Forrest Kirkland: His Life and Work

"In August of 1933 [Forrest and Lula Kirkland] attended a family reunion and fish fry on the Llano River a few miles below Junction, Texas. While Forrest and his father were examining arrowheads the children had picked up in a nearby field, the elder Kirkland told his son of some Indian rock paintings he had seen along a bluff above the Concho River near Paint Rock, some thirty miles east of San Angelo, when he had stopped there while on a fishing trip. ...[Forrest's] father urged him to stop and see them on his way back to Dallas."

W. W. Newcomb, 1967

And so began a 10 year study of the rock art of Texas Indians by Forrest and Lula Kirkland.

Forrest Kirkland's day job was running his own commercial art studio in Dallas. The art firm created catalog images for industrial companies. His air brushed drawings for machine catalogs were considered some of the best.

Beginning with his first family, Kirkland traveled on vacations to paint landscapes in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and New Mexico. Many days on his walk to and from work, Kirkland stopped to quickly sketch Dallas scenes.

In the late 1920s, Forrest developed an interest in geology and paleontology. Pursuing the interest led to weekend excursions and then camping trips. Forrest even discovered a new genus and species of jellyfish (Kirklandia texana Caster). Kirkland helped found the Dallas Fossil and Mineral Club, but soon turned to archeology as his main interest and helped organize the Dallas Archeological Society.

Forrest divorced his first wife during this time and then married in 1931 to co-worker, Lula Mardis. Lula, who trained at the Art Institute of Chicago, joined Forrest in his exploration of Texas' prehistory. At a family reunion, Forrest's father encouraged them to stop in Paint Rock to view Indian pictographs. Forrest and Lula both sketched what they found at Paint Rock. Over the winter, they decided to spend the next summer's vacation copying rock art.

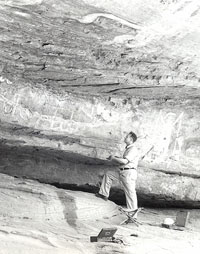

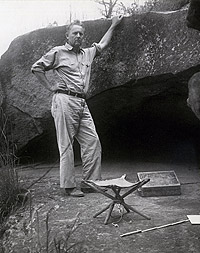

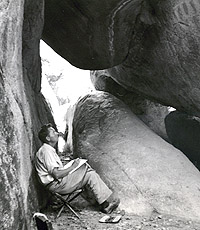

In 1934, Forrest developed his technique for copying the pictographs: careful measurement and scaling, pencil sketching, and then water coloring with matching colors. He didn't paint anything he couldn't see. His vision to preserve the rock art of Texas in watercolor became a mission. He would paint and Lula, his partner, would drive, scout, photograph, sketch, and cook. Lula performed most of the chores because Forrest's heart was weakened from childhood Rheumatic fever.

Forrest Kirkland died from a heart attack on April 2, 1942, but not before Lula and he had copied all of the known major rock art sites in Texas. The Kirklands played an integral role in preserving the trail of pictographs. Forrest planned on writing and illustrating a book on the paintings. He had progressed as far as mocking up the layout before his death.

Their hard work has been recognized by scholars and universities. Forrest's paintings were shown in several locations in the U.S. before being acquired by the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM) at the University of Texas at Austin.

One of the artist's dreams was to publish his work in a book on Texas rock art. His dream came true in 1967, when the University of Texas Press published The Rock Art of Texas Indians, featuring Kirkland’s paintings and a text by W.W. Newcomb, then director of the TMM. Kirkland created the paintings, many of the rock art images he recorded have been destroyed or damaged. When Amistad International Reservoir was completed in 1969, many Lower Pecos rock art sites disappeared beneath the waves. Other rock art sites have been damaged by vandals or by natural disasters such as major floods. And all surviving rock art, particularly pictographs, are subject to continued natural weathering. The past continues to fade. Not only do Kirkland’s paintings help document these sites, they also enable others to study them without hardships and offer inspiration to those who view them.

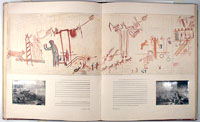

Before he died, Forrest Kirkland created a mock-up of the book that he hoped to write. Using the watercolor sketches that he made on-site, Forrest would recreate the murals from the shelters in color. At the bottom of each mural, Forrest pasted Lula's black and white photographs to give the reader a sense of the countryside.

Most of the watercolor copies of rock art that Forrest Kirkland made in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands are included in this virtual catalog. While Kirkland numbered his plates chronologically in the order he created them, W.W. Newcomb developed his own numbering system for the 1967 publication (reissued in 1996) in which the plates are geographically ordered. In this exhibit, Newcomb’s organization is followed, making it easier for viewers to compare the gallery images to those in the published book. The Plate Directory [Link]cross references the two plate numbering systems.

Kirkland, Forrest and W.W. Newcomb, Jr.

1967 The Rock Art of Texas Indians. University of Texas Press,

Austin. Reissued in 1996.