The past century has witnessed many excavations

at Antelope Creek sites and a much smaller number of substantial

published results. Archeologists now have a fairly good grasp of

the "material signature" of Antelope Creek culture—the characteristic

architectural patterns, artifacts, and ecofacts (animal bones and

such). And we have begun to understand the geographic extent and

variation of Antelope Creek and related Plains Village cultures

in the region. But what we know pales by comparison to what archeologists

could and, frankly, should know by now.

Consider, for example, that as of 2004 fewer than

a half a dozen published reports have described, counted, illustrated,

measured, and identified source material for the stone tools and

pottery fragments recovered from a specific excavation at an Antelope

Creek site. Such technical details may seem mundane and even boring

to the general reader, but they are the critical building blocks

upon which any archeological scholar must depend. Good science demands

good data, good published data.

Improved understandings of the Plains villagers

of the Texas Panhandle will require a lot more of what is known

in other fields as "basic research." We do not

mean simply "more digging," we mean a lot more top-notch

research, in the field and the laboratory. Research carried out

by thoughtful design and research that is carried through to proper

completion including full reporting of all the technical details.

A Dozen Antelope Creek Research Problems

While dozens and dozens of basic

research needs, large and small, could and should be spelled out

and pursued, listed below are a dozen worthy research problems and

needs as identified by archeologists Chris Lintz, Doug Boyd, and

Scott Brosowske. The first four items are very basic research needs

upon which almost all interpretations of Antelope Creek culture

rely.

(1) Dating. We still need many more radiocarbon

dates from Antelope Creek sites to refine our understanding of the

origins, development, and demise of Plains Village life in the Texas

Panhandle. Lintz and others have put forth some intriguing arguments,

but most of these cannot be properly evaluated without more rigorous

sets of dates from a variety of sites, contexts, and settings.

While radiocarbon is the most widely accepted and

commonly used dating method, other useful techniques have been around

for awhile (such as archeomagnetic dating, thermoluminescence, and

obsidian hydration dating), and there are some new promising techniques

on the horizon. For instance, optically stimulated luminescence

measures the elapsed time that the quartz particles within buried

sand deposits were last exposed to sunlight and the technique could

be a particularly important tool in future archeological studies

in the region.

(2) Paleoenvironment. The past climatic history

of the Texas Panhandle before, during, and after the Plains Village

era remains imprecisely understood. While much has been made of

the apparent onset of drought conditions around A.D. 1250 and the

increasingly inhospitable conditions for the next 150-200 years,

our interpretations are based largely on extrapolations of climatic

data from neighboring regions. We need better paleoclimatic data

from the heartland of Antelope Creek culture.

(3) Economy. We still have a very inadequate

understanding of how Antelope Creek people supported themselves.

Until recently, domesticated crops (including corn, beans, and squash)

were generally assumed to have supplied most of the food upon which

Antelope Creek people depended. This assumption seems at odds with

the argument that the region experienced worsening drought conditions

during Antelope Creek days. Studies of animal bones indicate that

a wide range of species large and small were hunted, trapped, bopped,

and netted. Even so, at some sites almost 90% of the bone was broken

and reduced into unidentifiable fragments. This pattern is consistent

with the systematic extraction of bone grease and marrow, a practice

suggesting that every bit of food value was being removed from the

animal bones. Recent technological studies of ground stone manos

as well as isotopic chemical studies of human bones suggest that

horticulture (early agriculture) may have played a relatively minor

role in food acquisition.

The idea that Antelope Creek people may have been

mainly gatherers and hunters who supplemented their diets with planted

crops does not seem consistent with the considerable evidence that

they were semi-sedentary (living in one place) for much of the year.

This suggests that Antelope Creek culture would make a most interesting

case study in Late Prehistoric survival strategies, but this will

require many more well-dated samples of plant and animal remains

from a variety of sites. The use of typical ¼-inch mesh sifting

screens, while a standard recovery practice in archeology, rarely

yields the tiny, but highly informative, pieces of charred plants

and small animal bones. It is imperative that all future excavations

take sediment samples and process them using the flotation technique

to increase the recovery of this important evidence.

(4) Tool Function. Detailed studies of the manufacturing, use, and

life cycles of the stone and bone tools used by Antelope Creek villagers

are needed. Even though archeologists routinely speculate about

the function of such tools based on their general form, detailed

studies elsewhere in the world suggest that the actual functional

uses of such tools are more complicated and meaningful. The same

is doubtlessly true for Antelope Creek. For instance, Marie Huhnke's

recent study of buffalo scapula (shoulder blade) implements from

Alibates 28 suggests that most were not suited to be used as agricultural

hoe blades, as previously assumed. Instead she postulates that scapula

tools probably served mainly as trowels for mixing and applying

mortar and plaster during house construction and maintenance. Many

such thoughtful analyses are needed to give us behavioural insights

into Antelope Creek life.

(5) Architectural Patterns. Settlements in the eastern Texas Panhandle,

particularly east and south of the Canadian River, seem to have

houses that lack stone foundations in favor of picket-post walls,

but yet they have the central channels, central hearths, "altars,"

and other floor features found in classic Antelope Creek houses.

What accounts for these architectural differences? Are they merely

reflections of local conditions and available building materials

or are they indications of distinct cultural groups, such as the

one apparently represented by the Zimms complex of western Oklahoma?

We generally know very little about what the superstructural

(above-ground) portions of the classic Antelope Creek houses looked

like. Some researchers, for example, feel these houses were more

like Plains earthlodges than Southwestern-style pithouses. Accurate

reconstructions of what prehistoric houses were really like must

be based on many lines of evidence, such as thoughtful analysis

of very detailed excavation data, special emphasis on understanding

post-depositional processes (what happens to a prehistoric house

once it is abandoned and buried), and even experimental archeology

aimed at replicating such houses.

(6) Settlement Zones. Antelope Creek settlements do not occur uniformly

across the region. For instance, in the vicinity of Palo Duro Reservoir,

west of the Buried City area and between the Canadian and North

Canadian rivers, there are very few typical Antelope Creek stone

slab houses. Was this a "no-man's land," a buffer zone

between major settlement zones, or simply a place were houses were

built with picket-post walls rather than with rock foundations?

More generally, how do we explain the distinct geographic clusters

of Antelope Creek sites?

(7) Field Huts or Guest Houses? The 1962 excavations

at the Conner site and several others in the Lake Meredith area

exposed small circular structures that were associated with relatively

few artifacts and a disproportionately high number of buffalo limb

elements (leg and foot bones) from only one side of the animal.

This pattern prompted Lathel Duffield to postulate that these may

have been seasonal field huts where villagers stayed while away

from their main homesteads and hamlets. (The bone pattern suggested

organized food sharing whereby family groups may have divided up

carcasses into equal portions.) Yet, recent studies of similar,

small circular structures at the Roper and Chicken Creek sites reveal

very robust assemblages of artifacts and bones rivaling those found

at any hamlet (i.e., a typical Antelope Creek “village”).

Are these smallish sites with circular structures

really clusters of seasonally occupied field huts or could they

be areas where visiting Plains Village groups stayed while they

traded for Alibates flint? In this model, the large, typical Antelope

Creek houses were home to the resident villagers who controlled

access to the flint quarries, while visitors lived in modest, temporary

quarters. Other possibilities exist, a fact that underscores the

need for more detailed analyses of Antelope Creek structures and

their associated debris.

(8) Landergin Mesa Refuge? Lintz estimates that there may have been

as many as 95 isolated homestead-type structures built within the

half-acre top of Landergin Mesa and that these houses were built

over the duration of the Antelope Creek phase. This finding contradicts

his earlier notion that during early Antelope Creek days (which

he called the “subhomestead period”), houses were clustered

into room blocks, especially in a locality that has obvious, severe

spatial limitations. Why does the settlement pattern atop mesa sites

differ from the pattern identified around the Alibates quarries

(i.e., at Antelope Creek 22 and Alibates 28)? Was Landergin Mesa

used as a temporary refuge that was occupied for such brief periods

that contiguous structures (pueblo-like room blocks) never evolved?

(9) Antelope Creek Rock Art. Systematic archeological surveys (uniform,

thorough coverage of sizable areas) have taken place in the Antelope

Creek region only very recently (since the late 1990s). As a result,

some new site density and distribution patterns are being seen.

For instance, studies of the burned-off areas at the Alibates National

Flint Quarries have found numerous examples of rock art in apparent

association with Antelope Creek habitation sites. The rock art in

question presumably consists mainly of boulders with petroglyphs

(pecked designs) or “cupules" (cup-shaped pecked areas).

Better known petroglyph designs thought to be associated with Antelope

Creek culture include footprints and turtles. Some have also argued

that certain pictographs (painted designs) were created by Antelope

Creek artists, but pictographs are rare in the Texas Panhandle.

We are a long way from understanding which designs (if any) were

actually executed by Antelope Creek peoples. Thorough documentation,

dating, and analysis of such rock art sites might reveal common

design patterns that tell us something about Antelope Creek symbolic

and ritual life.

(10) Agricultural Technology. What particular methods were used

to grow corn, beans, and squash? Where, specifically, were most

of the agricultural fields situated relative to Antelope Creek villages?

Did they plant fields in the middle of the floodplains and hope

the floods would spare the crops? Or were the main fields on top

of the first major terraces above the floodplains? Where appropriate,

were crops planted adjacent to sand dunes to take advantage of the

water that drains from the base of saturated dunes? Or perhaps fields

were planted below steep slopes in places where run-off water could

be diverted to specific fields? While it is almost certainly the

case that various planting strategies were employed, the ancient

agricultural technology of the region has received precious little

careful study.

(11) Plains Villager Interactions.The distinct marine shell and

turquoise jewelry, obsidian, and painted ceramic vessels made by,

or at least obtained from, Southwestern groups are relatively easy

to recognize as non-indigenous (foreign) trade goods in Antelope

Creek sites. It is much more difficult to discern the trade items

obtained from other Plains Village groups in the Southern and Central

Plains, groups who made similar kinds of pottery and used similar

kinds of stone resources. Difficult, but not impossible. Detailed

studies are needed of the pottery paste characteristics and raw

material sources (based on trace elements) of sizable samples of

cordmarked pottery before we can really understand the nature of

Plains Village interactions.

(12) Cultural Identity and Conflict. Who were

the Antelope Creek peoples, who were they most closely related to,

and who were their enemies? In a recent summary of Antelope Creek

culture, Oklahoma state archeologist Robert Brooks wrote that, “Much

of the Antelope Creek mystique is linked to the biological characteristics

of the population. While study of this area is clouded by the propriety

of examining human remains, for tribes as well as archeologists,

systematic evaluation of the biological nature of these groups is

critical to our understanding of the origin and ultimate destination

of the group and its culture.” Many questions about the ethnic

identities of Antelope Creek and other Plains Village peoples can

be addressed using modern scientific techniques such as DNA studies

and craniometric (skull measurement) data analysis. Furthermore,

other innovative techniques such as a bone chemistry study called

isotope analysis can provide direct evidence on human diet that

can be used to define a group’s economy and cultural identity.

The trophy skulls at the Footprint site and the finding of numerous

burials with evidence of violence (such as embedded arrow points)

in the Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma demonstrate that considerable

hostility took place in Antelope Creek times. But who was fighting

whom? Were Antelope Creek villagers fighting each other? Or was

it raids by competing villagers from elsewhere in the Southern Plains?

Perhaps, late in Antelope Creek times, it was mainly non-villager

Athabascan-speaking intruders (ancestors of the Apache peoples)

from the northwest. Was the violence simply an inevitable consequence

of unstable “trade and raid” relationships with Puebloan

peoples of the Southwest? It seems quite likely that conflicts occurred

between and among various groups in the region for various reasons,

but we are a long way from understanding even the broad outlines

of what happened.

Although it is not always a pleasant topic of discussion,

prehistoric warfare may have had a huge impact on the lives of various

prehistoric groups in and around the Southern Plains. In his book

Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest, Steven LeBlanc

put it succinctly when he said of warfare: "It cannot be ignored

or relegated to a footnote, if the past is to be understood."

Preserving the Past for the Future

Antelope Creek architectural remains tend to

stick up like an unnaturally square thumb on the landscape of the

Texas Panhandle. As a result, most sites in the Canadian River Valley

have been vandalized, some much worse than others. For every Antelope

Creek house that archeologists have excavated, 10 or 20 others have

been dug into or completely destroyed by others. Explorers,

treasure hunters, pothunters, and curiousity seekers have all dug

up Antelope Creek houses and most were disappointed by what they

found. The combined forces of progress, housing development, and

commerce have also taken their inevitable toll and torn asunder

many ancient settlement areas.

Even so, many traces of Antelope Creek life yet remain;

if not untouched, they are at least recognizable and capable of

yielding telltale scientific clues about the human past. But today's

archeologists can only do so much. Even if we had unlimited time

and funding, we know that the archeologists of the future will have

analytical tools and research goals we never dreamed of. By modern

standards, most of Floyd Studer's archeological field techniques

were crude and not very scientifically productive, and we can be

sure that archeologists 50 years from now will look back at us with

equal disappointment. From the archeological perspective, that is

why preserving/conserving ancient sites and ancient landscapes by

leaving them intact and undisturbed is a worthy and ethical goal.

There is another, more important consideration. If

those of us living in the early 21st century don't make concerted

efforts to preserve important archeological sites, future generations

may not consider us too kindly. Every generation of Panhandle residents

looks across the landscape, flatlands and breaks alike, with wonder.

How did those who came before us survive and even thrive

for so many generations? The story of the Antelope Creek

culture isn't entirely lost and we owe it to our great grandchildren

to learn what we can about our human ancestors and predecessors

and to do that we must preserve meaningful traces of past for the

future.

|

The Canadian River Valley in the eastern

Texas Panhandle was apparently settled sparsely by Plains

Villagers compared to the core Antelope Creek area to the

west farther upstream. This impression may not be entirely

accurate as the area has seen few systematic archeological

surveys. Photo taken in Roberts County by Steve Black.

Click images to enlarge

|

A pithouse excavated at the Jack Allen

site in 1969-70 had picket-post walls and lacked the stone-slab

wall foundations found in most Antelope Creek houses. Picket-post

walls are more common in the eastern Texas Panhandle and in

western Oklahoma but it is not yet known whether they reflect

a construction technique preferred by non-Antelope Creek peoples

or perhaps a relatively early stage in the evolution of building

techniques in the region. Sorting out the meaning of such

patterns will require a larger sample of well-dated and carefully

described houses. Photo courtesy Chris Lintz. |

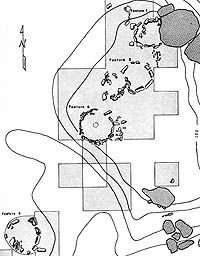

Plan map of the Roper site showing four

small circular structures that could represent seasonal field

huts or some other kind of temporary houses. From Duffield

1970. |

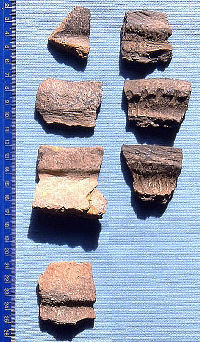

The finding of a few pottery sherds with

"collared" (thickened) rims at several Antelope

Creek sites was interpreted by Jack Hughes as possible evidence

of trade and interaction with Plains Villagers from the Central

Plains. This photo compares the four known collared rim sherds

from Antelope Creek sites with three Nebraska phase sherds

from the Central Plains. While the rims look somewhat similar,

technical studies of the paste suggest the Antelope Creek

collared-rim pottery was made locally. (On the left, the bottom

sherd is from the Cottonwood Creek site, while the other three

are from the Roper site.) Photo by Chris Lintz. |

This well-known petroglyph (pecked design)

at Alibates Ruin 28 depicts a turtle. Recent surveys suggest

that petroglyphs may be commonly associated with Antelope

Creek ruins. Thorough documentation, dating, and analysis

of such rock art sites might reveal common design patterns

that tell us something about the symbolic and ritual life

of Antelope Creek villagers. Photo by Steve Black. |

Squash growing in an experimental garden

in the American Southwest. It is not known whether Antelope

Creek people grew much squash or, if they did, where their

squash fields were situated. Much remains to be learned about

the Antelope Creek economy. Photo by Steve Black. |

These "guitar pick" scrapers

(unifaces) from the Roper site are a common occurrence on

some Antelope Creek sites. (The name comes from their suggestive

shape.) Although it is assumed they were used as hide scrapers,

there are other uniface forms present and the guitar pick

scrapers may have had a specialized function. Photo by Chris

Lintz. |

|

Much of the Antelope Creek

mystique is linked to the biological characteristics of the

population. While study of this area is clouded by the propriety

of examining human remains, for tribes as well as archeologists,

systematic evaluation of the biological nature of these groups

is critical to our understanding of the origin and ultimate

destination of the group and its culture.

-- Brooks 2004, p. 334 |

Portions of the Canadian River Valley

in the Texas Panhandle remain remote and undeveloped. Photo

by Kris Erickson. |

|