Animal Bones and Teeth

Given the scarcity of stone in the Coastal Prairies and Marshlands it is no surprise that the native inhabitants made many objects out of animal bone as they did of shell. Animal bones were used to meet a range of needs including, but not limited to, formal and informal tools, musical instruments, and sacred talismans. Animal bones were easy to come by because coastal natives exploited many different critters from marine fish and reptiles to prairie grassland and riverine woodland artiodactyls (deer and bison) for food and leather.

Examples of the use of animal bone as a raw material from central and upper coastal sites attest to the skillful ability of coastal natives to adapt to available coastal resources. While there are known examples of similar uses of animal bone from the lower coast, few are from excavated and well-documented contexts. There are many bone tools and ornaments documented along the central and upper coast including “ordinary” objects that are shared in common with inland sites, such as bone awls made from deer bone, flaking tools made from deer antler, and bird-bone beads. More telling are examples of bone objects that are rare or absent inland beyond the coastal zone.

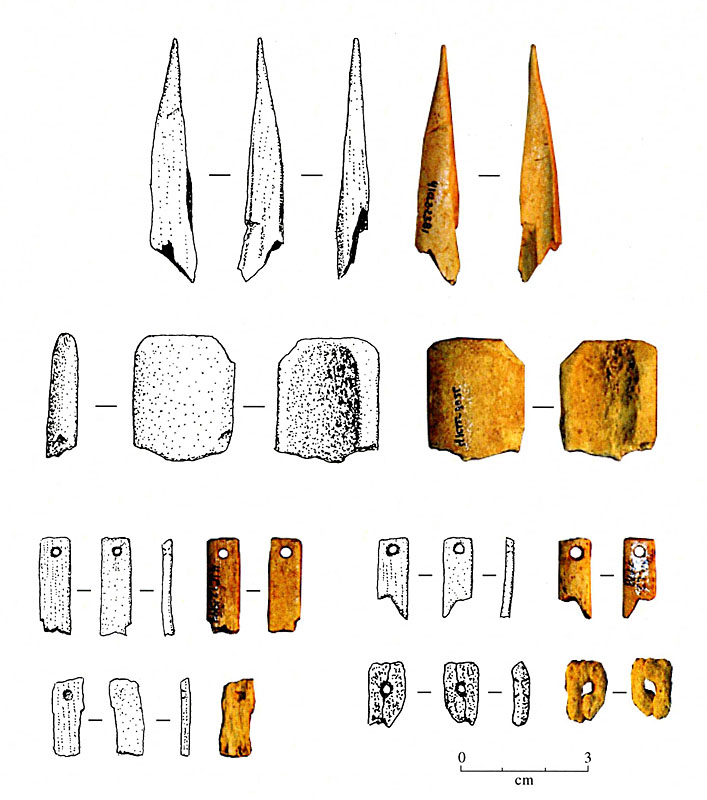

The most common and characteristic coastal bone tools are various forms of sharpened bones thought to have been used as the points of darts and spears, examples of which have been found along the entire coast. The earliest grave at Mitchell Ridge on Galveston Island, that of the adult male, held seven socketed bone points and four unworked distal ends of deer metapodials thought to represent manufacturing blanks for the socketed bone points. Virtually identical bone points have been documented in Archaic and Early Ceramic contexts in the Galveston Bay and Brazos delta areas of the Upper Texas Coast. To the east, socketed bone points are characteristic of the Tchula culture of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Louisiana coastal zone.

Socketed bone points are made from the distal ends of deer metapodials (foot bones) and range in length from 4 to 10 centimeters. They were manufactured made by grooving and breaking off the proximal end of the metapodials, grinding the shanks to a point, grinding off the distal articular surfaces, and reaming out the distal ends to allow the assertion of a presumably wooden shaft. Globs or traces of asphaltum hafting cement are typically found in the interior of the points. The socketed points may have been part of fishing spears or harpoons; but, although they seem somewhat unwieldy, they could have served as substitutes for chipped-stone dart points used for hunting and warfare.

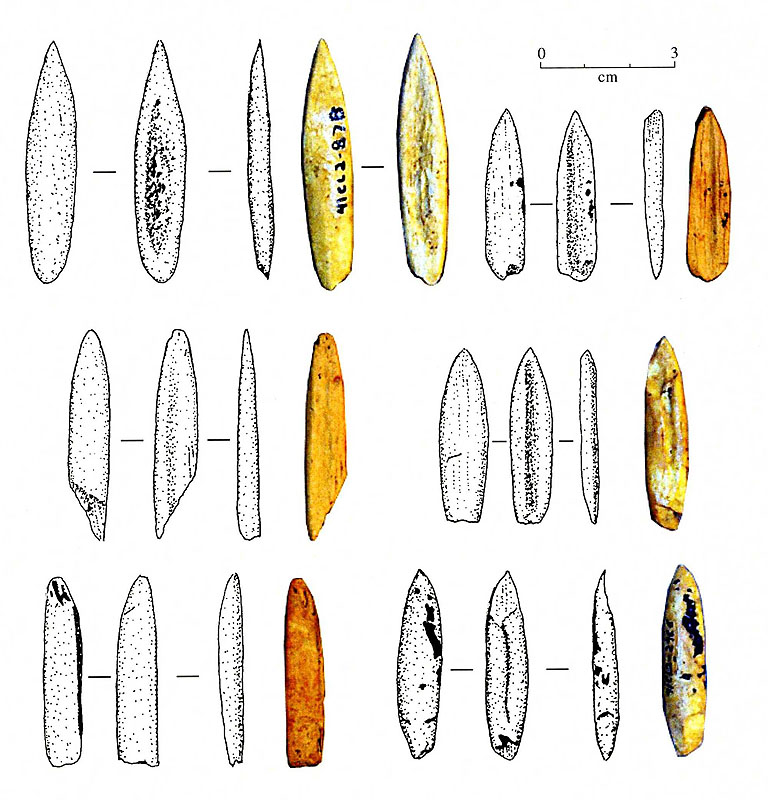

The Guadalupe Bay site yielded numerous examples of a different form of bone point, finely sharpened lanceolate points made from mammal long bone fragments, probably deer. Most of the lanceolate bone points from this site at the head of San Antonio Bay are sharply pointed at one end, the opposite being more gently rounded. Traces of asphaltum adhered to several of the bones. There were also two other types of, “large” bone points at the Guadalupe Bay site that resemble, and may in fact be worn fragments of, socketed bone points, and socketed point manufacturing debris. These were fashioned from deer metapodial bones, and in one case a deer femur, using the groove and snap technique and grinding. A variety of other pointed bones and fragments from this site suggest that sharpened bones were used as projectile points, awls, and perhaps as gorgets. The latter are small thin bipointed pieces that resemble fishing gorgets tied to a line in the middle of the shaft and used as baited hooks in the eastern Gulf along the Florida coast.

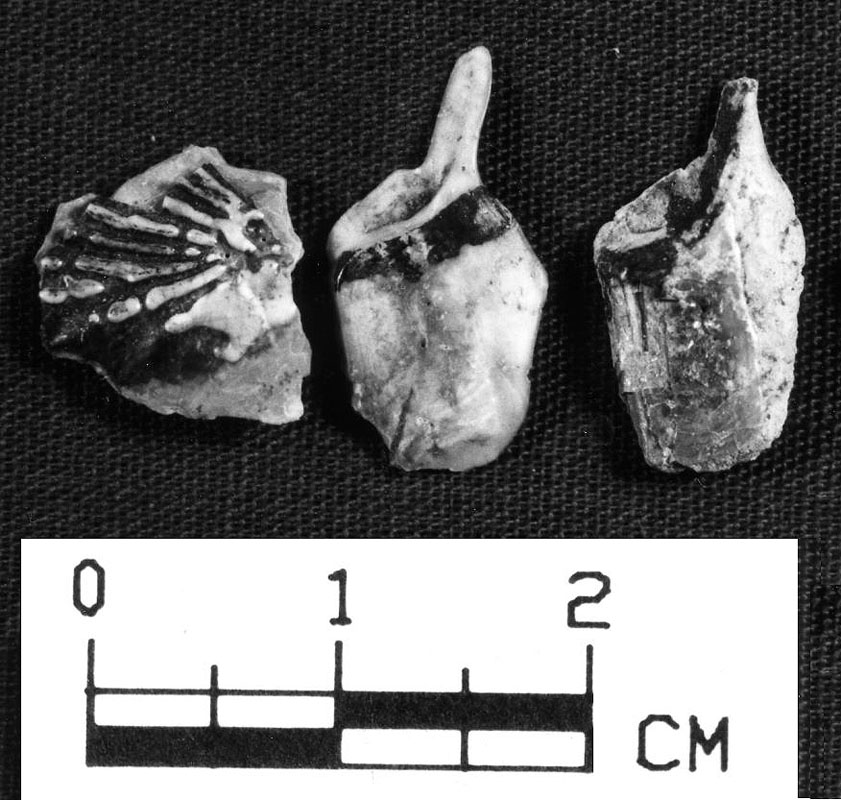

Gar was a common item on the dinner menu at sites along the coastal rivers and in the upper parts of the bays where brackish water predominates that gar can readily tolerate. Alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula), which can exceed six feet in length and weigh several hundred pounds, are heavily armored with ganoid scales—a diamond-shaped boney scale covered with a hard enamel-like substance—and have an elongated snout lined with long sharp teeth. Evidence recovered from the Kendrick's Hill Site (41JK35) and Possum Bluff (41JK24) includes 89 gar scales with residues of asphaltum, a known hafting agent. Some of the asphaltum residue was found near the distal end of the gar scale. This placement of asphaltum leads archaeologists to infer these scales were hafted to form make-shift projectile points. Another possibility is that multiple gar scales may have been set into grooved wooden shafts and used as a sickle-like tool to harvest plant resources or even as a weapon.

Several different types of musical instruments made of bone occur as grave goods at several cemetery sites along the upper coast. Examples include bird bone whistles and flutes, turtle shell rattles, and rattles made of perishable material (such as gourds) that used drum teeth as the noise-makers. Perhaps the most striking example is the incised whooping crane ulna whistles found at the Mitchell Ridge site. Similar artifacts are known only from southern Louisiana, suggesting this peculiar instrument was unique to Atakapan-speaking peoples and their ancestors. These whistles were incised with geometric designs and plugged with asphaltum in order to produce the desired tone. Interestingly, clusters of black drum teeth were found in association with one of the Mitchell Ridge graves. A reasonable explanation is that the drum teeth were part of a rattle made from a dried gourd or hollowed out piece of wood. A similar interpretation has been made for a concentration of pebbles and drum teeth found in a grave at the Harris County Boys School site on the west shore of Galveston Bay.

Many decorated bone artifacts have been recovered from cemeteries and open campsites along the upper and central coast proper, and across the coastal plain well inland. Such decorated bone artifacts range from incised bone pins typically made of deer long bone sections to incised, drilled, and/or notched bird bone beads, to name only the most common forms. These range in age from the Late Archaic to Protohistoric periods. The most elaborately decorated and unusual items are all grave goods. Bone beads, some decorated and some plain, have been found in both cemeteries and open campsites. Unusual items include shark vertebrae beads or perhaps ear plugs, carved turtle carapace gorgets or rattles, and drilled bison scapulae. Three of the latter were found with a Late Archaic burial at 41NU29, a campsite and cemetery on lower Oso Creek above Nueces Bay.

![]()

|

|

|

|