Critical to the success of any radiocarbon dating effort is a thoughtfully conceived sampling strategy. Planning ahead, the archeologist can articulate questions to address, identify datable material types recovered from excavation (or pulled from curation), and select the most appropriate samples for dating. This approach allows efficient use of the radiocarbon budget and gives the archeologist confidence that the dating program will yield well-targeted chronological data in support of research evaluation and interpretation.

Prior to the development of AMS for radiocarbon dating in the early 1980s, researchers were limited by the large sample size required by conventional measurement methods (direct counting of radiocarbon decay). Back then archeologists often could not be choosey about materials they wanted to radiocarbon date because maximizing sample size was a driving concern. Consequently, they sometimes amassed charcoal fragments from large features like middens or scattered across occupation areas measuring meters across. Additionally, there were few specialists able to identify the species of charred materials. Legacy dates were often reported with little information beyond that “charcoal” was dated from a general context.

The advent of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating triggered a sampling revolution in radiocarbon dating—archeologists suddenly could select from much smaller fragments of archeological materials, such as tiny pieces of charred plant remains (and uncharred remains in arid and sheltered contexts). With the high-resolution measurement capabilities of AMS, context and sample identification became critical. This exhibit section reviews some of the critical sample selection factors that researchers should consider when developing a radiocarbon dating strategy.

Context and Research Goals

What does the archeologist hope to learn about the archeological site, feature, or artifact through radiocarbon dating? The easy answer is “how old it is.” The more complex answer is that it depends on the dating goal(s). Archeologists often aim to use radiocarbon dating to address broad cultural patterns across time and space. This can include the dating and duration of a cultural period and the timing of use of a particular technology or subsistence strategy. Whether seeking to date cultural patterns or a single event, an archeologist should select radiocarbon samples that can be linked convincingly to the targeted event (the event or pattern they are trying to date). This requires careful consideration of the actual event the sample dates, the research questions, and the sample context.

An excellent example of good security between a sample and its context is an articulated animal skeleton (intact bones still attached or adjacent). Articulated skeletons suggest that the animal died shortly before being deposited in a fully fleshed form, and that there was little disturbance to the deposit in which the skeleton is found. Another good example of outstanding contextual security is organic residue adhering to the interior surface of intact or refit pottery vessels, which can be expected to date the last time that the vessel was used and, like the articulated skeleton example, may indicate that little stratigraphic disturbance occurred since the vessel was deposited.

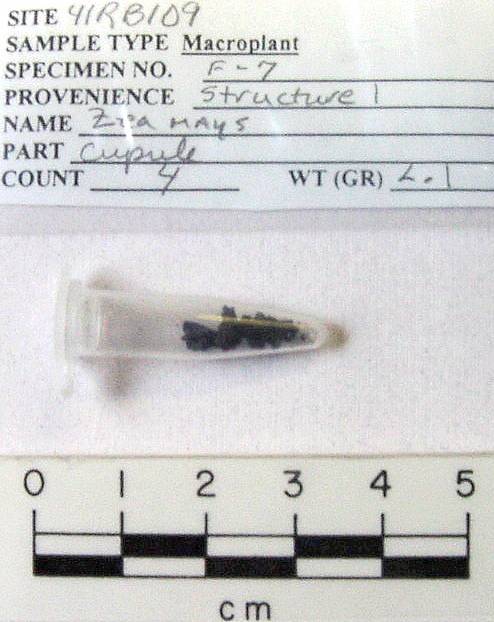

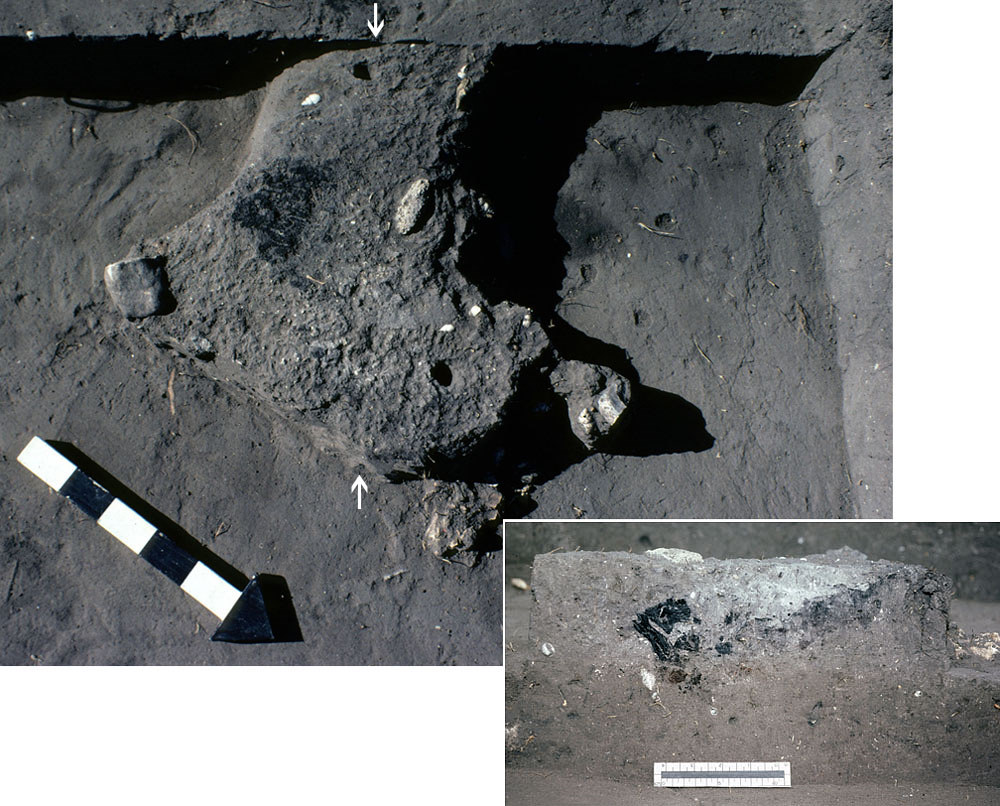

Discreet deposits of organic materials also make good candidates for dating, such as charred plant materials or other materials found within a pit feature that appears to represent a single-use event (multiple dates can help confirm this). Short-lived plants closely associated with a deposit or behavior of interest also make exceptional candidates for radiocarbon dating.

Short-lived Plants versus Old Wood

Some of the best materials to date are short-lived plant remains that have a secure relationship to the archeological context or research question. By dating short-lived plants or plant parts (such as leaves, seeds, and twigs) the archeologist can avoid the well-known old wood effect. Caveat: when considering dating small, dense plant materials like nuts, seeds, and even tiny charcoal chunks, the archeologist should be mindful that such materials can be introduced into unconsolidated archeological deposits by burrowing animals or gravity.

While wood charcoal is durable and relatively abundant in the archeological record, some trees can live for hundreds of years, and a chunk of wood from the center of such a tree may date hundreds of years older than the outer rings, which formed later. Additionally, in an arid climate dead wood may be lying around for many decades or even centuries before being gathered for fuel wood. Thus, if only wood charcoal is available to date at a site, the archeologist should attempt to date charred twigs or smaller limbs, called round-wood. Roundwood is more likely to date closer to the targeted event than the central heartwood. Even better candidates for dating are annual seeds, nut shells, fruits, or leaves. An archeobotanist can pick out short-lived samples that are best suited to dating from matrix samples (sediment samples) or from targeted radiocarbon samples (spot samples). Archeobotanists can also often identify tree species by looking at wood charcoal under magnification and consider the lifespan of those species.

By dating short-lived “economic” species such as food remains, instead of the wood used to fuel the cooking fire, the archeologist can address questions about the use of specific food plants such as agave or corn. By sampling and dating fuelwood and economic species from a cooking feature context, for example, the archeologists can check for consistency between the dates. If the dates are in agreement the archeologist can be more confident that they have a good date range for the targeted cooking feature. If the dates are not in agreement, then perhaps more samples need to be dated from the feature to interpret its period of use.

Sample Challenges

Challenges for several common sample material types are well-known. Some of these have corrections that can be made to offset their inherent problems, but still may be best to avoid if other sample materials are available to date. Problematic materials include aquatic organisms or animals that derived a large part of their diet from aquatic environments and therefore likely suffer from marine or freshwater reservoir effects (see In the Environment). Another common problem is the old wood effect, discussed above. While bone can be an excellent material to date, problems with poor collagen preservation in old or degraded bone can make obtaining dates difficult or impossible (see In the Lab).

Contaminated samples are another concern. Contamination can occur in the sample’s depositional environment or occur after the sample is collected. Inadequate pretreatment, conservation treatments like coatings, glues, and consolidants applied to curated artifacts, and mold growth from improper drying and storage are a few examples of potential sources of contamination. Materials suspected of contamination should be avoided for dating when less-problematic samples are available. Archeologists should make explicit any suspected problems with sample materials and any attempts to correct them (such as through reservoir corrections or removal of conservation treatments) when publishing assay results.

Replicating Assays

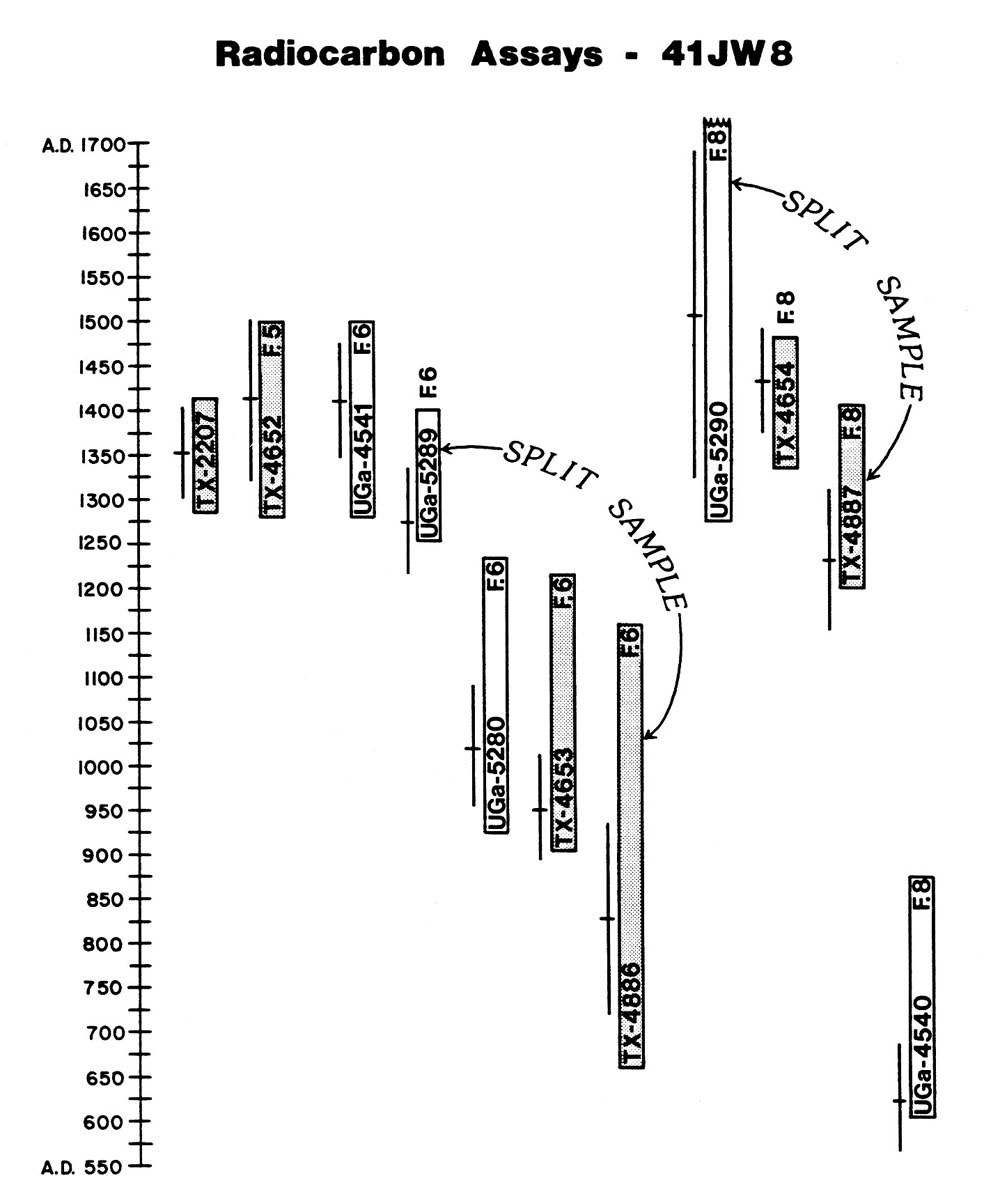

A good way to increase confidence in dates is to replicate assays—that is, date the targeted event more than once to check the accuracy of dates. Replication can be done by splitting samples and sending them to different labs, using different pretreatment methods on a split sample, or by dating several different material types associated with the same event and context. Replication can help identify mixed deposits, reservoir offsets, effects of different pretreatment methods, interlaboratory error, and the reuse of older materials. In addition, having multiple dates from the same single-event feature may allow a more precise date to be generated using statistical combination tools, such as R_Combine in OxCal. How many assays should be replicated? Common sense holds that the answer will depend on the problem at hand, but replication of about 10% of the assays has been recommended for a typical radiocarbon dating program.

Dating Complex Deposits with Multiple Samples

If the archeologist wants to date a deposit that accumulated over time, such as occupation zones, trash middens, and the like, they should expect that the deposit contains materials from many individual use events. For this reason, multiple dates are required to determine the age range of most complex deposits.

For example, many cooking features were used more than once, each use being a distinct event (the cooking episode) which itself was the result of even more distinct events (gathering fuelwood and foods, digging a pit, building a fire, and so on). Although the deposits constituting even a simple feature like a cooking facility represent various behaviors, these activities may be so closely spaced in time that, pragmatically, they can be said to represent a single site-use event. Contemporaneity, however, should not be assumed. Things come to rest within or surrounding cooking features (and other features like pithouses and latrines) that are not contemporary. Features like cooking pits found on stable surfaces, common in upland settings, may have been reused for other cooking events after gaps in use spanning decades, or perhaps even centuries. Such features may also contain items that date long after or before the cooking event(s), such as trash items discarded decades or centuries later. Conversely, feature deposits may have incorporated much older materials dug up during pit digging. Therefore, if one really wants to understand the timing of the accumulation of interpretively important features and deposits, it will require targeting multiple events and sample materials.

Dating Collaboration

Most archaeological research is a collaborative endeavor. Radiocarbon dating should be as well! Mention has been made of the importance of working with archeobotanists to identify and help select short-lived samples. Another key collaborator is the geoarcheologist investigating site and landscape formation processes as well as other specialists who are often part of a research team, such as zooarcheologists.

Researchers may also greatly benefit from explicitly involving radiocarbon scientists, particularly with larger dating programs and those that involve problematic sample types that require special types of processing. While researchers should always mention such considerations on sample submission forms, personal consultation before dates are submitted is often very helpful. In fact, involving a radiocarbon scientist on the project team from the outset can greatly improve dating results.

Dating as an Iterative Process

Dating programs addressing complex and challenging contexts and research questions almost always unfold over many years. In other words, strategic radiocarbon dating is not "one and done." Often it is a sequential and iterative stepwise process whereby the research team starts with an initial set of assays (and sometimes legacy dates), and then submits additional samples to further explore and fine-tune dating, to cross-check and replicate previous dates, and to address new questions that arise as research unfolds.

Selecting Samples Summary

There is no one-size-fits-all sampling strategy nor will all sites have ideal materials for radiocarbon dating. Developing an effective sampling strategy for each site, research question, or curated collection requires careful and strategic thinking, as well as thoughtful collaboration. A fundamental step is to consider how the sample material relates to a targeted event or behavioral pattern of interest. When possible, consider dating short-lived organisms rather than long-lived ones. Some of the assays should be replicated to ensure data integrity, among other benefits. Submit multiple samples for dating from complex features or occupation zones—few can be dated confidently with a single assay. Whether an archeologist has an ideal selection of samples to choose from or must do the best they can with problematic sample materials, the reasons for submitting a sample should be made explicit during reporting, along with discussion of any potential problems with it and any attempts to mitigate those problems.