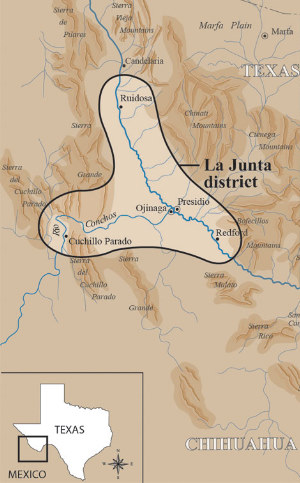

La Junta de los Rios:

Villagers of the Chihuahuan Desert Rivers

Indian couple overlooking La Junta de los Rios. In the foreground is the Río Conchos which joins the Rio Grande on the far right. Across the landscape are agricultural fields, a farming hamlet of circular houses, and, in the lower right, a pueblo (village) with flat-roofed adobe houses. The details are inspired by eyewitness descriptions in Spanish documents. This 1994 painting by artist Feather Radha can be seen in Restaurante Lobby's OK in Ojinaga, Mexico. Courtesy Elsa Socorro Arroyo. |

|

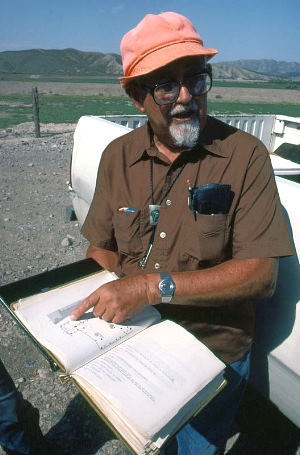

Along the southwestern frontier of Trans-Pecos Texas and northeastern Chihuahua, the two largest rivers found within the vastness of the Chihuahuan Desert join one another in a confluence of that most precious desert resource—water. The Rio Grande and Rio Conchos meet at the sister cities of Presidio, Texas and Ojinaga, Chihuahua within the Presidio Bolson, a drainage basin framed by serrated mountain ranges. Here beginning around 800 years ago (A.D. 1200), if not earlier, village life was established at the river juncture the Spanish named La Junta de los Rios. These settlements were partially supported by agriculture and trade, although wild animals and plants were integral to the La Juntan diet and way of life. The transition from nomadic hunting and gathering lifeways to sedentary village life appears to have still been underway when the Spanish arrived with Old World crops and livestock in the 16th and 17th centuries. Based on the early written accounts and emerging archeological data, La Junta was a cultural crossroads where farmers and hunters, nomads and villagers, peaceful and aggressive native groups came and went, mingled and traded, celebrated and conspired. It was like no other place in the Trans-Pecos Mountains and Basins. The native villages at La Junta were first seen by Europeans in 1535 when Cabeza de Vaca and three companions traveled through the area. Beginning about 45 years later, a number of Spanish entradas (expeditions) passed through La Junta, providing written accounts of the native peoples living in scattered villages along the two rivers. These expeditions set the stage for a greater Spanish presence in the area, culminating with the establishment of missions in the 1680s and presidios (forts) in the 1760s. Later, in the 1800s, La Junta was a stopping point on the Chihuahua Trail, a trade route that linked the port of Indianola, Texas on the Gulf of Mexico and Chihuahua City, Chihuahua in northern Mexico. In the early 1900s the area was briefly renown because of its ringside seat on the Mexican Revolution. Today La Junta is part of a unique border culture that is largely isolated from the outside world, a remote spot on the sparsely settled borderlands amid the Chihuahuan Desert. The Spanish accounts of La Junta have been interpreted and debated by Southwestern historians and ethnohistorians for many decades. Yet much of the story of its native peoples remains to be fully told, particularly that of its earliest human history in prehistoric times. The Spanish were drawn to La Junta because of what it already was—an established cultural crossroads. La Junta was, in fact, what can properly be called the southeasternmost outpost of the ancient American Southwest. Here the Spanish found settled peoples living in flat-roofed houses and growing crops, people who knew of peoples and places hundreds of miles away. But how did this cultural crossroads come to be in the first place? When did settled life begin at La Junta? Who were the first villagers? Were they Jornada Mogollon colonists or were they indigenous peoples from the local area who adopted the Southwestern lifestyle? To what extent was early village life a full-time existence based on agriculture? How were the La Juntan villagers related to contemporary hunting and gathering groups? Did La Junta supply resources to the great redistribution center of Casas Grandes in northwestern Chihuahua? Did La Junta experience a prolonged period of abandonment before the Spanish arrived? How did La Junta life change through time? This exhibit addresses these questions and tells the story of La Junta's native history based on archeological evidence and ethnohistorical interpretations of Spanish documents. We also tell the unfinished story of archeological investigation. These stories are still unfolding—a great deal of research remains to be done. Yet we know enough to realize that La Junta deserves to be recognized as a far more significant place in the human history of the southeastern American Southwest and the Trans-Pecos Mountains and Basins than most of us know. The archeological investigation of the La Junta got off to a very good start in the 1930s and 1940s with the pioneering work of J. Charles Kelley, who grew up in nearby Balmorhea. Kelley was introduced to archeology in the early 1930s as a student of Victor J. Smith, who taught industrial arts at Sul Ross State College and became the first resident archeologist of the Big Bend. Beginning in the late 1930s, Kelley literally put the La Junta '"district" on the archeological map and brought it to scholarly attention. His 1947 dissertation at Harvard University combined his archeological findings with ethnohistoric research on Spanish accounts of La Junta. But in 1950 he moved to Southern Illinois University where for the next 26 years he was a professor of anthropology and a museum director. He soon shifted his primary research interests southward into the northern frontier of Mesoamerica. There he spent many seasons carrying out fieldwork in north-central Mexico, particularly in the Mexican states of Durango and Zacatecas while investigating the Chalchihuites culture. Almost 40 years would elapse before anyone would follow in his La Juntan footsteps. Thus, until recently Kelley's ideas have been almost all we've had to go on. He himself knew full well that his interpretations were tentative and often based on meager data and incomplete analyses. Kelley returned to his Trans-Pecos roots when he retired in 1976 and moved to Ft. Davis. He was most gratified to see new research get underway in the La Junta area in the 1980s under Robert J. Mallouf, then the State Archeologist of Texas. Before he died in 1997, Kelley published several studies summarizing his earlier work and putting forth his latest thinking. It is no exaggeration to proclaim that most of what we now know about the native history of La Junta de los Rios can still be credited to J. Charles Kelley. In the last two decades modern research methods have been brought to bear on the archeology of La Junta, albeit on a relatively small scale. State-of-the-art archeological research is time-consuming and quite costly. While much remains to be done and many questions are yet unanswered, ongoing archeological field investigations, new laboratory analyses, and renewed ethnohistorical research are yielding new insights. So have the results of concerted research in adjacent regions, especially the greater American Southwest. In This ExhibitThis exhibit forms a lengthy narrative telling the story of La Junta and its peoples through time, and of the archeological research upon which it is based. Follow the La Junta story or visit sections of interest. In the first section, explore the Natural Setting of La Junta and its immediate surroundings. Those who have lived here have always been drawn by the water and attendant resources of the three-pronged oasis amid the surrounding desert mountains and basins. Chronology sets forth the La Junta area's culture history framework as categorized by archeologists, beginning as early as 2,000 to 3,000 years ago in the Late Archaic period and continuing through the Bravo Valley cultures to modern times. Investigations sketches the history of archeological research at La Junta from the 1930s through to today. Sites takes at the closer look at each of the localities in the La Junta district where archeological excavations have taken place. First Villagers is the first of four sections summarizing what we know about the human history of La Junta. Village life began about 1200 years ago with the outset of the La Junta archeological phase. Early Encounters 1535-1714 La Junta's written history begins with the arrival of the Old World Spanish intruders bent on colonizing the New World and subjugating the native peoples of the Chihuahuan Desert. Spanish Frontier 1715-1821 sees the Spanish try and fail repeatedly to establish a frontier outpost at La Junta. This period saw the demise of most of the native societies that had called La Junta home. Mexican Border after 1821 summarizes the relatively rapid cultural changes that occurred at La Junta and throughout the entire region during the 19th and early 20th centuries. New Insights on La Junta's early native peoples is emerging from ongoing archeological research, especially special studies of pottery and of human interments. La Junta Reconsidered evaluates what archeologists have learned about prehistoric and early historic life in the district and outlines what remains to be learned. Credits & Sources acknowledges those who created this exhibit and provides references to printed and Internet sources for more information. Also provided are many published articles about La Junta that can be downloaded as PDF files. |

|