The Archeology—Bone Bed I

|

The deepest and oldest layers in Bonfire Shelter containing animal bones are known collectively as Bone Bed 1 and are present only in the central part of the shelter. Together the Bone Bed 1 layers are 20-24 inches (50-60 cm) thick and begin directly below Bone Bed 2 at a depth of 6.5 ft (2.2 m) below the shelter's modern surface). There is only a single radiocarbon date from Bone Bed 1, and it establishes a minimum age of 11,500 B.C. Most likely Bone Bed 1 is several thousand years older. Several facts about Bone Bed 1 are remarkable.

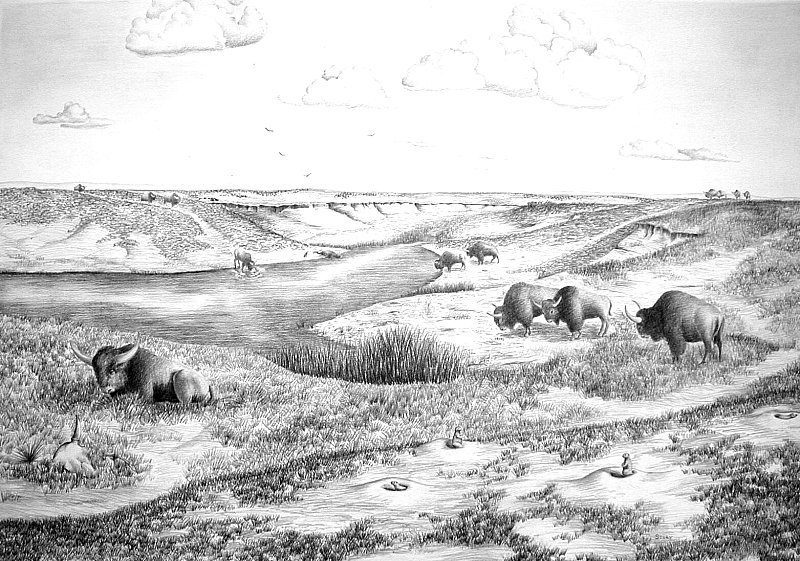

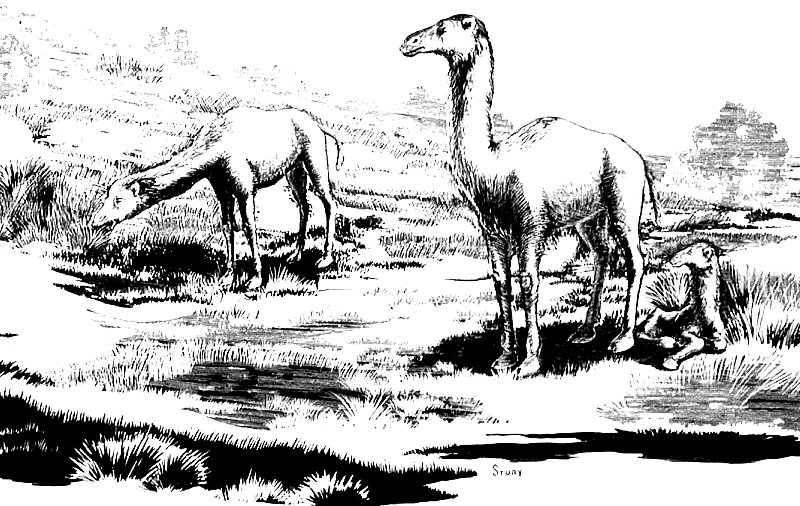

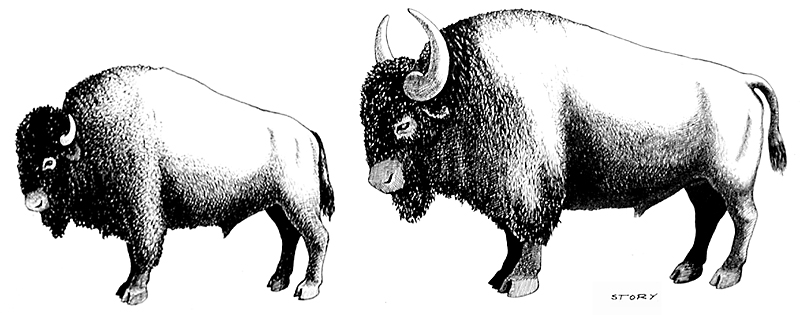

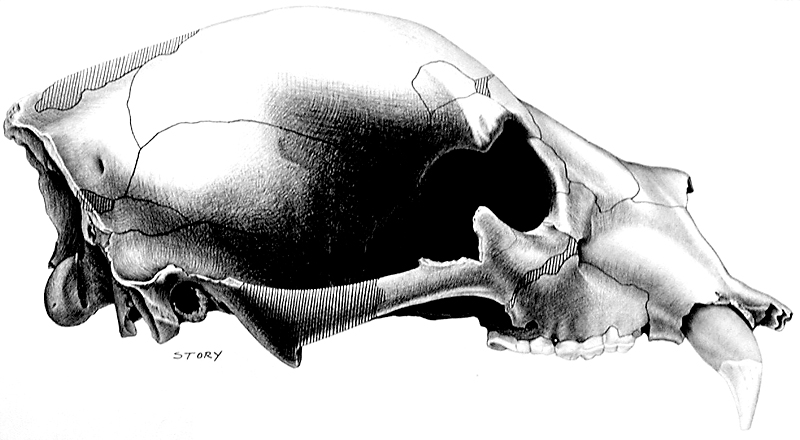

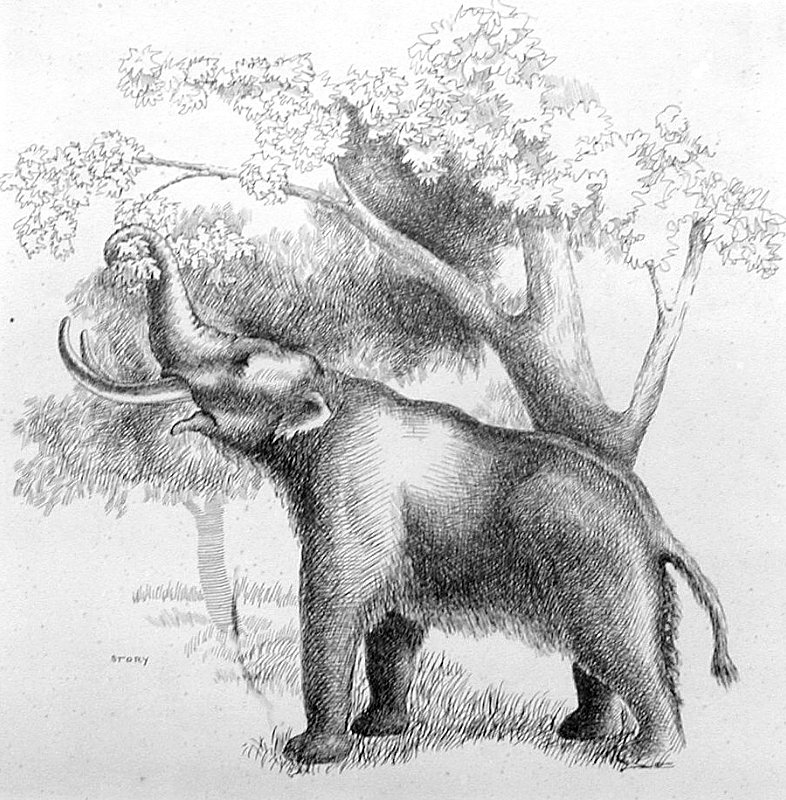

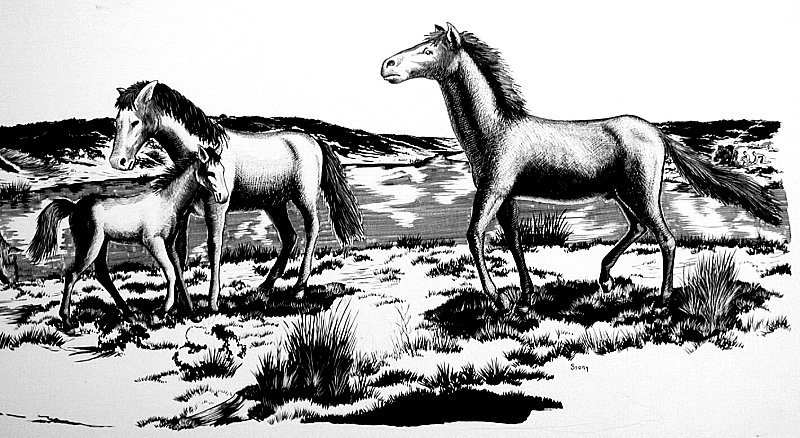

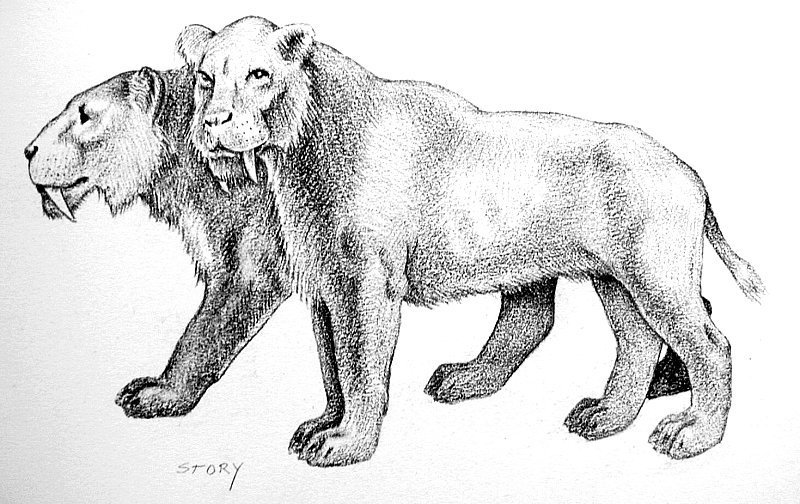

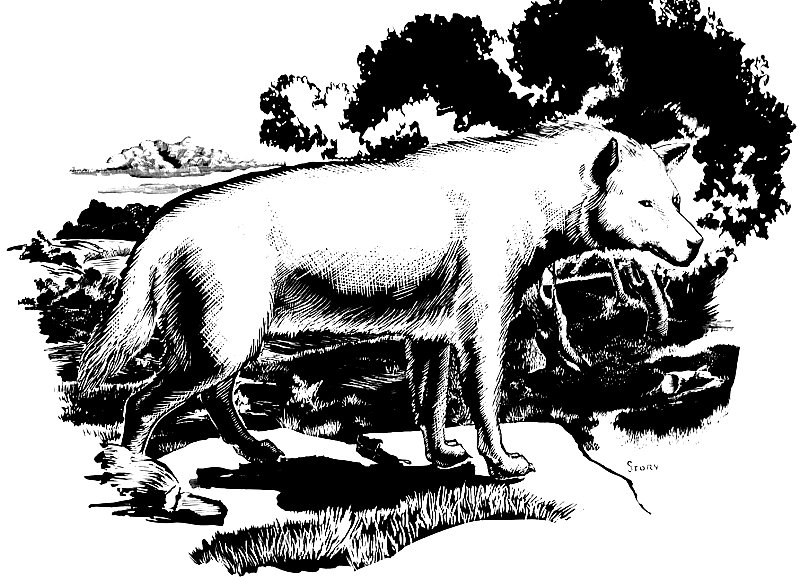

These include wooly (Mammuthus sp.), camel (Camelops hesternus), at least one species of horse (Equus francisci), a small antelope (Capromeryx sp.), and bison (Bison antiquus or occidentalis). All of these animals disappeared from Earth at the end of the last Ice Age (the Pleistocene) before 9,000 B.C. Although it is unlikely that humans alone were responsible for the Late Pleistocene extinctions in North America, they almost certainly contributed to the wave of extinctions brought on by major climatic changes. Drawings of many of the Ice-Age animals whose bones were found in Bone Bed 1 at Bonfire help us visualize the environment that early human groups in the region would have encountered. The bison, Ice-Age and modern, that were killed at Bonfire probably spent most of their lives on the southern Plains to the north. Only one bone found in the uppermost layer of Bone Bed 1 is of a species that survives today, the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). The species list given here does not include any of the small animals (rats and such) present in the sediment samples collected as microfauna samples; these have yet to be fully analyzed.

Of the five bone-bearing layers now known (Strata D, E, H-1, H-2, and I), several are very thin and do not extend across the entire excavated area in the center of the shelter. It is likely that if the excavation area is ever expanded in the future, other minor layers will be found within Bonfire's lower deposits. Stratum D contains only the gray fox bone and Stratum H-2, only three antelope bones. The other three layers have multiple species and are considered by Bement to represent separate bone beds. These are discussed below.

By the time Bone Bed 1 began forming, perhaps between 12,000-14,000 B.C., the floor of Bonfire Shelter was already high and dry above the down-cutting canyon floor (although probably not by much). Lacking any evidence of stream deposits that might have washed bones into the shelter, there is no other credible alternative to explain the presence of splintered and broken bones from a variety of animals, many quite large. Predators carried or dragged dead animals or body parts into the shelter or else they trapped animals in the cave and killed them there. But which predators? The most likely candidates include humans and three now-extinct carnivores: the short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), a sabertoothed cat known as scimitar cat (Homotherium serum), and wolf, possibly the dire wolf (Canus dirus) or gray wolf (Canus lupins). Although lacking definite proof such as the presence of stone tools or hearths, the Bonfire investigators have argued that humans were the chief Bone Bed 1 predator. See Who were the Bone Bed 1 Predators? for a summary of the arguments and evidence.

The jump explanation can be rejected for two reasons.

One is that Bone Bed 1 is concentrated in the central, interior

part of Bonfire Shelter and is not present at the south end adjacent

to the talus cone where both of the upper bone beds are concentrated.

Secondly, there are multiple species present in Bone Bed 1 including

species that are poor candidates for having been driven over cliffs.

Mammoths were extremely large creatures that, based on what is known

about their modern elephant cousins, were highly intelligent and

wary. They lived in smaller social groups (families) and were not

as prone to bolt and run pell-mell as bison. Camels, horses, and

antelope are all fleet-footed animals that should have been able

to evade small groups of hunters upon the rolling grassy plains

that probably covered the uplands above Bonfire Shelter in the Late

Pleistocene. There is no definitive evidence that any of these species

were killed by the jump method anywhere in North America. See Who

were the Bone Bed 1 Predators? for an alternative explanation. The Bone Bed 1 LayersThree of the layers in Bone Bed 1 (Stratum E, H-1, and I) could and probably should be considered as separate bone accumulations (i.e., bone beds) on their own merits. All three probably formed in a relatively short time and contained numerous large bones of at least two different creatures. All three also had what Bement believes is a highly significant pattern: the presence of limestone blocks lying in association with splintered and broken long bones. Stratum E Bone BedStratum E contained the remains of at least three horses (mostly juveniles), a camel, a bison, and a mammoth. Bones from all four species were found close together and in apparent association with one large limestone block (somewhat larger than a basketball) and several smaller ones. Most of these bones were hind- and front-leg bones of horse, bison, and camel. Not far away were several other clusters of smaller limestone blocks and splintered bone. Stratum H-1 Bone BedStratum H-1 contained bones from at least two horses and a young mammoth. The horse bones were by far the most numerous. One horse was a mature adult (at least 3.5 years old) and one was a colt, less than a year old, based on dental eruption patterns and fusing of certain bones. The range of bone elements present, leg and feet bones, skull and teeth fragments, and various vertebrae, suggest that the entire carcass was once in the shelter. The mammoth was less well represented, but the presence of mandible fragments, a vertebra, and fragments of the pelvis, tibia (upper front leg), and a rib, suggests that much of the animal was in the shelter. Once again there were several clusters of limestone blocks and broken bones. The most impressive was a line of five limestone rocks, two of which were directly associated with fragmented horse bones including the ends of two ulnas (lower front legs) and one sacrum (tail bone) broken along its center line. Stratum I Bone BedThis layer contained bones from a large bison and the teeth from at least one adult horse. The bison was represented by a variety of post-cranial (everything below the head) elements including vertebra, leg bones, foot bones, ribs, shoulder, and pelvis. Three large boulders dominated the bone bed, but these rested on lower layers and thus pre-date Stratum I. Seven smaller but still hefty limestone blocks were found amid fractured bison bones. In another area of the deposit, a separate limestone block was found alongside more fragmented bison bones and several horse teeth. |