those made by

carnivore canines. A third bone, a mammoth long bone fragment, had

three large conical punctures, two of which were a little more than

2-inches (5.6-cm) deep. Bement narrowed the possibilities down to

the short-faced bear and the sabertoothed cat species known from

the region, scimitar cat. Both carnivores had large canines and

powerful jaws and are known to have denned in caves. The short-faced

bear was the largest and most powerful predator in North America

during the Late Pleistocene and was mainly a flesh-eater. Scimitar

cat was about as large as a modern lion and had wicked-looking,

long-curving

fangs. (For another view of scimitar cat, see http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/larson Bement used fossil specimens of scimitar cat and the short-faced bear to produce punctures in a piece of Styrofoam the same thickness as that of the mammoth bone and compared these to the size and shape of the holes. What he found was that the size and shape of the punctures in the mammoth bone most closely resembled those of the scimitar cat. Lundelius is not quite convinced because he thinks the short-faced bear had a much stronger bite and would have been much more capable of puncturing a mammoth bone. Either way, something extremely large and powerful obviously played a role in the accumulation of the bones in Stratum H-1. The only other conical puncture noted was that in a bison scapula (shoulder bone) in Stratum I (the lowest layer of Bone Bed 1). Bement suggested that this hole compared more favorably to a wolf-sized carnivore. Otherwise, there was very little definitive evidence of carnivores. Two juvenile horse long bones also in Stratum H-1 were missing one end and resembled wolf-chewed bones known from other sites. But many of the other breakage patterns often associated with carnivores were not seen in the Bonfire bone assemblage. There were, for example, numerous long bones from juvenile horses and bison that did not show carnivore damage, as might be expected if the bones accumulated in a den. Bement argued that the relative dearth of carnivore evidence weakens the carnivore-only hypothesis. The conical punctures show that one or several carnivores were present at Bonfire and did chew on horse, mammoth and bison bones, but were scimitar cats, wolves, and/or short-faced bears the primary predators or after-the-fact scavengers? Humans as Predators Multiple lines of evidence suggest that humans played a significant role in the accumulation of Bone Bed 1. Apparent cut marks were found on several different bones in Strata H-1 and I. Cuts made on fresh bone with a sharp stone tool typically create V-shaped grooves that are distinct from the more-rounded, U-shaped grooves typical of carnivore teeth. Yet both U- and V-shaped marks were found on a single horse femur (lower back leg) in Stratum H-1. Bement suggested that carnivores and humans may both have damaged the bone. In this scenario, the carnivore damage would presumably represent the scavenging of an abandoned butchering site, a pattern well known among wolves and other canines. Another clue was the presence of spiral fractures, spiral-shaped green (fresh) bone fractures that are typical of intentional breaks made by humans on fresh bone. Numerous spiral fractures were observed on Bone Bed 1 bones including the broken end of the horse femur shown in the drawing. The problem with using spiral fractures as evidence of human involvement is that they also can be created by carnivores and even by rock falls or water-borne impact. While there is no evidence of either rock falls or stream deposits at Bonfire in Bone Bed 1, there is at least some evidence of large carnivores. Perhaps more convincing is the finding of several apparent bone tools. The same horse femur with a spiral fracture and both U- and V-shaped incisions also has what Bement describes as smoothing and polish along the broken edge. He thinks this may well be a butchering tool. Another example is a broken bison ulna (lower front leg) bone that forms a smooth point bearing numerous V-shaped cut marks; Bement interprets this bone as a butchering tool. The finding of numerous apparent cut marks begs the question: where are the stone tools that presumably left the cuts. Perhaps these were removed from the scene or else dropped in a different part of the shelter. Yet another suggestive finding in Stratum H-1 is that of several large mammoth bones with small depressions caused by the impact of something hard and/or sharp. Both a pelvis (hip) fragment and a cervical vertebra (spinal bone from neck) had apparent dents that Bement believes resulted from these large bones being used as anvils during butchering. The opposite face of the vertebra also had numerous small triangular depressions seemingly caused "by pressing a sharp edge into a soft material." These could have been caused by small angular limestone spalls upon which the bone was lying if a strong force was applied to the opposite face. Finally, there is the repeated pattern of the occurrence of large limestone blocks amid the bones in direct association with splintered and broken long bones. This pattern has been documented in the three major Bone Bed 1 layers as well as in Bone Bed 2 and Bone Bed 3. Bement argues that these are butcher blocks or anvils where long bones were broken to extract marrow and upon which other bones were laid during the butchering. See Bone Bed 1 for details. In summary, while much of this evidence is circumstantial and subject to alternative explanation, collectively the various patterns just described led Bement to tentatively accept the idea that humans were the major predator responsible for the accumulation of the bone layers in Bone Bed 1. To explain how the animals were killed, Bement offered the following Natural Trap hypothesis: It is proposed here that the E, H-1 and I bone beds resulted from the use of Bonfire Shelter as a natural trap by man. Mile Canyon is a box canyon with limited lateral access and a deep waterhole at its head.... Animals were drawn into this canyon by the waterhole and probably the vegetation it supported. Bonfire Shelter, 1/4 mile downstream from the waterhole, provided a natural trap. Its downstream end would have allowed easy access from the canyon floor while its upper end was sealed by roof collapse. Large roof blocks likewise obstruct the front of the shelter without blocking sunlight. Small groups of animals moving up the canyon toward the waterhole could have been diverted into the shelter where hunters, positioned on the huge roof blocks, could easily kill the animals. Perhaps the limestone blocks associated with the skeletal remains entered the cave as implements of the kill and were later used in the proposed butcher block-bone smashing capacity as a matter of convenience. Following the kill, the animals were butchered within the shelter. Some processing of the meat (such as cooking and drying) may have occurred within the shelter, although a locus for this activity has not yet been found. Abandonment of the shelter upon completion of the butchering process allowed scavengers to enter and further disarticulate, distribute and digest the bone material. So, after reading all this and seeing some of the evidence, who do you think was the main predator responsible for the Bone Bed 1 accumulations, (hu)man or beast? As far as most archeologists are concerned, the question is still open unless and until a smoking gun can be found. |