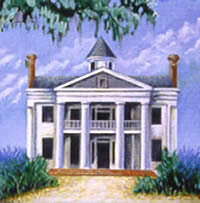

The main house was a stately mansion

with six galleries and towering pillars. Built of brick

covered with stucco, the house had the appearance of

solid stone construction. Painting by John R. Lowery,

courtesy Lake Jackson Historical Association.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

Massive debt and murderous family rancor ravaged

the Jackson business, and the plantation eventually

had to be sold.

|

Excavation at the Jackson Plantation

sugar mill is helping archeologists understand changes

in construction and refinery technology over time, as

slave labor was supplanted by convict labor. Photo by

Norman Flaigg.

|

Descendants of John Jackson, oldest

son of Abner and Margaret Jackson, tour the ruins open

house held during the Texas Archeological Society of

field school. Some 300 strong, the "Black Jacksons,"

as they refer to themselves, hold a family reunion each

year in Brazoria County.

|

|

On the lush banks of a tranquil lake on the

upper Texas Gulf coast, the crumbled ruins of brick buildings

are all that remain of a once thriving plantation. The business

of the plantation was making sugar: thousands of pounds of

sugar cane grown in the fields were processed in the plantation's

mill. First African-American slaves, then convicts from nearby

prison farms provided the backbreaking labor to make the industry

profitable in the fertile coastal land known as the "sugar

bowl of Texas."

Built by Abner Jackson and his wife, Margaret,

in 1844, the Lake Jackson Plantation became one of the most

profitable sugar refineries in the state. Over time, Jackson

expanded his namesake property to almost 3750 acres and acquired

two additional plantations, Darrington and Retrieve. But massive

debt and murderous family rancor ravaged the Jackson business,

and Lake Jackson plantation eventually had to be sold. Subsequent

owners struggled with the upheaval in business brought about

by the Civil War, a changing economy and a new labor force.

In 1900, the infamous hurricane that killed over 6,000 people

in Galveston also delivered the final death blow to the plantation,

nearly leveling many of the stately buildings and sugar mill

complex. Although the land continued to be cultivated for

crops and later was used as range land for cattle, the buildings

were never reconstructed.

Nearly a century later, archeologists began

probing the weed-infested ruins, hoping to learn more about

the plantation and the technology of sugar making. Joan Few,

professor at the University of Houston at Clear Lake, has

directed excavations at the site near Freeport, Texas, since

1992. Now a State Archeological Landmark, the property includes

the remains of 12 structures on roughly four acres of land—a

mere shadow of the original plantation.

Through the efforts of hundreds of volunteers

and students, including members of the Texas Archeological

Society (TAS) and the Brazosport and Houston archeological

societies, much of the elaborate brick-walled plantation and

mill complex has been uncovered, allowing researchers to track

changes in construction through time. Significantly, archeologists

learned to recognize the finer craftsmanship of the slave-labor

era, as distinguished from the poorer quality work produced

by convicts.

Today there are no nineteenth-century sugar

mills standing in Texas, but archeological research at Lake

Jackson has provided a wealth of information on the first

industry in Texas, that of refining sugar.

Missing from the archeological record, however, are

the stories of the black slaves who provided the sweat and

labor to create the Jackson empire. Because the slave quarters

were located on the other side of the lake, they were not

explored during archeological excavations. For this reason, this exhibit does not delve into the histories of the "Black Jacksons." These families—the descendants of John Jackson, oldest son of Abner and Margaret Jackso—gather at the plantation each June and maintain their family histories. In her recently published book, Sugar, Planters, Slaves, and Convicts, Few devotes several chapters to the history of the Black Jacksons based on both historical records and interviews with family members.

The following sections take a look at the Jackson plantation and the sugar-making process. A

special section highlights the summer field schools of the

Texas Archeological Society in 1994 and 1995.

|

Sugar cane growing in a field in

south Texas. Photograph courtesy of Texas Parks and

Wildlife Department.

|

Visitors tour the excavations in

progress at the plantation. Photo by Norman Flaigg.

|

|

Archeological research at sites like Lake Jackson

has provided a wealth of information on the first industry

in Texas, that of refining sugar.

|

Aerial photo of the Lake Jackson

Plantation taken in 1930, showing locations of main

house and mill. Image courtesy of Lake Jackson Historical

Association.

|

|