Squawteat Peak

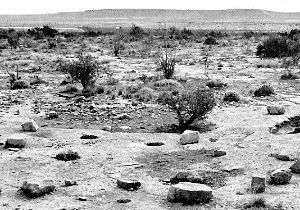

The colorfully named Squawteat Peak site (41PC14) is located in central Pecos County in the shadow of Squawteat Peak, a prominent cone-shaped limestone hill rising some 300 feet above the surrounding desert floor. It is known for its wickiup and tipi rings–all that remain of shelters constructed by prehistoric hunter-gatherers at the site hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years ago. Although the site is sparsely vegetated, and in some areas lying on bare bedrock, the area supports an abundance of natural resources. A variety of useful plants, including lechuguilla, sotol, cacti, and mesquite are present today as they likely were in the past. Flint resources are also abundant in nearby natural outcroppings. Whether drawn to the site by these resources or the dramatic peak looming overhead, prehistoric hunter-gatherers returned to Squawteat Peak again and again over a period of as much as 6000 years.

Squawteat Peak was first examined by the Archaeology Section of the State Department of Highways and Public Transportation (now TxDOT) during mitigation of I.H. 10 in the summer of 1974. The planned expansion of the highway cut across the northern limits of the site, and a large burned rock midden was located within the proposed right-of-way. TxDOT conducted a surface collection of the area and excavated the midden and its immediate vicinity under the field direction of Gary Moore.

Wayne Young and Wayne Belyeu of TxDOT revisited Squawteat Peak in early 1980 to make a topographic and feature map of the portions of the site that had not been destroyed by the highway expansion. Much vital information had been lost since the excavation, and Young hoped to tie together field records from the earlier work with new data derived from the mapping project in order to produce a meaningful report on the site. He published the results of this effort in 1981.

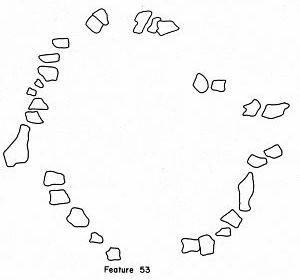

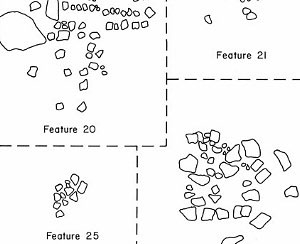

The most important features identified during the investigations of Squawteat Peak are 14 clusters of stones interpreted as wickiup and tipi rings. They range from 2 to 4.5 meters (roughly 7 to 15 feet) in diameter and most are roughly circular in shape. The stones in the 9 wickiup rings (those less than 3 meters in diameter) would have been used to bolster the branch supports of small brush shelters. The 5 larger rings may have supported large wooden poles for tall, hide-covered tipis.

Wickiup and tipi rings are not common in most of Texas and rarely appear in the numbers seen at Squawteat Peak. One of the only other sites reported in Texas with such a large number of stone rings is the Infierno site in the Lower Pecos region. Infierno has many more stone rings than Squawteat Peak: 120 wickiup rings and 7 tipi rings in all. Based on the large size of the tipi rings, the site was likely occupied during the Historic Period, when Native Peoples had access to horses and could transport much larger wooden support poles from camp to camp. (Learn more about the Infierno site in the Native Peoples section of Plateaus and Canyonlands).

In the Big Bend area and eastern Trans-Pecos, numerous structural remains relating to the Cielo Complex have also been documented. Although apparently serving the same support function, stone circles of Cielo structures often had several courses of rocks, clearly showing that these were wall bases.

Squawteat Peak also contains four burned rock middens—the trash heaps resulting from ancient cooking events. The largest measures 11 by 13 meters (roughly 36 by 42 feet), and is actually composed of six smaller overlapping middens. The other three middens are considerably smaller, ranging from 6 to 6.5 meters in diameter (roughly 19 to 21 feet). These middens—consisting of firecracked rock no longer suitable for containing heat, ash, and other debris removed from the cooking pits—were probably used to bake starchy plant foods like sotol and lechuguilla in large quantities. They would have begun to accumulate after anywhere from a few to a few dozen cooking events, over a period of decades to thousands of years.

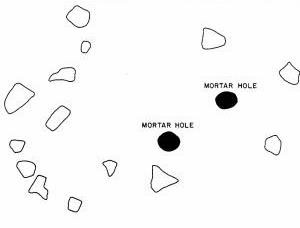

Other features recorded at Squawteat Peak include burned rock hearths and mortar holes that have been worn into the exposed bedrock of the site. Some of the mortar holes have been ground to a depth of at least 30 cm (12 inches), suggesting repeated use of them over a long period of time. They may have been used with wooden manos to grind plant food, such as cactus fruit (or tunas), or pound mesquite pods into meal, since metates are less suitable for these tasks.

An additional area of note at Squawteat Peak is an outcropping of Solomon Peak chert (a type of Edwards chert) on the edge of the site. This area has no cultural features, but its surface is covered with fine-grained chert nodules and flake debris. It was likely used as a lithic procurement and initial-stage knapping area by the people who visited the site. According to archeologist Michael Collins, who surveyed the site in the 1980s prior to the proposed construction of oil rig roads in the area, use of this quarry goes back to at least the Late Archaic period, if not further, based on several Shumla projectile points that he recovered during his investigation.

Surveyors working with Collins re-mapped the features recorded by Young and Belyeu using digital transits and found that the sitemap from the 1981 TxDOT report did not accurately depict their locations. Unfortunately, the company sponsoring the later survey went bankrupt; because the transit data was not saved, a revised map could not be made. Without an accurate site map of Squawteat Peak, it is impossible to determine the relationships of the site’s features to one another.

The chronology of the features at Squawteat Peak is also difficult to determine. The largest burned rock midden was the focus of the 1974 excavation and is the only area of the site that has been radiocarbon dated. The midpoints of the dates taken from the area around the midden range from A.D. 900 to 1530, and the midden itself (technically, the last use of the midden) dates to approximately A.D. 1300.

No ceramics were found that could help date the site's features, but 1 Langtry dart point, 1 Montell dart point, 1 Ensor dart point, and several unclassified arrow points were recovered from the wickiup and tipi rings. The middens produced 1 Pandale dart point, 1 Uvalde dart point, 1 Val Verde dart point, 2 Langtry dart points, 2 Ensor dart points, 1 Frio dart point, 1 Paisano dart point, 4 unclassified dart points, 2 Livermore arrow points, 3 Perdiz arrow points, and 2 unclassified arrow points.

These projectile points date the site’s features to the Early/Middle Archaic, Late Archaic, and Late Prehistoric periods. However, most of them appear to come from secondary contexts as a result of animal activity and sheetwash over the site, making it difficult to determine what time period each feature belongs to and which, if any, are contemporaneous.

Because the investigations of Squawteat Peak have been so limited, few artifacts have been collected from the site. Other than the previously mentioned projectile points, only 1 arrow point preform, 68 bifaces, 91 scrapers, 73 cores, 67 modified flakes, 6170 unmodified flakes, 1 polishing stone, 1 limestone abrader, 1 incised stone pendant, and 1 shell pendant were recovered.

Plant and animal remains are equally sparse. The 1974 excavation produced no plant remains and only seven identifiable bones, belonging to white-tailed deer, domestic goat, Mexican ground squirrel, and raccoon. It is not clear which, if any, of these animals were consumed by the prehistoric visitors to the site. Subsequent investigations yielded no additional clues about the diet of the people of Squawteat Peak, leaving this topic open for speculation. The burned rock middens make a strong case for the consumption of lechuguilla or sotol and the mortar holes suggest that mesquite beans, tunas, or other plant foods that require grinding were consumed. Various species of edible grasses are also available in the area, as well as rabbit and hare.

Though it is unclear when earth ovens were used and wickiups and tipis were built at Squawteat Peak, the site must have been an attractive place for the prehistoric people of the eastern Trans-Pecos who returned to it for thousands of years to harvest its resources. Very little work has been done at Squawteat Peak, and Collins and other researchers believe that there is potential for additional data recovery at this significant site that could help shed light on how its people lived.

Credits and Sources

This section was contributed by Carly Whelan, based on reports by Wayne Young and others, as cited below. Michael Collins also contributed helpful insights.

Miller, Myles R. and Nancy A. Kenmotsu

2004 Prehistory of the Jornada Mogollon and Eastern Trans-Pecos Regions of West Texas. In: The Prehistory of Texas, edited by Timothy K. Perttula, pp. 205-265. Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

Young, Wayne C.

1981 Investigations at the Squawteat Peak Site Pecos County, Texas. Texas State Department of Highways and Public Transportation Highway Design Division, Publications in Archaeology Report No. 20, Texas Antiquities Permit No. 57, Austin Texas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|