Native Peoples in a Spanish World

|

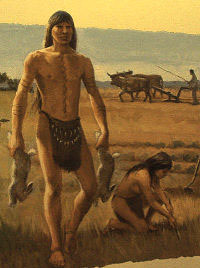

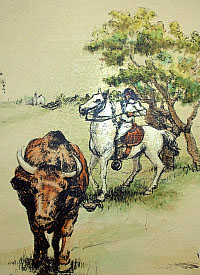

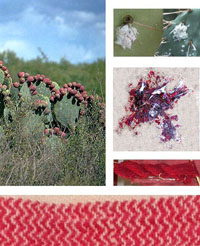

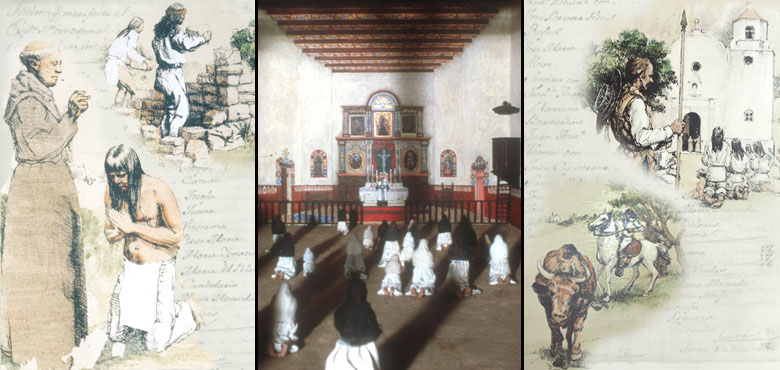

| Life in Spanish missions included instruction in religion, language, crafts, ranching, and farming. Images courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

|

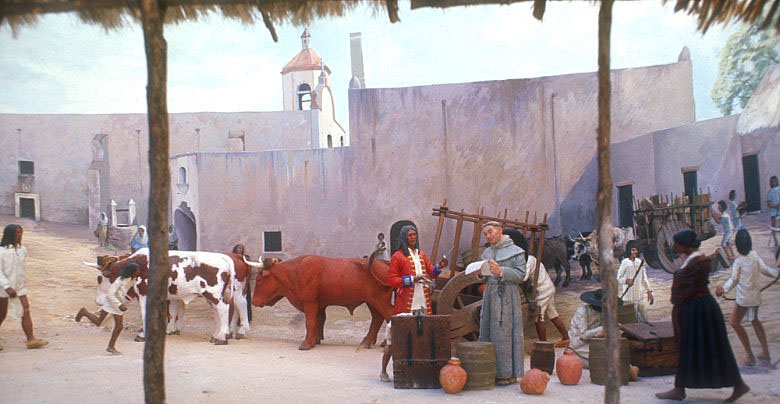

| A friar checks supplies brought in by ox carts in this bustling scene at Mission Espiritu Santo. Although the aim of missions was to become self-sufficient, staples-such as corn- were needed frequently, particularly in the years when crops failed. Diorama, Mission Espiritu Santo State Historic Site, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

|

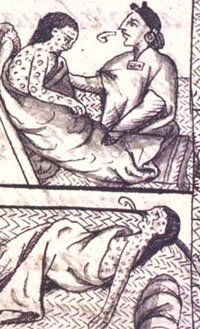

A New Way of LifeEstablishment of a mission on the frontier required the construction of living quarters, a church, workshops, granary, and irrigation system to ensure water for the crops. These facilities would help the mission in its goal of achieving self-sufficiency. Bringing this vision to life was a stepped process: as native peoples were brought into the fold, they had to be trained in a variety of new skills including digging trenches, quarrying and laying stone, making mortar using lime made in special kilns, and a host of other construction jobs. Along with these building trades, they also were taught the skills needed to grow their own food, planting crops—corn, beans, melons, squash—and raising livestock—cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. As it developed, cattle became a critical mission resource, supplying much of its food and income. Native vaqueros tended the herds, periodically rounding up a number for branding or slaughter, or to send to market. Native women were taught to spin yarn, and operate the intricate mechanical looms to weave the fabric in which mission residents were clothed. Steps were also taken to alter other manifestations of nativism—names, languages, and appearance—as well as change native worldviews. Neophytes were given regular instruction in both Spanish and Latin, as well as in Spanish culture and citizenship. By 1758, nearly 500 baptisms had been performed at the 4 th mission on the San Antonio River. In the ceremonies, some of the neophytes were given names that reflected their new skills. Perhaps the native individual identified as “Domingo Sacristan” played a role in the church, whereas “Santos Violinist” may have played a new instrument for the entertainment of those at mission dances. Such events, combining music and dancing, were intended to replace traditional native ceremonies held in the woods. Religious instruction was a regular occurrence, the neophytes summoned by the call of a bell. In a 1767 report, good progress was indicated: Frequently, even daily, the padre teaches them to pray and explains to them the Christian doctrine, the mysteries of the holy faith and such things as are necessary for salvation. …He also assists them spiritually, teaching them the commandments, urging them to be good Christians, tolerating no wicked practice, punishing all offenses and misdemeanors, and insisting that all work and observe the law. Gaspar de Solis 1767 In its most strict iteration, the mission process was intended not only to convert the Indians to Catholicism but to destroy all aspects of native culture, replacing it with the more “civilized” Spanish way of life. As described in the Gaspar de Solis report, however, the native population in 1767 apparently still held tenaciously to native trappings. Estimated at about 300, the group included “65 warriors, thirty of whom are armed with guns and the other thirty-five with bows, arrows, spears, and boomerangs" (the latter, no doubt, a reference to wooden rabbit sticks). It is not clear whether there was ambiguity on the priests’ part about discouraging traditional ways or whether the native peoples resisted. As they entered the Spanish world, native peoples brought with them a variety of useful abilities, including making chipped-stone tools and fashioning pottery from local clays as well as skills as hunters and gatherers. Drawing on thousands of years of learning in the natural environment, indigenous peoples knew which plants could be employed for various uses, when they were best gathered, and how to process them, whether for food, dye, medicines, or fiber. During periods of drought, mesquite beans, a traditional native food, were gathered to supplement the mission diet of corn and beef. The pods could be ground into meal to make into pancakes or bread. Tunas, the fruits of prickly pear cactus, could be harvested in the summer, followed by pecans and other nuts from along the river in the fall. Hunters, apparently using traditional weapons, procured a variety of wild game and fish. These traditional practices apparently were allowed to continue in spite of the friars’ aim to eliminate all aspects of native culture. Native women supplied the missions with utilitarian pottery vessels for cooking and storage, and men continued to make chipped-stone tools, including hide scrapers and arrow points used in hunting. The knappers also made chipped-stone gunflints for the Spanish guns. A few arrow points were made of material brought in by the Spanish, including metal and glass. These items, perhaps more than any other evidence, attest to steps in the acculturation process, as a few traditional ways gave way to new. Overall, the conversion process was expected to be a lengthy and complicated endeavor, and the priests understood that it could take years to effect a lasting change. As observed by Father Espinosa, " When the poor wretches come into our missions, we have to be indulgent with them for a long time in order that they may become accustomed to systematic labor." |

|

|

|

|

| Changing technologies. Native peoples used their knapping skills to produce chipped-stone gun

flints and "strike-a-lights" which, when struck with a metal object, produced a spark to ignite

gunpowder in flintlock guns or create a small flame . See more examples of chipped-stone gunflints. |

|

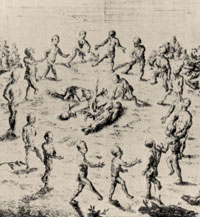

Spanish Perspectives/Native ViewsThe Spanish way of life required order, discipline, and scheduling. Such concepts were foreign and unnatural to native peoples. Although we have no written accounts describing their mission experience, we can only guess that the dualing cultures produced tension and an undercurrent of uneasiness. Accustomed to roaming freely across the land, native peoples found themselves tethered, albeit loosely, to a permanent location. Structures and walls of stone and nails eventually replaced shelters of brush and branches. Bare or scantly clad bodies were covered with long pants, skirts, and shirts woven of cotton or wool. Whereas the rising sun once signaled the beginning of their day, natives in the mission were awakened to the tolling of strange bells, songs and prayers chanted in odd-sounding tones. Beyond the physical manifestations of the conversion process was introduction to a wholly different view of nature. Breaking with age-old traditions of hunting and gathering from the wild, mission natives were taught that nature could be controlled, that land could be made to produce, and that different breeds of animals could be tended or herded and harvested as needed. Priests complained that the native peoples were lazy and undependable. Some slipped away to participate in rituals, called mitotes, which the friars found barbaric. As described by Fray Jose de Solis in a 1767 diary entry: “… when the ministers are not watching them, they go off to the woods and there hold their dances. …the men make horrible grimaces and look like demons; they are painted in bright red or black colors and with rings about their bloodshot eyes.” Some left the missions for days, even months or years at a time, to join other groups and pursue their traditional hunting and gathering way of life. The Aranama reportedly deserted the mission from 1761 to 1769, choosing to live among the Tawakoni near modern Waco. Father Garza successfully returned the neophytes to the mission fold, only to have them depart again. Much to the dismay of the friars, some clearly learned to “work the system,” moving about the land as before and adding the corn and beef of the missions to their seasonal rounds. Requiem Ultimately, the Spanish failed in their mission among the natives peoples of south Texas, the pull of ancient traditions and the power of disease and politics proving too strong for the friars to overcome. As mission cattle herds were diminished by raids and theft, the friars became desperate for supplies and food, and could not effectively sustain the effort. Mission Espiritu Santo was secularized in the early 1800s. Spanish officials determined that the few natives remaining at the time were not fit to take ownership of the mission land. Some of the former neophytes remained in the settlement of La Bahia, others moved to San Antonio or Mexico. Like countless other indigenous groups of the South Texas Plains, the Aranama and the other native inhabitants of Mission Espiritu Santo disappeared within other native groups and became culturally extinct. Reportedly, ethnologist A. S. Gatschet in the late 1800s visited a group of Tonkawa who remembered living with the Aranama. He was able to learn only two words of the Aranama language from them.

|

|