Natural Setting: A Rocky Oasis in the Desert

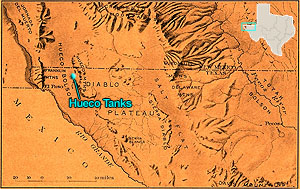

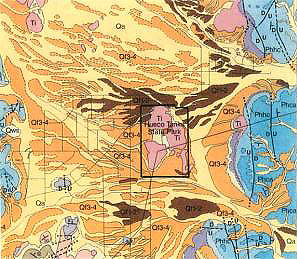

The abundance and variety of resources at Hueco Tanks have attracted people to this desert setting throughout prehistoric and historic times. Within and at the base of the huge rock outcroppings—actually, four hills of stone—are special habitats, or econiches, where trees, plants, and animals normally found in more moist environs or at higher elevations, thrive. A variety of conditions foster this environmental oddity, but rocks and water are the key elements. The rocks of Hueco Tanks were born millions of years ago as an underground mass of hot magma. The molten rock pushed upward and cooled beneath a layer of limestone. Over millions of years, wind and water wore away the limestone, exposing and sculpting the igneous rock to form the shapes we see today. Hollows in the rock (huecos) capture precious water during rainy periods—particularly the monsoons which typically occur in the late summer months. Rock crevices, seasonal ponds, wetlands, and man-made dams or catchments—some deriving from prehistoric times—store water as well. These " tanks" of water, so rare in the desert, have made Hueco Tanks a stopping point and haven for people and wildlife for thousands of years. Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site is located in the southeast part of the Basin and Range physiographic province which is characterized by isolated, nearly parallel mountain ranges separated by broad flat basins, or bolsóns, as the Spanish called them, meaning large purse. The site is located near the north end of the Hueco Bolson, a basin that extends along the Rio Grande for about 130 miles from southeast to northwest. The northern Hueco Bolson is flanked on the east by the Hueco Mountains, which actually are the dissected west edge of the Diablo Plateau. The main escarpment lies about 1 mile east of Hueco Tanks, and outlying foothills are located 2 to 3 miles to the northwest, west, and southwest of the state historic site. The west margin of the northern Hueco Bolson is defined by the Franklin Mountains, located around 24 miles west of Hueco Tanks. Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site is situated on the sloping surface of accumulated sediments that have eroded from the west flank of the Hueco Mountains. Four rock masses—North Mountain, East Mountain, East Spur, and West Mountain—are the dominant topographic features in the park. Sheltered between the hills are basins on the south and west. Deep canyons cut into the northwest side of East Mountain (Mescalero Canyon) and the west side of North Mountain. The fractured and eroded rock hills also contain many smaller cracks, overhangs, and natural hollows, or huecos, for which this landmark is named. Geology and SoilsHueco Tanks is a laccolith-like (domed) igneous intrusion composed of porphyritic syenite, and was formed 35 million years ago. Between 30 and 24 million years ago, faulting formed the basin and range topography that characterizes the region today. Downthrown fault blocks underlie basins like the Hueco Bolson and are adjoined by uplifted fault blocks that make up ranges like the Hueco and Franklin Mountains. Over the last 25 million years, sediments were eroded from these mountain ranges and deposited in the Hueco Bolson. Known as the Santa Fe Group, they consist of colluvial, alluvial fan, water-laid, and lake deposits. Recent deposits on the Hueco Bolson and Tularosa Basin are designated as Quaternary sedimentary units Q1 through Q4. The two deepest deposits—Q1 and Q2—pre-date human existence in the region. Archeological materials have been recovered from the upper part of Q3 and the base of Q4. The windblown sand that composes Q3 was laid down around 7,000 years ago; deposition ended around 1,100 years ago and the surface became stable. Archeological sites and features that are 1,000 years old or older may be buried in Q3 deposits but all materials younger than that age sit on or near the surface of the Q3 sands. For this reason, many of the archeological sites in the region are visible on the ground surface. Q4 consists of dune sand loosened when grasses were removed by overgrazing around 100 years ago and redeposited by wind. In the Hueco Bolson, materials for making chipped stone tools, grinding tools, and pottery are available from a diverse array of sources. Rocks suitable for chipping can be found in bedrock formations, in alluvial fans, along arroyos and streams, and in basins. Chert is the most commonly available chippable rock near Hueco Tanks. Chert outcrops within 5 miles of the Tanks reportedly show evidence of prehistoric use as quarries. Rock for making chipped stone tools also is available from relatively distant primary sources such as in the foothills of the southern Sacramento Mountains. The Franklin Mountains 24 miles to the west contain chert as well as quartzite and rhyolite. Soledad rhyolite is available in the southern Organ Mountains. Obsidian is the only commonly chipped stone that does not occur in the rock formations of the Hueco Bolson region. The closest major obsidian outcrops are located in north-central New Mexico on Mount Taylor and Mount San Antonio, and in the Jemez Mountains. Secondary sources of chippable stone in the Hueco Bolson are more widely available and include gravelly slopes, alluvial fans, arroyos, gravel bars on streams, and erosional basins. Present-day and ancient gravel deposits of the Rio Grande constitute major secondary sources. Where the original Rio Grande channel ran through the Hueco Bolson, gravel deposits of the Camp Rice Formation contain locally-derived rhyolite, chert, and quartzite, as well as obsidian and other rocks that originate in the upper Rio Grande drainage basin. These gravels are exposed along limited areas of arroyo walls, fault scarps, and eroded slopes. Gravels also are exposed on the basin floor in blowouts and other eroded areas, but are predominantly small. Rock for making ground stone tools can be obtained from many geologic formations in the Hueco Bolson. Most accessible to the park is porphyritic syenite, which makes up the rock hills of Hueco Tanks. Limestone is available from the Hueco Mountains and outlying foothills, located 1 to 3 miles from the Tanks. Sandstone can be obtained from the Bliss Formation in the Hueco Mountains; the closest outcrop is around 12 miles south of Hueco Tanks. Granite is available from isolated outcrops that adjoin the south end of the Hueco Mountain range, ca. 18 miles south of Hueco Tanks. Clay suitable for pottery making is available in a variety of settings across the Hueco Bolson, including playas, terraces of the modern and ancient Rio Grande, and distal alluvial fans. Although a number of clay samples have been submitted for chemical analysis, few have been directly matched to prehistoric pottery. The array of elements in the prehistoric ceramics of the Hueco Bolson suggests that they were made of clays derived from igneous rocks, however. Preliminary chemical analyses have indicated that clay from the igneous intrusion named Cerro Alto (located 4 miles northeast of Hueco Tanks) was used in ceramics on sites in the eastern Hueco Bolson, but this remains to be substantiated. The soils in Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site are composed of porphyritic syenite, quartzose sand, and sediment derived from limestone. Mapped associations are Pajarito, Simona, Wink, and Mimbres; some nearby areas are identified to the Agustin association. These soils developed on alluvial fans and are friable, calcareous, and moderately alkaline. Mimbres association deep silt loam has developed in shallow watercourses and playas, and is mapped in three areas of the park: along the south boundary fence, on the east side of North Mountain, and on the northeast side of East Mountain. For desert farmers some 850 years ago, Mimbres soil, with its higher capacity for moisture retention, was critical to growing corn, beans, and other crops. Water and Its Surface DistributionNatural water sources in Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site consist of alluvial fan drainages, marshy areas where water accumulates, runoff from the rock hills, and natural rock reservoirs. Additional water sources that have been created by humans are discussed in the section, Weaving the Story. Runoff water from the west flank of the Hueco Mountains is delivered to Hueco Tanks by a network of channels that drain the alluvial fan. The Tanks are positioned between large arroyos to the north and south, which carry runoff from major canyons in the range. A smaller stream once flowed between North and East Mountains, as indicated by freshwater snail shells recovered at depth in the present-day arroyo. Channels on alluvial fans carry runoff for some time after rains; moisture is retained in soils near them and in areas where the water ponds. Drainages originating on the west side of the Hueco Mountains flow toward the center of the Hueco Bolson, where the water eventually is lost to evaporation.

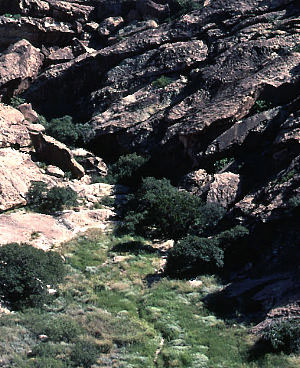

The porphyritic syenite hills that comprise Hueco Tanks collect rainwater in cracks. Carried downward by gravity, the water carves shallow channels into the rocks, marked by dark stains. When channeled water reaches the base of the rock hills it creates patches of moist soil and small ponds that support mature trees and plants —water-lovers such as willow, cottonwoods, and ferns. During the rainy season the channels carry flows ranging from rivulets to waterfalls. Similar channels enclosed in the rock hills are evidenced by audible trickling and dripping after rains.

VegetationThe vegetation of the Hueco Bolson is classified generally as Chihuahuan desertscrub. Distribution of modern plant communities in this region is controlled by moisture, temperature, and elevation: desertscrub grows on the basin floor, grasslands on intermediate surfaces, and woodland communities at higher elevations. Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site is on an intermediate surface that is covered by desertscrub and degraded desert grassland, but because its igneous-derived soils hold water more effectively than soils in the surrounding area, the plant community in the state historic site is diverse and includes a number of woody and water-dependent species typical of desert, mountain, aquatic, and grassland habitats. The level terrain surrounding the igneous outcrops is dominated by a desertscrub/grassland community including creosotebush, honey mesquite, tarbush, soaptree yucca, ocotillo, lechuguilla, sotol, prickly pear, and other cacti. Grama grasses, goosefoot, and amaranth grow near the rocks, while fourwing saltbush and threeawn and other grasses are widespread on the flats. Many of these plants would have been useful to native peoples. Trees are concentrated along the base of the rock hills where runoff forms small water catchments, and in narrow canyons that provide greater moisture due to increased shade and lower evaporation. They include netleaf hackberry, Texas mulberry, Mexican buckeye, Arizona white oak, and rose-fruited juniper. The juniper, oak, and hackberry are relict components of the woodland that covered Hueco Tanks and similar locations in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. Water-dependent plants are found in moist soils near dams and seeps, and in shaded fissures. These include leafy pondweed, hairy pepperwort, slender rush, Rio Grande cottonwood, and Goodding willow. . Hueco Tanks contains several plants rarely found in the state, such as the only known population of Erect colubrina (Colubrina stricta) in the United States (although this shrub of the buckthorn family occurs in Mexico). A tall, spindly shrub of the mallow family (Abutilon mollicomum) also is found at two locations in the state historic site, which may represent its only occurrence in Texas. Mosquito plant (Agastache cana) of the mint family is confined primarily to rocky slopes, crevices, and ledges in the western Trans-Pecos and adjacent New Mexico. This perennial herb is quite limited in distribution but is fairly widespread at Hueco Tanks. Animals |

|

From out of the dust to life. So-called "fairy" shrimp, among the tiniest of creatures in the park, seasonally thrive in the huecos, providing food for other wildlife. Lying dormant in the dusty hollows during dry periods, these near-microscopic crustaceans burst back to life after periods of rainfall, attracting predators such as golden eagles and lizards. At left, a dry hueco, perhaps containing hundreds of dormant shrimp; center, a rain-filled hueco teeming with shrimp such as the Branchinecta-packardi, right. Photos credits: left, Susan Dial; center, Centennial Museum, El Paso; right, Wikipedia. | ||