Cultures, Conflicts, and Connections

Sunset over Wink Mountain, Tom Green County. Photo by Darrell Creel. |

|

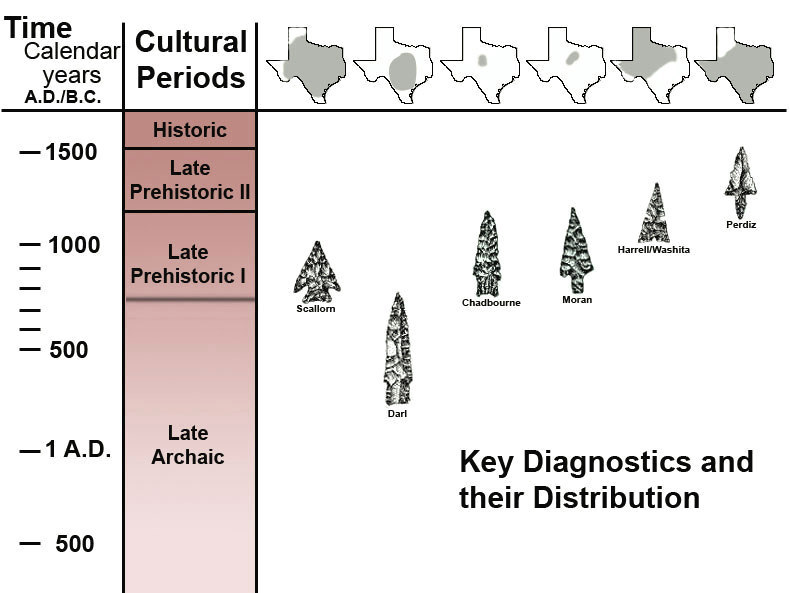

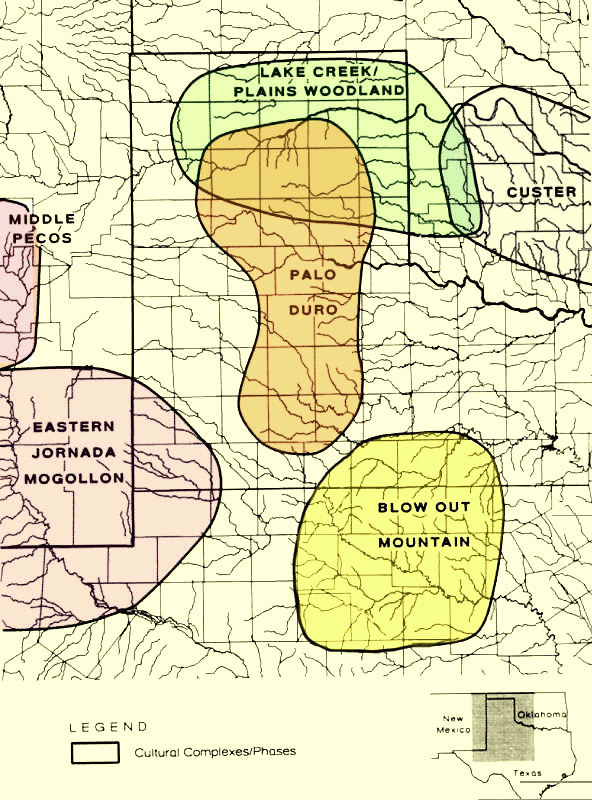

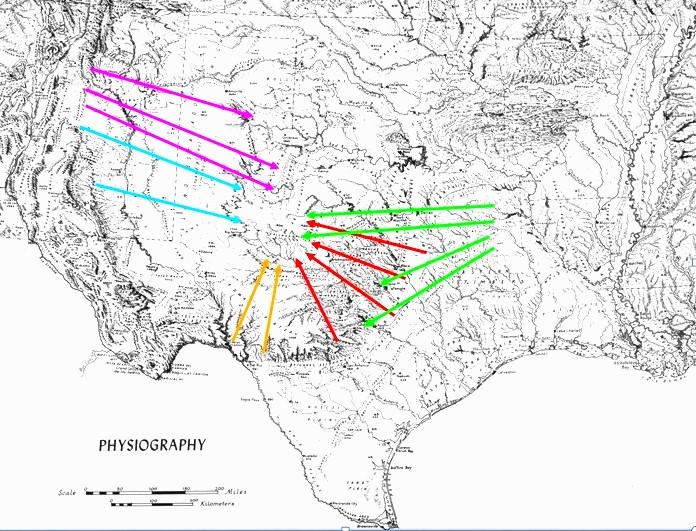

The people who built the ubiquitous cairns of west-central Texas and the culture they represent remain veiled in mystery. The little that we know about them derives largely from how they treated their dead, and the offerings and weapons found in their graves. When these scant clues are woven together along with information from other sites, we can draw a slightly more focused view of these people and the times in which they lived. Based on the presence of several types of arrow points found in a number of the burials, the cairn tradition in this region can be associated largely with the Blow Out Mountain phase, dated from roughly A.D. 800/900 to 1300, although there are some indications it may have begun earlier. Blow Out Mountain peoples were hunter-gatherers, subsisting on a diet including deer, rabbit and other small game, along with freshwater mussels, and they apparently cooked their food in slab-lined cooking features. Contact or trade with groups farther afield is signaled by the presence of burial ornaments fashioned from exotic marine shell—conch columella and Olivella—as well as a few bits of nonlocal stone found in graves. That people of this time carefully buried their dead in cairn-covered graves seems to reflect strong cultural traditions. From a larger perspective, the establishment of cemeteries suggests they were claiming specific territories in which to hunt and gather or, at minimum, designating sacred points on the landscape for mortuary purposes, places where people returned time and again to bury family and group members. More can be said about the Blow Out Mountain people by considering what was not part of their lifeway, specifically the use of pottery vessels, the hunting of bison, and the raising of crops such as maize (corn). There are no reported Blow Out Mountain sites or cairn burials containing pottery sherds or bison bone. Also lacking are Perdiz points and the distinctive end scrapers and beveled knives so common in the region during the subsequent Toyah interval, after A.D. 1300. Regional Migrations and WarfareIt is evident that the early part of the Late Prehistoric period was marked by violence, as the region's cairn cemeteries bear testament. Evidence of arrow wounds, mutilation of bodies, and the taking of war trophies is not uncommon in the burials. Who the perpetrators where, and where they came from, is an enduring mystery. What we do know is that they used the distinctive Moran and Chadbourne arrow tips, previously unknown to the area, to do their killing. The new points may signal the coming of a non-local group vying for territory and resources, or perhaps merely innovation by warlike locals. There are some indications that the aggressors may have come from, or had ties to, the east. Stylistically, the Moran type arrow point, with its parallel-sided to contracting stem, resembles points typically associated with groups in north-central and east Texas, namely Alba and Bonham types. The occurrence of similar points in west-central Texas may be related to the early Caddo intrusion into the Brazos valley and beyond, groups which archeologist Harry Shafer has termed the "prairie Caddo." It may be significant that the trait that seems to cross-cut, or distinguish, Blow Out Mountain arrow point types and some of the others is serration of blade edges and exceptionally fine workmanship on many of the points. Other intriguing hints of connections to the east come from the Crenshaw site, an early Caddo center on the west side of the Red River in Arkansas. There, archeologist Frank Schambach investigated a phenomenon diametrically opposite to the west-central Texas cairn graves—the burials of numerous skulls and mandibles with no associated skeletal remains. And unlike the cairn graves, the apparent trophy remains at the Crenshaw site had been buried in numerous pits within one plaza area. The time period of this unusual ritual activity appears to be more or less contemporaneous with the cairn burials of the Abilene area. Is it possible to relate these Red River skulls to the headless and mutilated skeletons in west-central Texas? Extensive analysis of the human remains from Crenshaw, including chemical testing, indicates that the skulls and mandibles found there are ethnically and culturally different from the resident population at that site and surrounding communities. In that analysis, no source area(s) for the trophy skulls was identified. Given that there are few, if any, other known areas with burials lacking skulls/mandibles, west-central Texas is a good candidate for the area of conflict. Whatever the nature of the prehistoric conflict that accounted for these and other deaths, it was clearly not confined to a particular region. During much of the first millennium A.D., violence was widespread across much of Texas and the southern Plains, as groups moved into other territories. Just beyond the Abilene area, warfare is evident in the burials of individuals riddled with arrow wounds. Some of these were placed in rock-lined or cairn-covered graves, apparently similar to those of west-central Texas. A large cemetery at the Harrell Site in Young County in north-central Texas contained mass burials of men, women and children whose remains bore signs of trauma and trophy taking, including removal of skulls and mandibles. A number of the burials were placed in slab-lined pits. However, Scallorn arrow points, rather than Blow Out Mountain types Moran or Chadbourne, were found in some of the graves. In a northern Panhandle site on the Red River in Donley County, two individuals were found buried in a cairn-covered grave. As reported by excavator Adolphe H. Witte in 1955, one individual was laid in sharply flexed position, head downward atop the other, who had been placed in seated position. Seven Scallorn-like arrow points—two in the first individual and five in the torso of the other—were the apparent cause of death. Several cairn burials also have been reported to the northwest in the Caprock Canyonlands and Texas Panhandle. At the Sam Wahl site in Garza County, excavated by Douglas Boyd and others, the bundled remains of a middle-aged male were found in an oval, cairn-covered pit. With the burial were a ground and striated piece of hematite and a large (ca. 6 cm-long) Scallorn arrow point with serrated blade edges, which lay on top of the disarticulated bones. In central Texas, and particularly along the Brazos Valley, dozens of burials bear signs of violence, although few, or none, of the graves were covered in stone cairns. At the Loeve-Fox site on the San Gabriel River, archeologist Elton Prewitt uncovered a cemetery harboring the remains of 25 individuals. Scallorn arrow points were found in six of the burials, in positions suggesting they were the cause of death. Conch shell pendants had been placed in some of the graves as funeral offerings. Analyses of skeletal remains from the Loeve-Fox cemetery are intriguing: the skulls were described as dolichocranic (very longheaded), as were so many of the skulls from west-central Texas cairns. These similarities, along with the findings from the Crenshaw site, underscore the need for a large-scale assessment and comparison of cemetery populations. Along the northern edge of Edwards Plateau south of the Abilene area, cairn sites also have been observed, but their function and chronology are largely unknown. Oblong and oval cairns have been reported along the canyon rims of the western plateau but most appear to have been disturbed, and none have been systematically excavated. A series of 19 rock cairns in two clusters along a creek bluff in Kendall County were documented by Harry Shafer and Thomas Hester, and three were subsequently tested. Both large and small stones filled and capped oval pits thought to have once held burials. Although no human remains were found, the absence was attributed to poor preservation. Similar cairns in a linear arrangement were recorded on a high slope in Bandera County. Although we may never know the particulars of the Late Prehistoric conflict evidenced in the west-central Texas cairn graves, we can surmise that it wreaked consierable havoc on hunter-gatherer populations. As Lawrence Keeley points out in his book, War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage, prehistoric warfare may have been small-scale by modern standards —more akin to raiding by small groups pushing territorial boundaries—but it was every bit as deadly as later warfare among "civilized societies." When hunter-gatherer conflict escalated, it could be devastating to the small societies involved. Toyah and BeyondBeginning around A.D. 1300, the Late Prehistoric II Toyah interval was a time of continued extensive interaction among groups from far-flung areas, and much of it appears to have been centered over west-central Texas. This cultural milieu is reflected most dramatically in the diverse ceramic types relating to groups in Central Texas, the Henrietta focus to the north, Frankston focus to the east, and Rio Grande pueblo peoples to the northwest. A distinctive tool kit also was carried by the Toyah folk, including Perdiz arrow points, small chipped-stone scrapers, and beveled knives. These specialized tools reflect the increased importance of bison and the burgeoning hide trade in the region. There is no agreement among archeologists about the derivation of this late, and eventually widespread, cultural expression. Several, however, have suggested that it may have developed among local groups in west-central Texas, based on similarities between Moran points and Perdiz points. Archeologist Doug Boyd has also pointed to similarities with Deadman's points of the neighboring Palo Duro complex. Based on their shape, it has been suggested that either Deadman’s and/or Moran points may be ancestral to the Perdiz arrow point, emblematic of the subsequent Toyah interval. For whatever reason, the cairn burial tradition appears to have come to an end in west-central Texas before the full emergence of the Toyah complex. In the Trans-Pecos area to the west, however, there is evidence of a later cairn burial tradition. Two remarkable cairn graves apparently related to the Cielo Complex, ca. A.D. 1400-1750, contained the remains of two individuals, both placed in shallow, rock-covered pits on high promontories. Unlike the Abilene area graves, however, these burials each contained a sizable and elaborate trove of grave offerings. At the Las Haciendas site in northeastern Chihuahua, a young man was buried under a covering of limestone chunks and two large rhyolite boulders placed in a gabled position. An offering of 194 arrow points, most of them Perdiz, a drilled malachite pendant, and a kaolinite bead, had been placed in a cluster under the head. At the Rough Run site near La Jitas, Texas, a more elaborate stone slab cairn was built to cover the partially dismembered remains of an adult male. The 300 rhyolite stones used in the cairn had been carried from a nearby outcrop and transported to the burial site. Some 60 Perdiz arrow points and a Harrell point were placed within the grave. Cairn features also are prevalent in the Lower Pecos region, although most have been disturbed. In a survey of Seminole Canyon State Park, archeologist Solveig Turpin recorded a number of circular and oblong cairns along canyon rims and in high settings with panoramic views. Many were at sites that also contained stone circles. Excavation of one cairn at site 41VV364 revealed a shallow pit covered by layers of large rock slabs and smaller stones. Although there were no bones in the pit, high phosphate levels in the soil suggested human remains had once been present. A fragmentary Perdiz point was located in the bottom of the pit, and another was recovered from screening of the burial fill, along with two dart points. Future ResearchMuch more remains to be learned about cairn burials, their derivation, and possible connections with other traditions. Critically lacking are stratified sites in west-central Texas to help us understand the Late Archaic to Late Prehistoric transition as well as the cultural upheavals of the latter times. There is considerable stylistic variation in the Moran point type and insufficient chronological information. In the same vein, a substantial modification of the Blow Out Mountain concept may be warranted. As presently understood, it may encompass too much chronological and cultural variation to be considered a single cultural period. The possibility of gathering additional archeological data from systematic excavation of a cairn site, however, is not great. It appears that most of the cairn burials of west-central Texas already have been disturbed, if not destroyed, by artifact collectors. This careless activity has resulted in a tremendous loss of information. While some collectors take the time to document what they find, most dig up graves only looking for potential grave offerings, with little regard to any human remains they may encounter. Today, archeologists rarely excavate burials except in circumstances required by federal and state cultural resource laws or as necessitated by emergency salvage. When they encounter graves during cultural resource management projects, such as survey for reservoir construction and transmission lines, they routinely consult with the Texas Historical Commission. As a rule, most professional archeologists in Texas hold the view that human graves should be protected by law and left untouched except when unavoidable or with particularly good cause, such as a significant research question that can only be answered by studying graves. Determining who the mysterious cairn people were—and what became of them— may be just such an issue.

|

|