|

The ruggedness and isolation of the

countryside west of Austin did not deter settlers from

establishing small farmsteads and communities in the

hills during the 1860s and 1870s. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

An enterprising clerk and merchant,

Ernst Hallman moved to the hills to raise sheep in the

1880s, despite multiple physical disabilities. Photo

circa 1875, courtesy of the Travis County Bar Association

and Senator Ralph Yarborough.

|

"In small things forgotten…."

An array of objects and mementos left behind in a turn

of the century farmstead range from the mundane—an

orange plastic ice token from a company operating in

Austin in the 1880s—to the more poignant, a brass

bicentennial badge marked with the dates 1776 and 1876.

|

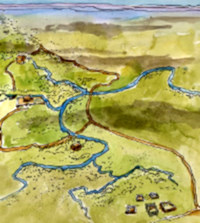

Fertile terraces along creeks provided

deep soil for growing crops on a small scale. The narrow

valleys, bound by limestone bluffs and low hills, provided

a measure of confinement for domestic animals such as

hogs.

|

|

|

The old log house had been well lived in by

more than four generations of families, some of the first

settlers to venture into the hills west of Austin. But after

roughly 100 years of standing up to hard use and the elements,

it had fallen into ruin, its roof caved in, walls sagging,

and floor rotted out. It was a fairly common sight in the

Texas Hill Country, where traces of our pioneer past—fences,

stone walls, houses, and farmsteads—now go largely unnoticed

and, eventually, fall to ruin, the victims of natural processes

or, more commonly now, bulldozers and development.

But this particular house was to be spared,

the landowners intrigued by local stories about its history

and moved by a feeling of responsibility to preserve the heritage

of their land. When they set out to restore it, they did not

merely hire a carpenter but rather a team of specialists to

uncover its history and rebuild it accordingly: archeologists

from the University of Texas at Austin, an architect specializing

in historic structures, even a landscape restorationist. It

was through the efforts of this group that the Doeppenschmidt-Haas

house was brought back to life, the story of a young boy raised

in the house at the turn of the twentieth century was heard,

and the traces of a small pioneer community in the hills west

of Austin were drawn together.

The stories embodied in the now-abandoned farmsteads

and structures are of a people whose everyday lives, by modern

standards, are heroic. The study of these families and the

loosely connected settlement along Barton Creek provides a

record of a little-appreciated time in Texas history. At the

turn of the twentieth century, sweeping changes occurred in

Texas cities with the advent of electricity, communications

systems, and better transportation. In many of the rural areas,

however, time was frozen. Families grew and canned much of

their own food, cooked in fireplaces and wood-burning stoves,

and hauled water for drinking and laundry. Homes were lit

by kerosene and Aladdin lamps. Children attended school periodically,

depending on crop planting and harvest times, and went to

poorly funded institutions referred to as the "mountain

schools."

As a rule, life continued to revolve around

the seasons and the land and the vagaries of nature. Modernization

came relatively late to the hill country, and even then, changes

were gradual. Well into the 1930s and 1940s, some families

continued living what was, in essence, a pioneer existence.

Pieces of the Puzzle

Archeologists from UT Austin survey rocky

hillslopes surrounding a historic site to determine its perimeters

and to recover any artifacts that might help establish its

age.

When archeologists from TARL at UT Austin began

to survey the area, the landowners had already identified

several historic sites. There was the log house that once

belonged to the Haas family and, several miles away, a picturesque

stone building thought by some to have been a country store.

Still more remote was a small cemetery, its few remaining

markers toppled, the walls around the graves reduced, in some

cases, to piles of rubble. There were other historic-era sites

scattered across the property: remnants of stone foundations,

a log crib, a hand-dug well, scatters of purpled glass and

rusted metal. The task at hand was to gather and analyze evidence

from each site, interview neighbors and other informants,

and investigate early records to try to learn more about the

families who once had lived there and who, for the most part,

had vanished.

Bringing the pieces of the puzzle together depended heavily

on deed and court records and recollections of area residents:

When was the area first settled? Who were the settlers and

why did they take on what must have been, at best, a hard-scrabble

existence on the land? Were the families that lived on the

sites related—or were the sites even in use at the same

time? Other information was derived from the physical evidence

itself—the building remains and artifacts left behind

by the former occupants.

Settlement West of Austin

On a larger scale, the hilly area west of Austin

appears to have been settled predominately in the latter quarter

of the nineteenth century, when threats of Indian incursions

had abated. Deed records indicated that although tracts of

land were patented as early as the 1850s, most were left in

a natural state and used as reliable sources of fence posts

and firewood. Within the upper Barton Creek region, archeologists

found that the earliest sites were situated close to a permanent

water supply and fertile valley land. By the turn of the century,

as machine-drilled wells and wire fencing became available,

additional farmsteads were established in upland areas. This

movement also indicated a change in livelihood from small-scale

subsistence farming to larger stock-raising operations requiring

upland grazing areas and more acreage for crops.

One way of understanding a cultural landscape

is through its architectural elements: remnants of physical

structures and fences retain the imprint of the builders and

sometimes can reveal aspects of their origins. In the area

west of Austin, early European American settlers left distinctive

marks on the land. Their diverse cultural backgrounds are

signaled in the fine examples of folk architecture, the varied

complex of stone and log fences, the remains of upland farmsteads,

and the mortuary traditions reflected in the small cemeteries.

In the sections below, we look at several of the more interesting

examples.

|

A winding wagon road once connected

family farms in this small Barton Creek community in

the hills west of Austin, circa 1870. Painting by Charles

Shaw.

Click images to enlarge

|

Hillside cemetery—the final

resting place for many of the early settlers.

|

Clear water gushes through the hollows

and creek beds in the limestone hills, fed by underground

springs and periodic rains.

|

TARL archeologists survey along a

road in the project area. Left, Dr. Tom Hester, right,

Paul Maslyck.

|

A deep, hand-dug well, lined with

cut limestone, provided water at an upland farmstead

during the early 1900s. It is now the only surviving

structure on that farm. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

|