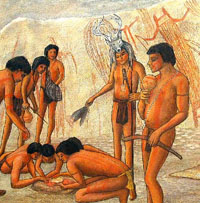

Participants in a ritual anoint themselves

with red paint. The scene is a rockshelter in the Lower

Pecos as envisioned by artist and archeologist Reeda Peel. |

Petroglyphs of various styles also

occur in the Lower Pecos. This example has incised lines

cut by sharp flint tools. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

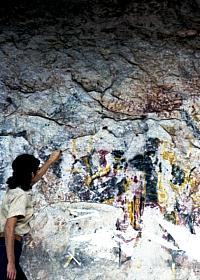

This rock art panel has several styles

of Lower Pecos rock art. Most of the elements including

the large shaman figure just to the right of the sign

board are of the Pecos River style. But the smaller

dark red anthropomorphic figure with down-turned arms

just to the right of the shaman element is of the Red

Monochrome style. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

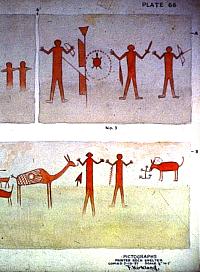

Example of one of Forest Kirkland's

original watercolors of pictograph panels at Painted

Rock Shelter in Painted Canyon, a small side canyon

of the Rio Grande near Comstock, Texas. Most of these

figures are of the Red Monochrome style. Kirkland made

these "copies" as he called them, on July

13, 1937. As subsequent recorders have learned, copying

rock art is a subjective process—what is copied

depends on lighting conditions, condition of the pictographs,

and the eye and skill of the beholder. Photo from ANRA-NPS

Archives at TARL. |

Today the Red Monochrome pictographs

at Painted Rock Shelter persist despite periodic inundation

and fluctuating moisture levels. Photo by Steve Black. |

Close up of Red Linear pictographs.

Photo by Steve Black. |

Pecos River style pictographs in

Rattlesnake Canyon. One of the serpentine "rattlesnakes"

can be seen to the left of the dark shaman figure. Photo

by Steve Black. |

Close up of pictograph of European

man, probably a Spaniard, at Vaquero Alcove. This was

obviously painted by an Indian who had personally witnessed

the man. This style shares strong similarities with

the Plains Bibliographic style. Photo from ANRA-NPS

Archives at TARL.

|

|

The painted images adorning the walls of hundreds

of rockshelters and minor overhangs uniquely define the Lower

Pecos archeological region. The striking and inspiring rock

art is celebrated, photographed, illustrated,

recorded, and studied by hundreds of enthusiasts across the

country and a much smaller number of dedicated researchers.

Typing "Lower Pecos Rock Art" into your favorite

search engine will yield dozens of web pages, many with beautiful

images and some with useful information. (See Credits

& Sources for select links, including several elsewhere on this website.)

Here we will simply provide some examples illustrating

the diversity of the imagery and the kinds of physical contexts

within which Lower Pecos rock art occurs. A few quick points:

"Rock art" includes more than just

pictographs—painted images. Petroglyphs—carved,

pecked, or incised images—also occur in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

So do various kinds of mobile art including painted pebbles.

Pictographs are the most numerous and best known

rock art images in the Lower Pecos. Four main styles were

defined by W.W. Newcomb. From oldest to most recent these

are: Pecos River, Red Linear, Red Monochrome,

and Historic. The oldest, the Pecos River style, is

also the most common, most complex, and most carefully studied.

Many of the Pecos River pictographs are widely

regarded as expressions of shamanistic ritual. As summarized

by Carolyn Boyd and Phil Dering in a 1996 article:

Shamans are found primarily within Native

American societies that rely heavily on hunting and gathering

or fishing … In these societies, the shaman serves

a crucial role as diviner, seer, magician, healer of bodily

and spiritual ills, keeper of traditions, and artist. Acting

as the guardian of the physical and psychic equilibrium

of the society, the shaman, through altered states of consciousness,

journeys to the spirit world where he will personally confront

the supernatural forces on behalf of his group.… Access

to the spirit or Otherworld can be achieved through such

methods as the use of hallucinogenic or psychoactive plants,

fasting, thirsting, blood-letting, self-hypnosis and various

types of rhythmic activities ….

As the article documents, there is clear evidence

of hallucinogenic plants including peyote, mountain laurel

beans (seeds), and datura (jimson weed) in the rock art and

cave deposits of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Controversy has arisen concerning

the specter of prehistoric "drug" use, despite ample

evidence of the ritual and medicinal importance of such psychoactive

plants in many Indian cultures in the New World. Politically

correct or not, the use of these plants was part and parcel

of shamanistic ritual in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands as elsewhere in the

hunter-gatherer world. While ingesting psychoactive plants

can be very dangerous and even fatal, they obviously played

a critical role in certain of the rituals depicted in the

Lower Pecos rock art. The ritual use of peyote continues today

by members of the Native American Church, a traditional religious

practice that has been ruled constitutionally protected by

the United States Supreme Court.

The rock art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands dates to at

least 4,500 years ago and possibly considerably earlier. Within

the past decade or so, chemist Marvin Rowe at Texas A&M

and researchers at other institutions have devised clever

ways of directly dating elements of the paint. As this research

matures, dating will become an important tool in understanding

the evolution and meaning of rock art in the region.

The most comprehensive catalogue of Lower Pecos

rock art is still the work of Dallas artist Forest Kirkland

who with his wife and partner, Lula, visited dozens of rock

art localities across the western half of Texas in the 1930s.

His watercolor renditions of what they observed are often

the sole surviving record of images that have since been destroyed

by time, "progress," and thoughtless vandals. Shortly

after Kirkland first laid eyes on Indian pictographs in the

summer of 1933 at Paint Rock near San Angelo, he dedicated

almost every available moment to saving these fragile, disappearing

images for posterity. Until he died in 1941, the Kirklands

took extended camping and working vacation trips each summer

to remote places in different parts of Texas where rock art

was known to occur, including the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

The Kirklands took a systematic approach to

their work, capturing each grouping of paintings they could

make out on panels of high quality English linen mounted on

heavy cardboard plates. All drawings were done to scale and

were considered "copies" as faithful to the original

as possible. The story of the Kirklands' work and most of

his drawings appear in the 1967 book The Rock Art of Texas

Indians (text by W.W. Newcomb), reissued in 1996 by UT

Press. You learn more about Kirkland's work and see many examples

of his renderings elsewhere on this website—see On the Trail to Lower Pecos Rock Art.

The two leading researchers who study Lower

Pecos rock art today are Dr. Solveig Turpin and Dr. Carolyn

Boyd. Their approaches and interpretations vary considerably.

Turpin, an archeologist by training and former

Associate Director of TARL, has been at it for a lot longer

and takes a more traditional approach to her work. She has

published numerous scholarly articles and book chapters documenting

and interpreting many different aspects of Lower Pecos rock

art including work in northern Coahuila. She also co-authored

and edited several rock art volumes including a beautifully

illustrated coffee-table book entitled Pecos River Rock

Art (with Jim Zintgraff, the leading rock art photographer

of the region). Turpin and Zintgraff are co-founders of the

Rock

Art Foundation, a nonprofit organization devoted to the

preservation and study of rock art.

Boyd, an artist and anthropologist by training

and has pioneered what she calls an ethnographic approach to Lower Pecos rock

art interpretation. She argues that many rock art panels represent

coherent mural-like compositions rather than randomly added

elements as many have assumed. She sees many parallels between

the Pecos River style symbolism and that expressed in the

mythology and belief systems of many living and historically

known cultures in Mexico and the Southwest. Boyd has published

several scholarly articles and book chapters on her work and

has just finished a book that has been published by Texas A&M

Press. She is the Executive Director of the Shumla School, a non-profit educational and research center located on the lower Pecos River. Today Boyd and her collaborators and students continue studying and documenting the rock art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Another important group actively involved in

research is the Rock Art Recording Task Force

of the Texas Archeological Society. The Task Force is devoted to documenting the rock

art of Texas. Each year they concentrate on different localities

and thoroughly record rock art imagery through photography,

mapping, tracing, and illustration, carrying on the work started

by the Kirklands.

Pecos River style pictographs near the mouth

of Rattlesnake Canyon, a side canyon of the Rio Grande.

Photo by Steve Black.

Photographer examines Historic

style pictographs at Vaquero Alcove. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

|

Painted pebbles such as this one

are common in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands but are also known

from south and central Texas. They are almost always

made on smooth, flat, rounded river pebbles. Although

they share some elements in common with pictographs,

they are usually less elaborate and painted in black. From the ANRA-NPS collections at TARL. |

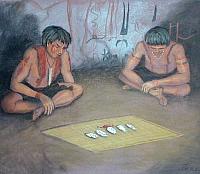

Four painted pebbles and a handful

of Mountain Laurel beans rest on a mat in front of two

men in a painted cave in a scene envisioned by artist

Reeda Peel. |

Close up of Red Monochrome pictograph.

Photo by Steve Black. |

Several of the Red Monochrome figures

at Painted Rock Shelter as they appeared in 1958. Only

20 years after Kirkland, the deterioration of the images

is evident. This shelter is at the bottom of a canyon

just above a spring-fed pool of water. As you can also

see, direct sunlight adds to the problem. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

The dark band obscuring some of the

Red Monochrome pictographs at Painted Rock Shelter is

the high-water mark left by repeated, though infrequent

floods. Photo by Steve Black. |

Close up of an animal figure, perhaps

representing a deer. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

Art history researcher Penny Lindsey traces Pecos River

style pictographs onto a clear sheet of acetate in 1963.

Direct tracing is thought by some to be the most accurate,

albeit cumbersome, method of copying pictographs. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

Vaquero Alcove is known for its Historic

style pictographs depicting a Christian church and a

man dressed in European-style clothing. These were painted

on the curving canyon wall protected only by shallow

overhang. Being near the canyon bottom, the rock art

panel is periodically covered by flash floods. Photo

from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL. |

|