Floyd V. Studer was an explorer, promoter,

civic leader, watchdog, and kingpin, a determined man whose

impact on the study of Plains Village sites in the Texas Panhandle

is hard to exaggerate. This publicity photo was probably taken

around 1940. Panhandle-Plains Historical Society (PPHS) archives. |

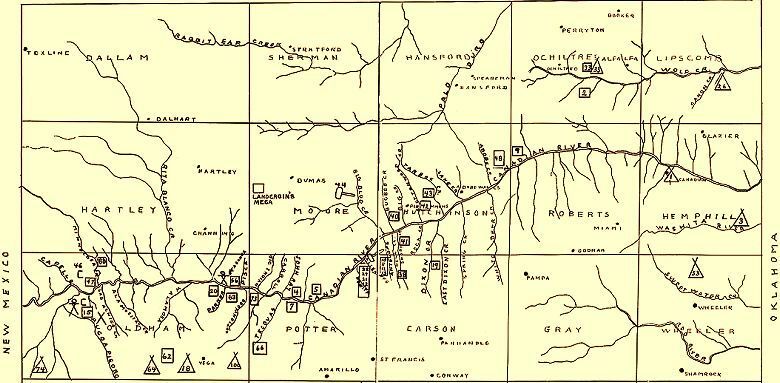

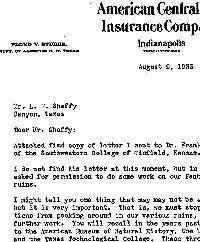

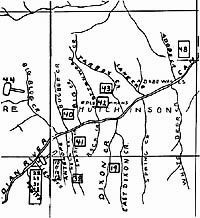

Detail of Hutchinson County area of Studer’s

1931 map of the northern Panhandle that was published by Moorehead.

The map was intentionally incomplete and deliberately misleading

in places—Studer feared that unwanted visitors would

destroy the sites. Click to see larger images and

more of map.

|

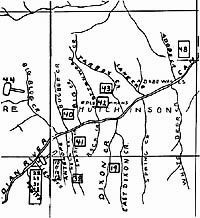

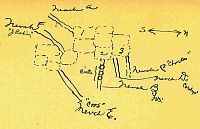

Diagram by Floyd Studer of ongoing work

at Alibates 28 in July, 1932. The apparent excavators are

identified beside each trench, including “FVS”

(Floyd V. Studer), “Carolyn” (Studer), “Charles”

(Renfroe), and “J. Robin” (Allen). During this

period, Studer was assisted by various friends and members

of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society. Map from the PPHS

archives; identifications by Chris Lintz. |

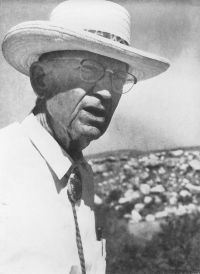

Floyd Studer at the Alibates quarries in

1935. The photo was taken by A. T. Jackson of the University

of Texas during a brief visit to the area. TARL archives.

|

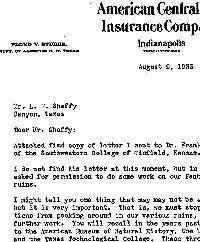

This 1933 letter from Studer to L. F. Sheffy,

the chair of the history department at West Texas State Teachers

College in Canyon, calls attention to the danger of allowing

outside institutions to dig at the Panhandle's Plains Villages.

"We must stop these visiting institutions from

pecking around in our various ruins, and ruining them for

further work." Studer was a prolific correspondent

and this is one of many letters he wrote as a self-styled

advocate and defender of the region's archeological resources.

PPHS archives. Click to see enlarged image of entire

letter. |

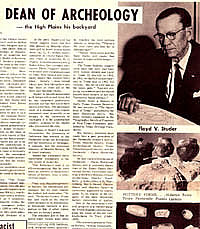

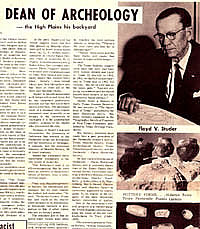

Article on "businessman-historian"

Floyd V. Studer that appeared in the February 5, 1963 edition

of The Amarillo Citzen. PPHS archives. |

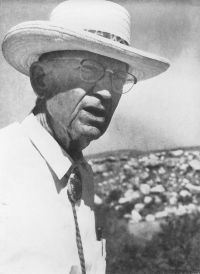

Floyd V. Studer at the 1965 dedication

of the Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument. This photo

appeared in the Amarillo Globe-News. PPHS archives. |

During the prolonged drought of the early

1930, dust storms like this recent example near Turkey, Texas,

turned much of the Southern Plains into a “dust bowl”

and sent many farming families to ruin. Photo by David L.

Arnold, Ball State University. |

Inspection visit during WPA excavations

at Antelope Creek 22 in 1938 or 1939. C. Stuart Johnston is

on the far right with his young wife Margaret. Floyd Studer

is in the center background facing the camera. |

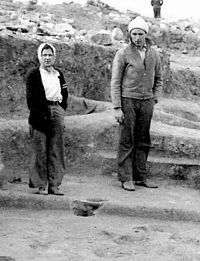

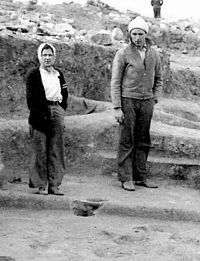

Ele and Jewel Baker at Antelope Creek 22,

probably in the late fall or winter of 1939. PPHS archives. |

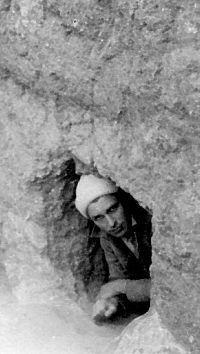

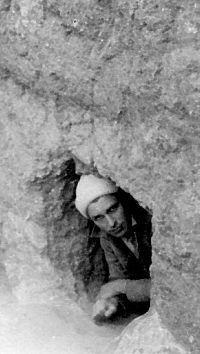

Ele Baker in passageway to Room 2 at Antelope

Creek 22. Studer was much taken by the narrow passageways,

which he thought mainly provided ventilation. He insisted

that the Antelope Creek rooms lacked doorways and that access

must have been through roof entries. PPHS archives |

Jewel Baker restoring large Borger Cordmarked

jar at the WPA laboratory at the Panhandle-Plains Museum.

Photo taken in January 1939 by H.C. Pipkin, an Amarillo lawyer

who was one of Studer’s close friends and supporters.

Other photos show Pipkin with expensive photographic equipment,

suggesting that it may have been he who took many of the publicity

photos of the WPA work. PPHS archives. |

Dedication statement by Ele and Jewel Baker

prepared for the 1968 four-copy edition of their original

WPA reports. |

|

By the late 1920s Floyd V. Studer

controlled access to most of the known Plains Village sites in the

Texas Panhandle. How and why he did this is a part of the fascinating,

but little-known story of a larger-than-life man. Studer was an

explorer, promoter, civic leader, watchdog, and kingpin, a determined

man whose impact on the study of Plains Village sites in the Texas

Panhandle is hard to exaggerate. For over 50 years, from the first

excavation at Buried City through the early 1960s, Floyd Studer

had a strong hand in virtually all archeology done in the Texas

Panhandle.

Studer was bitten badly by the archeology bug as a

15-year-old student during the 1907 expedition to Buried City. Perhaps

it was really more of an exploration bug combined with natural curiosity

and the pride of a native son of the Panhandle. Regardless, from

that day onward Studer sought out any and all archeological sites

in the Texas Panhandle, especially the Plains Villager sites with

masonry ruins. He was also fascinated with the fossil bones of ancient

animals; in the early 20th century, archeology and paleontology

were seen as closely related studies—both involved exploration

and digging. Studer had no formal training in archeology, but as

he put it in 1955:

I have made of it a lifetime relief occupation. … For 45

years, whenever possible, I worked on those ruins—surveying,

mapping, photographing, digging. … While engaged in commercial

activities in Amarillo, this was my relaxation on weekends and

holidays. Every means of transportation made available in those

years was used—shanks’ mare, horseback, buckboard,

motorcycle, Model T, later models—until finally the airplane

solved a lot of the problems.

As Studer explored the Panhandle, he developed an

extensive network of local contacts through personal, family, banking,

and insurance connections. In the 1920s he obtained “scientific

leases” from ranchers within the Canadian Valley that he believed

gave him the right to decide who could investigate the sites. In

part he was motivated by his sense of ownership—it was he

who found and recorded most of these sites and he regarded the Canadian

Breaks as his "turf." Studer also clearly felt a strong

sense of stewardship—like Moorehead, Studer recognized that

many of the sites were threatened by casual artifact seekers, museum

collectors, and development.

Studer played an instrumental role in the Panhandle-Plains

Historical Society and the establishment and development

of the Society’s Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

in Canyon, the first state museum in Texas. In 1931, two

years before the museum first opened to the public, Studer signed

over his scientific leases to the society and its fledgling museum

in exchange for a non-salaried appointment as the museum’s

Director of Archaeology and Paleontology. This volunteer post gave

him a headquarters and solidified his control of Panhandle archeology

and paleontology for the next two decades. The museum was closely

connected to West Texas State Teachers College (West Texas A&M

University today) and it was Studer’s influence that led the

college to create a teaching position in paleontology and anthropology

in 1934.

EXCLUSIVE PRIVILEGE to

INVESTIGATE this LOCATION

and other Archaeological and Paleontological

Sites on this ranch

HAS BEEN LEGALLY GRANTED

Trespassers will be prosecuted under the law

Panhandle Plains Historical Society

—sign posted by Floyd Studer

In 1955, Studer stated that he had “located,

mapped, and fully recorded over 200 Indian sites,” a claim

that must be tempered by the realization that most of Studer’s

written records were cursory even by the standards of the day. He

did keep a master numbered list of 212 sites that would become the

basis for the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum’s site records

and that live on today in site names such as Alibates (Ruin)

28 and Antelope Creek (Ruin) 22.

Studer was famously secretive and kept much of what

he knew to himself. His regional map that Warren King Moorehead

published in 1931 was intentionally incomplete, an omission attributed

in the report to the need to protect the sites and the landowners

from unwanted visitors. Not noted is the fact that Studer deliberately

mislocated some of the sites. He promised that one day he would

publish a complete map and report on his survey work, but never

did so.

Studer's secrecy and desire to obtain scientific

leases seem to have been spurred by concern that professional archeologists

from outside the region would plunder the sites for their own museums

and institutions. This concern was well-founded. A.V. Kidder, the

leading American archeologist of the day, decried the unscrupulous

collection practices of some museums in his 1932 study, Artifacts

of Pecos Pueblo.

Studer's suspicious attitude about outside archeologists

was encouraged by Moorehead, perhaps because he himself felt slighted

by (and in competition with) university-affiliated researchers.

Studer always gave Moorehead credit as being his most important

influence and chief advisor. Nonetheless, Studer did correspond

with and cooperate with other archeologists, such as Alden Mason,

Ted Sayles, and Curry Holden. He allowed these men to dig at certain

of the largest village sites.

During the early to mid 1930s, Studer carried out

limited excavations at numerous sites, including Antelope

Creek 22, Alibates 28, and Coetas

Creek 55. He was assisted by various friends and members

of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society. Most of this work appears

to have been done sporadically on weekends and holidays. The excavation

and documentation methods were typical of the era, which is to say

they were rather haphazard by today's standards. Essentially, Studer

dug into and cleared obvious rooms, focusing on the major architectural

elements such as doorways, fireplaces, and walls. Rich middens (trash

heaps) and burials were the only features outside the ruined walls

that were noted. Only select artifacts were collected and most animal

bones and charred plant remains were routinely discarded. Studer

published several summary articles on his work in the 1930s, with

mention of select architectural details of certain rooms at certain

sites, but none of his excavations were ever fully reported.

In the 1930s Studer also became a major civic leader

in Amarillo and held posts in many community organizations. Archeology

and the promotion of all things Panhandle remained his passion throughout

his life. He did not relinquish his position at the museum until

Jack Hughes was hired in 1952 to take over as curator

of archeology and paleontology. Studer remained an active member

of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society, served on its board

and held its highest elected offices in the mid to late 1950s. Toward

the end of his life he and Amarillo businessman Henry Hertner

initiated the local efforts that led to the creation of the Alibates

Flint Quarries National Monument in 1965. After Floyd Studer

died in 1966, his widow turned over his remaining archeological

records to Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum and the National Park

Service, the federal agency that administers Alibates.

One notable, but understandable, aspect of Studer’s

mindset was his insistence on viewing and interpreting the archeology

of the Plains villagers of the Texas Panhandle through a Southwestern

lens. He considered the Panhandle part of the American Southwest

and emphasized this in many ways. Although he would later claim

that it was Moorehead who coined the term “Texas Panhandle

Pueblo Culture,” it first appears in Studer’s

section of Moorehead’s 1931 report, and it was Studer who

continued to use the term for decades. In a separate 1931 article,

Studer described local ruins as “Post Basket Maker sites,”

again implying a close relationship to the Southwest.

In the 1930s, the American Southwest was, as it still

remains today, the best-known archeological region in the country.

The abundant masonry ruins, the excellent preservation conditions,

and the fact that numerous native peoples still lived there made

the Southwest a scientific Mecca. Because of the intense archeological

attention and the fact that many ruins had preserved timbers that

could be dated through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), the

Southwest was also the only region that had a solid prehistoric

chronological framework. The tree-ring dates and the pottery sequence

developed by famed archeologist A.V. Kidder at

Pecos Pueblo resulted in the Pecos Classification of 1927. This

scheme was worked out by Kidder and the participants of the first

Pecos Conference, an annual meeting of the top

Southwestern archeologists. The proposed cultural stages/periods

known as Basketmaker I through III,

followed by Pueblo I through V,

became widely used throughout the Southwest and beyond.

In the 1930s Studer attended several Pecos Conferences

and was influenced by what he learned, finding much more of interest

in the Southwest than he did in other areas of Texas. Studer had

dutifully written the reigning archeological authorities in Texas,

Abilene physician Cyrus Ray (lead founder of the

Texas Archeological Society) and professor J. E. Pearce

at the University of Texas, asking their advice on the architecture

he was exploring in the Panhandle. But neither offered Studer much

help because they were unfamiliar with the region and they did not

know of similar ruins elsewhere in Texas. Studer had better luck

when he wrote archeologist Frank C. Hibben at the

University of New Mexico. Hibben’s willingness to give Studer

guidance was probably one of the main reasons Studer adopted Southwestern

terminology. (Later, it was Hibben who suggested to Studer that

he hire a promising student, Ele Baker, to direct

WPA digs in the late 1930s.)

Studer's strong belief in a Southwestern orientation

influenced Panhandle archeology in profound ways for many years,

but other researchers saw increasing indications to the contrary.

In his later years, Studer seems to have struggled to reconcile

his long-standing Southwestern bias with the mounting evidence that

his beloved Panhandle ruins were built by Plains Indians. Near the

end of a short 1955 review article, his last publication on the

subject, he wrote:

The Texas Panhandle Pueblo Culture apparently

originated from the pottery-making people who appeared on the Central

Plains after 900 A.D., reaching the valley of the Canadian some

two or three centuries later.

Yet, in the same article Studer attributed the origins

of the “first American apartment houses” (i.e., Antelope

Creek ruins) to the Southwest, an idea he never let go of.

Beginning in the early 1930s, Studer speculatively

identified what he felt were close architectural parallels between

the houses he and others excavated at Antelope Creek 22 and other

Panhandle sites with Southwestern Pueblos. Among these were what

he called ventilator shafts, stone deflectors, sipapus (symbolic

spirit holes), and kivas (underground ritual or assembly rooms).

Although there is little doubt that Antelope Creek villagers did

incorporate some broad architectural ideas from Southwestern peoples,

Studer consistently downplayed or ignored the equally compelling

architectural similarities with Plains Village sites up and down

the Plains. Studer’s Southwestern bias can still be seen today

in the scale model reconstruction of the Antelope Creek 22 ruin

that is on display at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. Under

his direction, WPA workers reconstructed the site as a Southwestern

Pueblo complete with flat roofs, roof entries, and attached kivas.

Today few experts accept this reconstruction, because there is little

convincing evidence for the existence of kivas, sipapus, or flat

roofs with roof entries in Antelope Creek architecture.

Even so, Floyd Studer’s legacy lives on in the

Texas Panhandle in countless ways. He literally and figuratively

put the region on the nation’s archeological map. Throughout

his life he worked to protect the ruins left by the “Texas

Panhandle Pueblo Culture” and to call public and scholarly

attention to their importance. It was he who had the vision to tap

into the New Deal funding to develop archeological and paleontological

programs at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, and he was largely

responsible for uniting the museum with the West Texas State Teachers

College. From this union he was able to hire C. S. Johnston and

Ele and Jewel Baker, and these people worked miracles in securing

funding for programs and rigorously documenting large-scale WPA

excavations.

New Deal Archeology

The 1930s was tough time in the Texas and Oklahoma

Panhandles. The entire country was mired in the Great Depression

that followed the 1929 stock market collapse. Simultaneously, a

prolonged drought (1931-1934) turned much of the Southern Plains

into a “dust bowl” and sent many farming

families to ruin (and to California). In response to the country’s

woes, the Federal government under Franklin D. Roosevelt created

an unprecedented series of relief programs known collectively as

the New Deal. Because the main goal was to put

people back to work, labor-intensive archeological and paleontological

projects were seen as effective ways to do just that. To land such

a project, a state or local institution, usually a university, had

to sponsor and administer the work. Through this process, the New

Deal resulted in massive archeological excavations in the Southern

Plains and many other areas of the country in the late 1930s and

early 1940s.

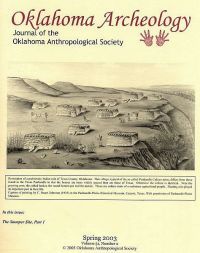

A four-part series of articles recently published

in Oklahoma Archeology (the journal of the Oklahoma Anthropological

Society) tells the intriguing story of the New Deal work projects

carried out at the Stamper site, a large Plains

village along the Beaver River in Texas County in the Oklahoma Panhandle.

Trial excavations sponsored by the University of Oklahoma in 1933

led to funding from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

(FERA) for major excavations carried out in 1934-1935 under the

direction of C. Stuart Johnston and then Fred

Carder. Their work showed the slab-house construction typical

of Antelope Creek sites was also present in the Oklahoma Panhandle.

FERA also supported Oklahoma Historical Society excavations at the

Roy Smith site, another slab-house ruin, near Turpin,

Oklahoma.

In the fall of 1934, Johnston was hired away from Oklahoma

by the West Texas State Teachers College (WTSTC) in Canyon, Texas,

to teach geology and anthropology courses. Floyd Studer was almost

certainly responsible for Johnston's hire. Young, handsome, and brilliant,

C. Stuart Johnston soon became a popular teacher and an effective

administrator of WPA grants. He and his wife, Margaret Johnston,

11 years his junior, were the talk of the town. Using his Oklahoma

experience with FERA, Johnston successfully won federal funding for

a series of major paleontological surveys, digs, and fossil restoration

projects as well as archeological projects in the Texas Panhandle.

After mid-1935, the funding came from the Work Progress

(or Projects) Administration (WPA) for projects sponsored

by the college and the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society and headquartered

at the museum.

Stuart Johnston oversaw many WPA paleontological projects

over the next few years as well as several archeological projects.

Meanwhile he continued to teach and was under increasing pressure

to finish his dual Ph.D. in paleontology and anthropology at the

University of Oklahoma. Johnston had completed a paleontological

dissertation and for his anthropology degree he only needed to write

a publishable paper. To satisfy this requirement, he wrote a preliminary

report on the WPA work at Antelope Creek 22, but ran afoul of Floyd

Studer, whose permission he had failed to obtain. While Johnston

was the official scientific administrator of the WPA work, Floyd

Studer was the sponsor’s (WTSTC) representative in charge

of the archeological investigations and he was determined to maintain

his proprietary interests in the region.

Cracking under the pressure, Johnston fled to Boston

in the summer of 1939. Not long thereafter, he was found dead in

a Boston boarding house. Ironically, Studer had apparently relented.

Shortly after Johnston’s untimely demise, his article on Antelope

Creek 22 appeared in the 1939 Bulletin of the Texas Archeological

and Paleontological Society.

Despite Johnston's death, the WPA continued to fund

archeological investigations of eight of Studer’s Antelope

Creek sites. Under Studer’s supervision, the fieldwork was

directed by the husband and wife team of Ele and

Jewel Baker. Ele was the son of “Uncle

Billy Baker,” a Soil Conservation Service agent in

Cimarron County, Oklahoma, and avid amateur archeologist. Ele had

directed the 1934 FERA excavations at the Kenton Caves in

the Oklahoma panhandle before going to the University of New Mexico

to begin his undergraduate degree in archeology. While in New Mexico,

he participated in field schools run by Frank Hibben at Chaco Canyon

and Paako. Running low on money, Ele and Jewel ran Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) projects in northern New Mexico,

excavating and restoring two Spanish missions, Quarai and Jemez.

Arriving in Texas in 1938, the Bakers proved to be

a capable and hard-working pair. Ele’s official title was

Project Superintendent, while Jewel served as Assistant Archaeologist

in charge of artifact handling and cataloguing (she also seems to

have excavated most of the burials). The field crew consisted of

20 laborers from the relief rolls of Potter County plus two professional

workers; three additional workers labored in the laboratory at the

museum. Early each morning the Bakers each drove a project truck

around Amarillo picking up WPA workers at their homes and then out

to the sites under excavation, returning late in the day. They also

scavenged building materials on these morning drives to construct

the field laboratory at Alibates Ruin 28 modeled after the Antelope

Creek houses they were digging. From 1938 to 1941, the WPA teams

carried out extensive excavations along Antelope Creek (Ruins 22,

22A, 23, 24), Alibates Creek (Ruins 28, 28A, 30), and Corral Creek

(Chimney Rock Ruin 51).

Because of the Bakers' experience, their sizable workforce,

and procedures introduced by the WPA, the work was far more systematic

and better documented than previous archeological excavations in

the region. As they excavated and documented house after house at

site after site, the Bakers were able to see both consistent patterns

in architecture among Antelope Creek villages as well as lots of

variation.

Following up on suggestions made by famed Plains

archeologist Waldo Wedel, the Bakers noted similarities

between the Canadian River sites and sites along the Republican

River in Nebraska. With the exception of building techniques and

the use of local resources, the material culture of the Antelope

Creek sites closely resembled that of Plains Village sites in the

Central Plains. The Bakers noted that the Stamper site (“a

single site of the same culture found near Guymon, Oklahoma”),

100 miles to the north, was the only other known locality where

Antelope Creek style architecture occurred. (Actually, several other

Oklahoma Panhandle sites, such as the Roy Smith site, were also

known to have similar architecture.)

With World War II looming, WPA funding ended abruptly

in 1941. The Bakers were able to prepare the required quarterly

reports and complete two final WPA project reports on their work,

but these would remain unpublished for almost 60 years. The reports

contain careful descriptions of each room with sketch maps and tabulations

of artifact counts, but little real synthesis and interpretation.

Like so many WPA-funded archeological projects, the notes and collections

languished for decades in a half-finished state. Things became separated,

photographs and maps were neglected, and no one stepped in to take

on the onerous task of finishing the work and synthesizing the findings.

In the early 1940s, Studer wrote a formal report on

the Alibates sites (much of it taken from the Bakers' WPA reports)

and apparently hired ghost writers to write a report on the Antelope

Creek sites (also heavily dependent on the Bakers’ work),

intending to publish these under his own name. Unfortunately, neither

report was published. Through the succeeding years, sections from

the WPA reports were disassembled—some portions of them ended

up in the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum and some went to the

National Park Service. In the 1980s, the WPA documents were reunited

by Chris Lintz during his dissertation research. Another positive

development is that the federal government through the National

Park Service has provided funding in recent decades to consolidate

and upgrade the WPA records and collections at the Panhandle-Plains

Historical Museum.

|

Close up of Studer’s logo, the traced

outline of an upside down Washita arrow point with a capital

“S” inside. Washita points are common at Antelope

Creek sites. PPHS archives. |

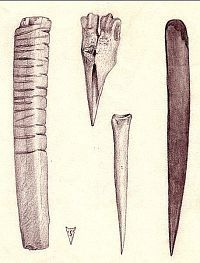

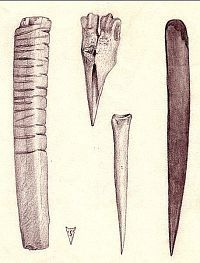

Drawing by Floyd Studer of Antelope Creek

bone tools. Studer was an artist as well as a photographer.

PPHS archives. |

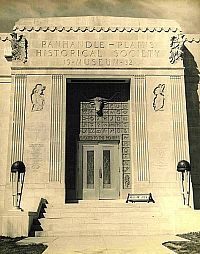

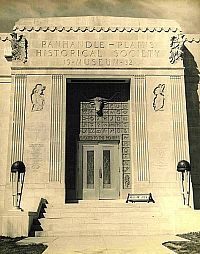

The Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum,

Texas’ first state historical museum, opened to the

public in 1933. It was created by the Panhandle-Plains Historical

Society in partnership with West Texas State Teachers College

(now West Texas A&M University). PPHS archives. |

Scale model of an Antelope Creek house

as envisioned by Floyd Studer. The flat roof and roof entry

ideas are conjectural details that Studer borrowed from Southwestern

pueblos. This model was made during the WPA era and can still

be seen at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. Photo by

Steve Black. |

This photograph commemorates Warren King

Moorehead’s visit to the Panhandle-Plains Historical

Museum in 1938 or 1939. The men stand behind the detailed

interpretive model of Antelope Creek 22 built by WPA workers

under the direction of Floyd Studer. Studer is the man on

the far right and stands next to Moorehead. PPHS archives.

|

Detailed interpretive model of Antelope

Creek 22 built by WPA workers in the late 1930s under the

direction of Floyd Studer for permanent display at the Panhandle-Plains

Historical Museum. Studer based the model on the standing

pueblos of the nearby American Southwest; the flat roof, roof-top

ladder entries, and attached kiva (circular room at right)

were largely products of his imagination. PPHS archives. |

WPA excavations in progress at Alibates

Ruin 28, year unknown. PPHS archives. |

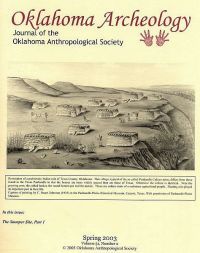

The first article in a fascinating four-part

series on the Stamper site appeared in the Spring 2003 edition

of Oklahoma Archeology. In this series, author Christopher

Lintz tells the intriguing story of the 1934-1935 excavations

at a large Plains village located near the North Canadian

River in Texas County, Oklahoma that is relevant to the ruins in Texas. |

Margaret Johnston, stylishly attired in

a leather aviator’s hat and lace-up knee boots, visiting

Antelope Creek 22 during the WPA excavations in 1938 or 1939.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. |

WPA field laboratory at Alibates 28. This

structure was built by the WPA crew to resemble the Antelope

Creek houses they were uncovering. The Southwestern-style

flat roof conformed to Studer’s ideas. PPHS archives. |

U.S. Congressman Marvin Jones during a

visit to Alibates Ruin 28, possibly in 1939. Studer brought

many influential citizens out to see the WPA work. Jones was

a powerful legislator and may have helped Studer and the WTSTC

gain continued WPA funding. PPHS archives. |

Printed sign Studer posted on the WPA

sites under investigation. “EXCLUSIVE PRIVILEGE to INVESTIGATE

this LOCATION and other Archaeological and Paleontological

Sites on this ranch HAS BEEN LEGALLY GRANTED. Trespassers

will be prosecuted under the law. Panhandle Plains Historical

Society.” PPHS archives. |

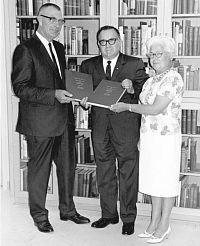

Ele and Jewel Baker present PPHM director

C. Boone McLure (on left) with bound copies of their WPA final

reports in special ceremony in 1968. The two volumes were

compiled and issued by the Alibates National Monument Committee

(Henry Hertner, chairman), but only four copies were printed.

Most would-be readers would have to wait until 2000, when

the Panhandle Archeological Society united the two volumes

under one cover and republished the Baker’s report.

PPHS archives. |

|