Some 40 years after the fieldwork

ended in 1968 the story of Arenosa Shelter remains half-told. A thorough scientific report on the site was to be Dave Dibble’s magnum

opus. Sadly, he never achieved this ambition—life intervened.

By

the end of the Amistad archeological salvage program time and money were short and

Dibble refused to do a hurried job on such an important site. He 1970 he became the acting director of the Texas Archeological Salvage Project at the University of Texas (which became known as the Texas Archeological Survey in 1973). For the next 15 years Dibble oversaw archeological investigations done under contract

with various governmental agencies and private businesses. Contract after

contract transpired and Dibble helped train many young archeologists. Arenosa

lingered on the back burner, and he told himself he would sit down and finish

it when things slowed down. Health problems led to early retirement

in 1984, yet he remained hopeful that he could do justice to the

site. Unfinished, Arenosa haunted him until the day he died in 1993.

Fortunately, some important chapters of the Arenosa story have been told.

Soon after the Arenosa excavations ended in 1968, analysis of the many artifacts

and geologic samples recovered from the site began. The three most extensive

studies of the site’s materials were Ph.D. dissertations completed by Michael B. Collins

in 1974, Peter C. Patton in 1977, and Christopher J. Jurgens in 2005.

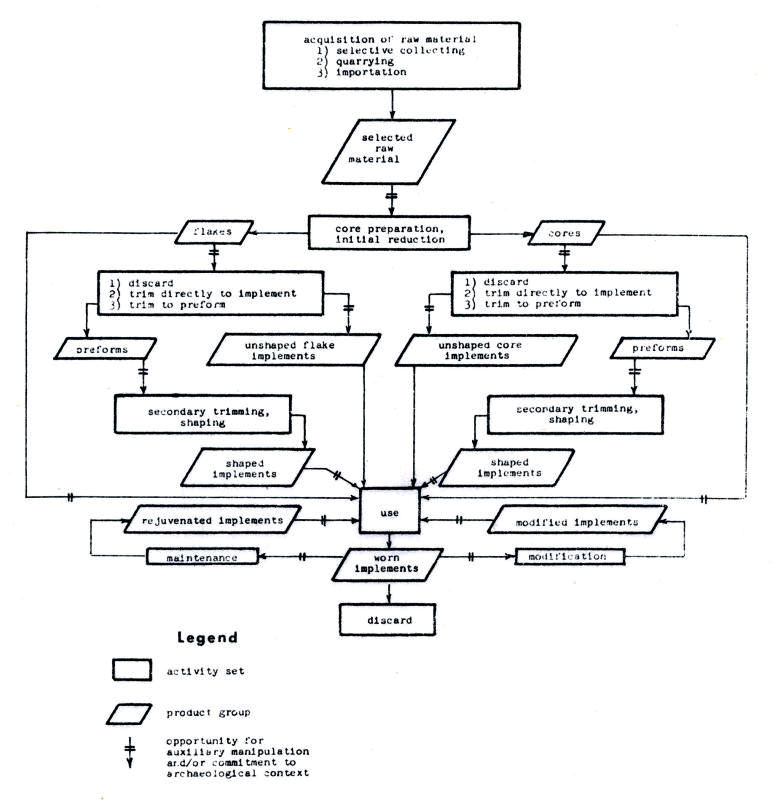

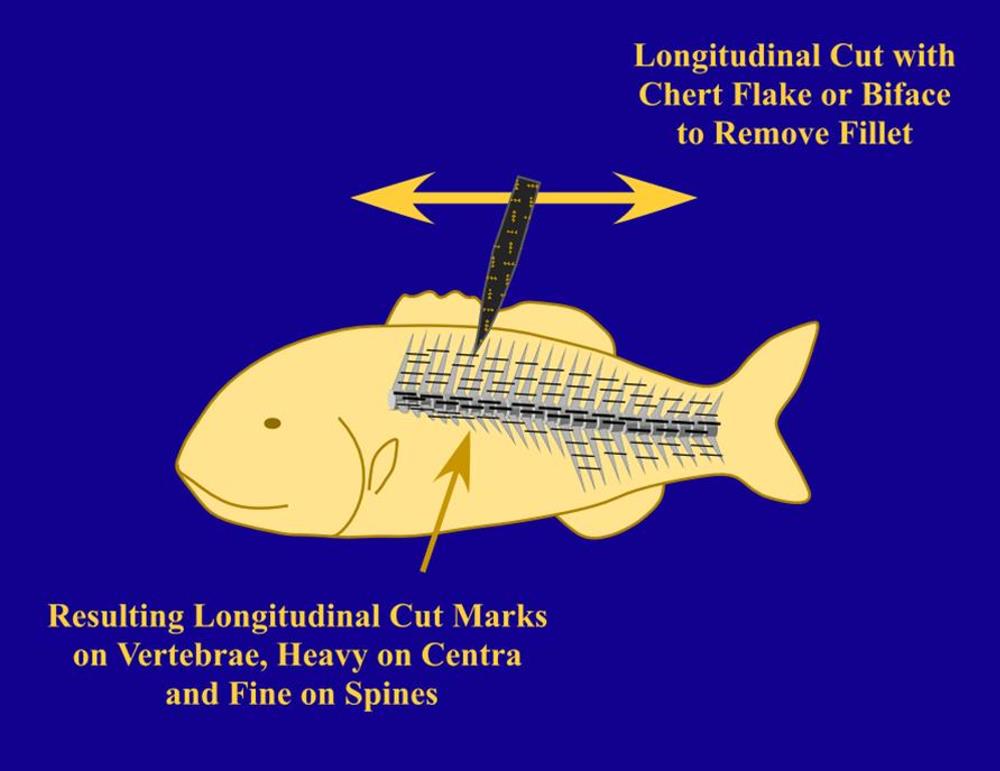

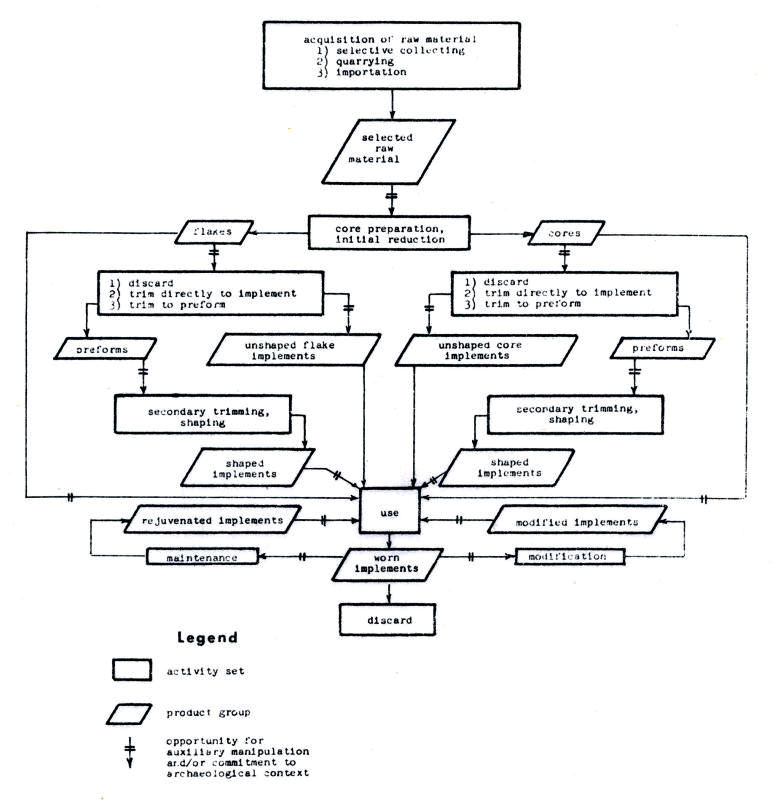

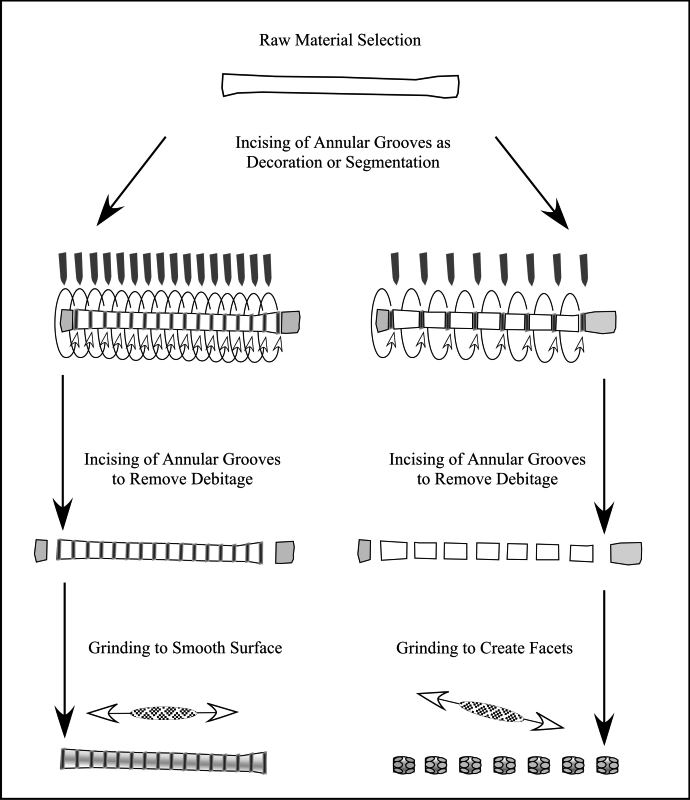

Collins studied the distributions of Arenosa’s lithic artifacts

and the debris from their manufacture to characterize patterns of chipped

stone tool manufacture at the site through time. His was the first comprehensive technological lithic analysis done in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. As Collins explained, chipped stone tool manufacture or "flintknapping"

begins with the acquisition of raw materials and passes through one or more

of the following steps: initial reduction, primary trimming, secondary trimming,

and maintenance and modification after use.

Collins found that of the three sources of chippable stone in the Arenosa

area (river gravels, upland chert outcrops, and ancient upland gravel deposits),

river cobble chert from the streambed of the nearby Pecos River was the favored

tool-making material. Smaller quantities were used of limestone, jasper, chalcedony, basalt, sandstone,

agate, petrified wood, and quartzite taken from the active and buried gravel bars of the Pecos and Rio Grande

Rivers. Chert was also gathered and flaked

in small quantities from Devils River formation outcrops and ancient gravel deposits

along the margins of the plateau.

Collins found that the early stages of stone tool manufacture were carried

out in much the same way throughout the occupation of Arenosa. Initial reduction

was accomplished by direct percussion with a relatively hard object, the hammerstone. Using softer tools such as antler, hardwood, and bone billets and flakers, percussion

and pressure flaking were then used in the primary trimming of both the flakes and of the cores produced by initial reduction. Bifaces and preforms were trimmed from

both flakes and cores, and a variety of simple tools, such as unifaces, were

fashioned from flakes by primary trimming.

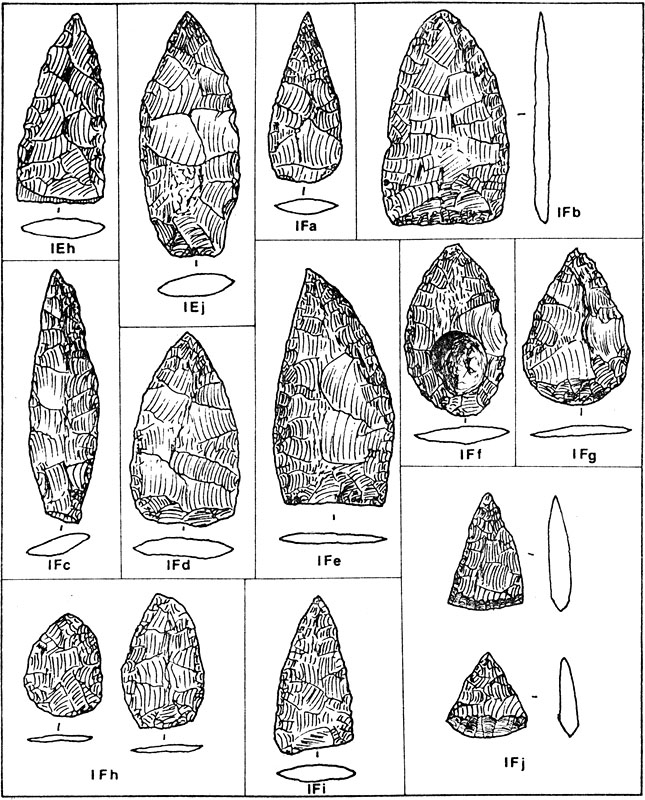

Collins found that the greatest technological contrasts through time at Arenosa

were in the amount of secondary trimming that was done and the techniques

by which it was accomplished. Soft hammer percussion was the method of choice

for secondary trimming throughout most the sequence, but was executed with

a variable amount of skill. A moderate amount of secondary trimming was done

during the earliest occupation of the site, executed with a moderate amount

of skill. Skill steadily improved through time and reached a very high level

during the latter Middle Archaic and early Late Archaic periods. The terminal

Late Archaic period brought a shift in technique to hard hammer percussion

and pressure flaking, and a dramatic decline in the skill and amount of secondary

trimming that was done. During the latest period of occupation, the Late Prehistoric period, there was

an increase in the amount of secondary trimming with a gradual return to soft

hammer percussion of moderately skilled execution.

Collins was the first researcher to systematically evaluate heat treatment, a fascinating and theretofore unappreciated aspect of the lithic reduction process evidenced at Arenosa Shelter and by extension the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. In a nutshell, the flaking characteristics of some chert artifacts (usually primary trimming flakes and core tools) were improved by slowly heating the material, thus giving it a more glass-like luster and flaking characteristics. This was especially useful in rendering particularly tough chert into more easily flaked material. Collins found that heat treating was mainly used as an "adjunct" to the production of bifaces at Arenosa throughout most of the site's history.

Patton's Arenosa work figured prominently in his geomorphological study of the frequency of flooding of greater "central Texas." He examined the soil samples and monoliths

taken from Arenosa in order to reconstruct the history of flooding at

the site. Dibble encouraged the study and helped secure additional radiocarbon dates to pin down the timing of the site formation. Patton demonstrated that Arenosa had been flooded repeatedly by both the

Pecos and Rio Grande over the last 11,000 years, including at least ten

truly massive floods between about 9000 and 1500 B.C.

At the top of his list was one of the largest historical floods ever recorded in Texas, the 1954 flood caused by Hurricane Alice. Even the most ancient rancher in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands had never seen anything like it. The Pecos River rose some 88 feet (27 meters) above its normal level and permanently changed the landscape. The massive flood ripped up huge trees, sent house-sized rocks tumbling, scoured out new river channels in some places, and left behind thick layers of sand, silt, and debris in others. Patton calculated

that the 1954 flood was at least a 2,000-year event. In other words, statistically,

a flood of its magnitude should occur no more frequently than once every 2,000

years, and possibly as seldom as once every 10,000 years.

Christopher Jurgens, comprehensive analysis of Arenosa's

fauna focused on a sample consisting of approximately 10% of the bone specimens recovered during excavation. He studied 4896 of the total of about 47,000 faunal specimens

and was able to identify over 140 vertebrate taxa and determine how Arenosa's bone tools were manuctured and used.

About 69% of the sample consisted of mammal bone, 28% of fish bone, 2% of

bird bone, and 1% of reptile bone. Rabbit was the most common animal, followed

by deer, then medium to large fish, mainly catfish, suckers,

and gar.

Among the sample were 547 of the pieces of bone were classified as artifacts, whole bones and fragments that had been used as tools or fashioned into ornaments. This sample

represents about 55% of the total bone artifact assemblage of Arenosa. Tools

and their byproducts made up 56% of the sample and beads and their byproducts

made up the remainder. Jurgens found that mammal, fish, and bird bones were

all used as raw material to make bone artifacts, but that mammal bones were used

most often (about 85% of the time). Of these, rabbit and deer provided most of the bones used to make tools. Hawk bones were commonly used to make bone beads.

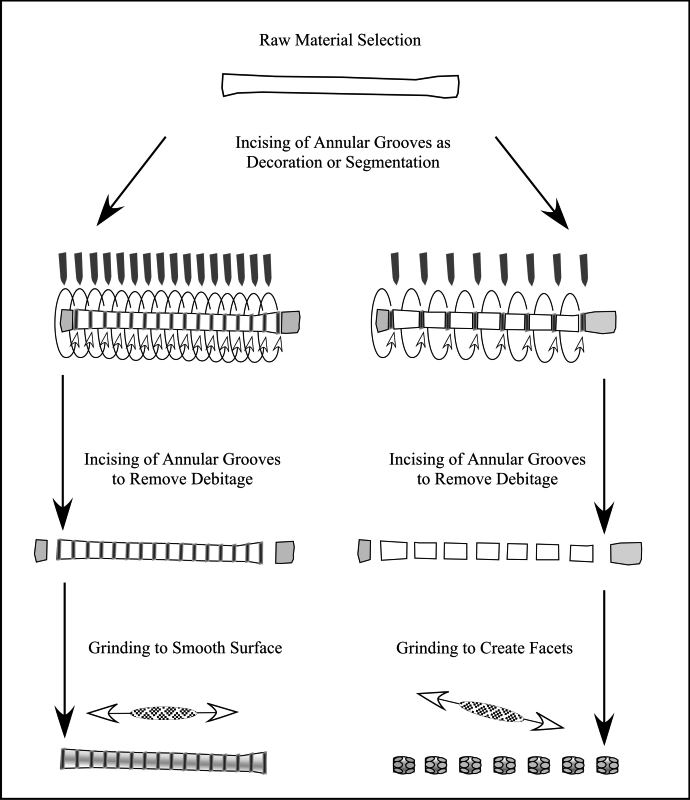

By carefully examining the bone artifacts, Jurgens was able to identify traces

left behind by the manufacturing process that revealed how they were typically made.

The first step, of course, was to select

a suitable piece of bone to work on or use. "Informal" bone tools were quickly fashioned tools typically made on bone fragments (usually butchering waste) which had been minimally modified by forming a working edge by scraping or flaking, if one was not already present.

"Formal" artifacts were more purposefully manufactured Typically, grooves were cut into the chosen bone with a

chert tool, such as a sharp flake, and the bone was snapped apart to remove a “blank.” The artifact blank

was then scraped with a chert tool to remove the bone’s outer surface and

smooth and shape it. Finally, the blank was ground to remove any unwanted

portions and sharpen the edge or tip. Occasionally, decorative patterns were added as incised lines.

By identifying microscopic and macroscopic (visible to the unaided eye) use wear characteristics ("wear patterns") on the bone beads and tools, Jurgens

was also able to determine how the bone artifacts were used. Arenosa’s bone beads were strung on plant fiber cordage and

sinew to create necklaces and bracelets. Some were also likely sewn onto plant fiber-based textiles (such as woven straps) and

leather or fur for decoration.

Bone tools were used in many different tasks. Formal bone tools were used to strip tree bark from

shrubs and small trees, strip and separate the fiber from desert succulent

leaves (such as lechuguilla), manufacture cordage and textiles (including netting) from plant fiber,

split and shape small pieces of wood, butcher meat, work dry hide and hide

with attached hair, sew plant fiber cordage or sinew, and craft lithic tools.

Informal bone tools were used to process plant fiber, butcher meat, and work

hides.

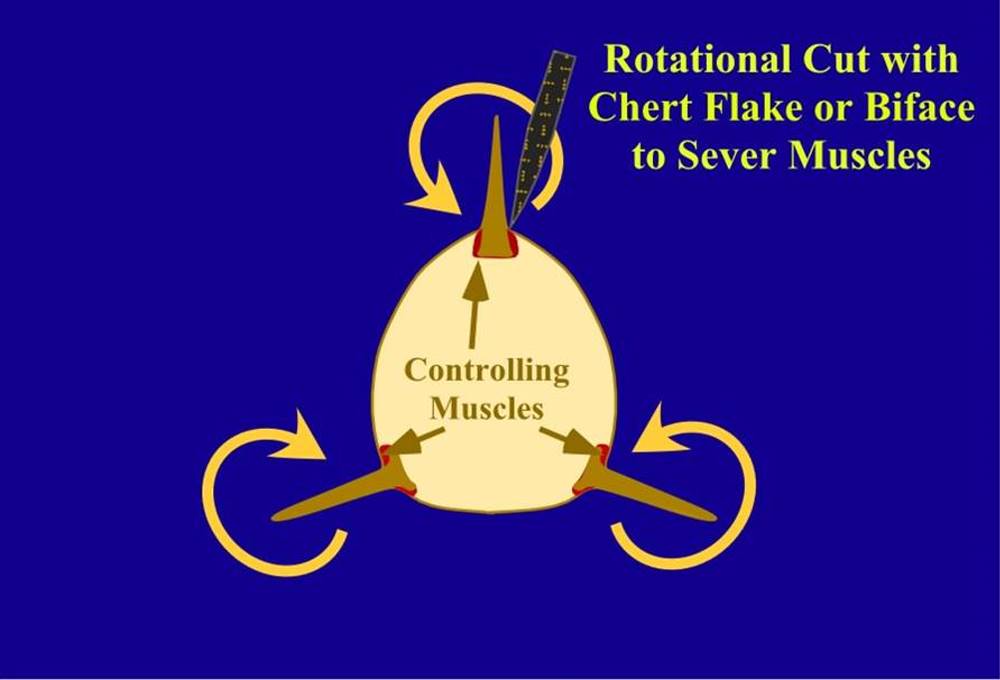

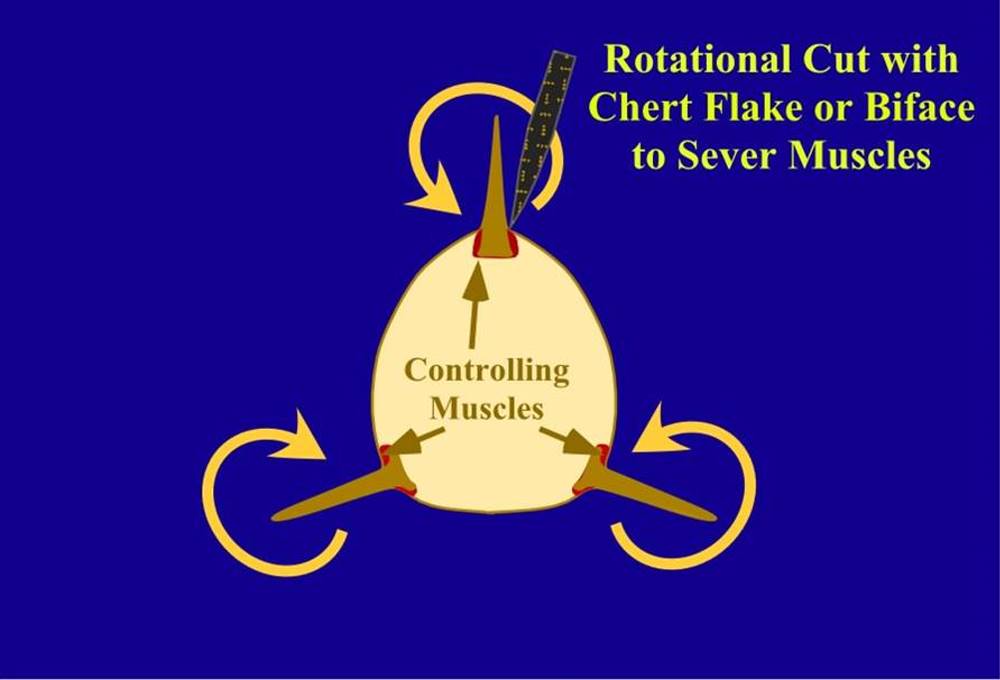

By studying "cut marks" on the fish bones from Arenosa, Jurgens made two important

discoveries. First, he found

that Arenosa’s prehistoric fishers severed the muscles at the base of

the pectoral and dorsal spines of the fish with chert flakes or knives. Presumably this was done while the fish were still alive soon after

being landed by net or perhaps being speared or hooked. Severing would have disabled the muscles controlling

the fish’s defensive spines, preventing them from causing painful injury

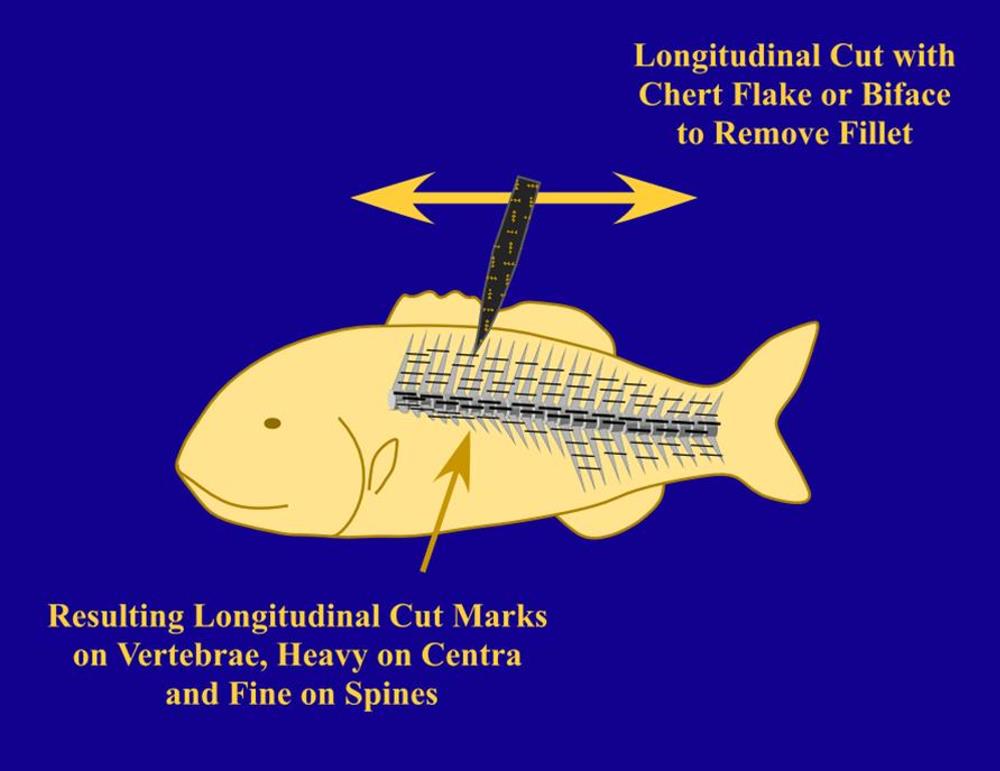

to the fisher cleaners and from damaging nets made from knotted plant fiber. Second, Jurgens discovered that many fish were carefully filleted when

butchered, rather than being quickly chopped into chunks. Clear evidence of filleting raises the possibility that fish meat was dried for storage and perhaps transported

far from the rivers where the fish were caught.

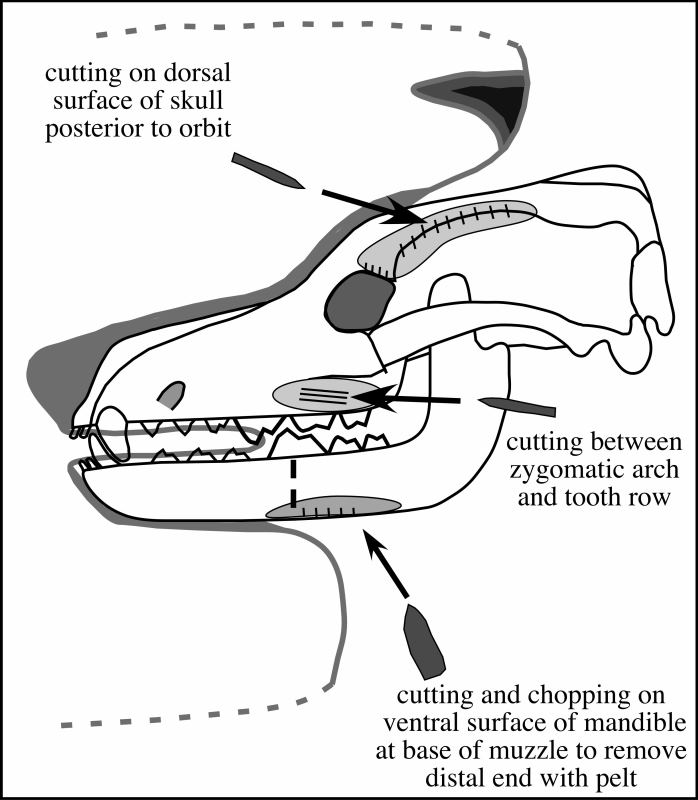

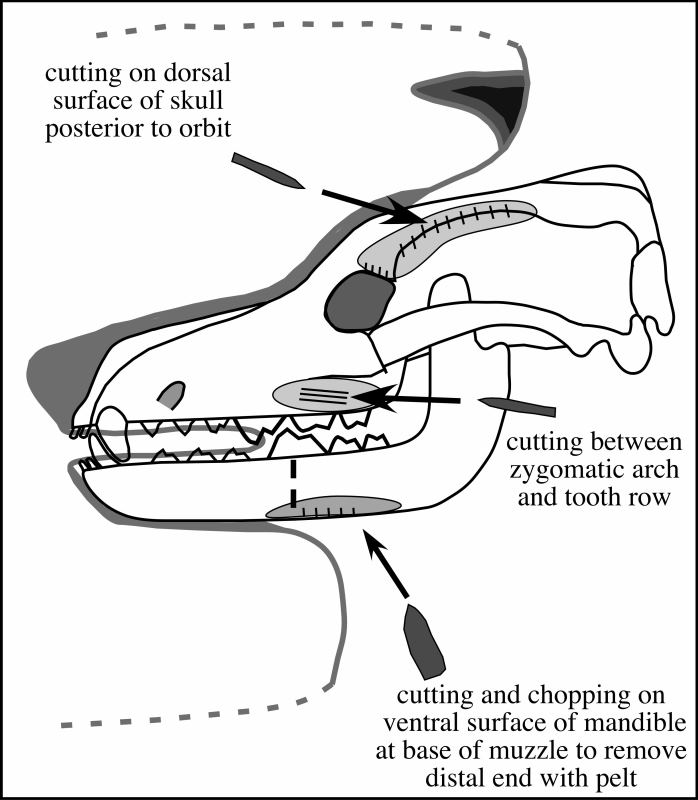

By studying cut marks on the carnivore bones from Arenosa, Jurgens was also

able to identify evidence for a specialized butchering technique known as “caping.” Caping

removes the skin of an animal while preserving the distinct facial features of its

head, including the ears and muzzle. Most of the animals skinned in this

way at Arenosa were foxes and coyotes, but some badgers, raccoons, and ringtails

were also found. After examining the faunal collections of other sites in

the Lower Pecos, Jurgens determined that caping was a common regional practice

during the Late Archaic and Late Prehistoric periods.

The skins removed from carnivores at Arenosa may well have been used

as ritual paraphernalia. Carnivores are a common motif in Lower Pecos rock art, and rock art from

the Late Prehistoric period sometimes depicts canids with powerful (and dangerous) hallucinogenic plants such

as Datura seeds. When ingested during ritual practices, Datura seeds can apparently cause canid-like

behavior, often convincing their users that they have been transformed into

canids. This belief in lycanthropy can be reinforced by tactile suggestions from animal skins. Such behaviors are common among societies with shamanistic traditions as part of ritual communication with the spirit world.

Untapped Research Potential

The work of Collins and Jurgens has done much to further our understanding

of how the prehistoric people of Arenosa lived, but there is still much that

can be learned from the site’s excavation data. A staggering 500,000 items

have been catalogued, yet most of them have never been studied. The quantities and diversity of stone and bone tools coupled with cooking features (e.g., hearths) and cooking debris (burned rocks) show that Arenosa served as a base camp were many different types of activities took place, hunting, fishing, gathering, food preparation, tool making, and ritual practices as well.

Peter Patton studied the soil monoliths taken from Arenosa

in order to reconstruct the history of flooding at the site, but most of the

hundreds of special samples taken from Arenosa remain untouched. These include

many "matrix" samples of features and of the stratigraphic layers as well as dozens of samples of charcoal and other materials suitable for radiocarbon dating.

Collins has characterized Arenosa as “the best single-site chronological

record” in the Amistad region and “one of the best in North America.” We would qualify this sweeping statement and say instead that Arenosa has potential to be so, but has not yet achieved this status. By today's standards, 32 radiocarbon assays, all of them based on sizable samples of unidentified charcoal (as opposed to more precise AMS dates done on identified specimens), would not be considered adequate to date a site with 49 defined stratigraphic layers spanning at least 11,000 years. A more rigorous dating strategy coupled with a more thorough analysis of the cultural materials would go a long ways toward fully unraveling the 11,000-year record of

alternating floods and human occupations.

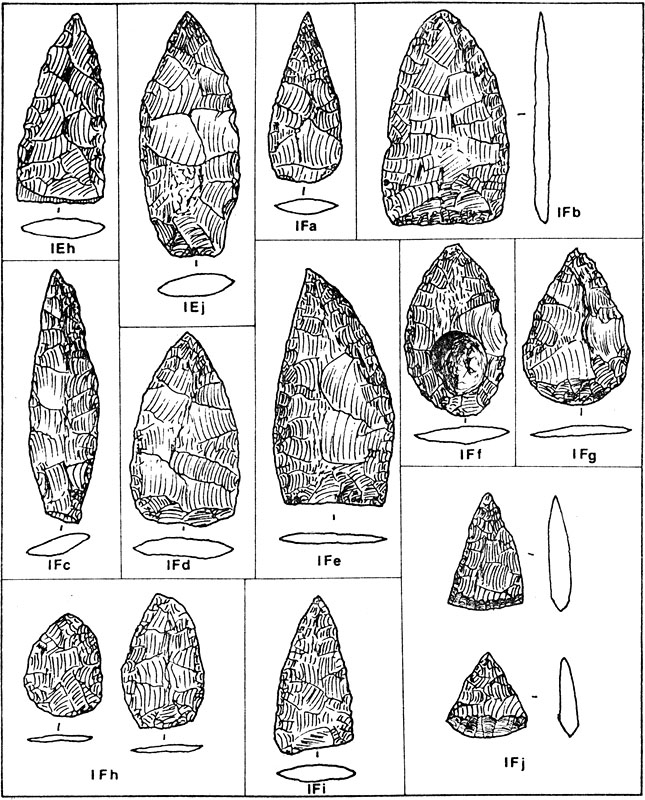

Collins' technological study of Arenosa’s chipped stone tools and debitage did not include a typological appraisal of the formal tools, especially the 2000 projectile points. Lee Bement made progress in this direction, but Arenosa's large sample from well-stratified deposits merits thorough analysis and study of the stylistic changes through time.

No study had been undertaken of Arenosa’s 121 pieces of groundstone that includes what may be the largest samples of manos (handstones) from any excavated site in the Lower Pecos. Groundstone

tools were characteristically used by prehistoric peoples to process plant materials, and their presence highlights understudied and perhaps underappreciated aspects of plant use.

Jurgens studied only about 10% of Arenosa’s 47,000 bone fragments. That sample was subject to collection bias created by the minimum 1/4-inch screen mesh size used during the excavation. In other words, many of the smallest bones were not recovered, incuding many of the most environmentally sensitive species. No attempt has been made to recover and analyze microfauna (tiny bones) from the many soil samples collected from Arenosa. Other unstudied faunal sets include the nearly 9,000 mussel shells and 32,000 snail shells found at the site. Collectively, the faunal materials have the potential to reveal much more about the diets and foraging practices of the people of Arenosa, as well as about the paleoenvironments of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Arenosa’s 141 painted pebbles have also received only limited attention.

Shirley Mock analyzed the motifs of some of Arenosa’s painted pebbles,

but included painted pebbles from several other sites in her study without

making any spatial or temporal distinctions. Much could be learned from studying

all of Arenosa’s painted pebbles with regard to changes in their designs

through time.

Without a comprehensive analyses and full reporting of the 1960s excavations, the long-recognized potential of Arenosa Shelter to help improve our understanding of the cultural and environmental history of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands will go unrealized. Fortunately, the collections and records are properly curated and archived at the Texas Archeologial Research Laboratory on behalf of the Amistad National Recreation Area of the National Park Service. These materials are available to be further studied by qualified researchers. |

A generalized flow model for the production of chipped stone tools. Chipped stone tool manufacture begins with the acquisition of raw materials and passes through one or more of the following steps: initial reduction, primary trimming, secondary trimming, and maintenance and modification after use. Graphic from Collins 1974, Fig. 15. |

Shumla-like dart point with tale-tell signs that the artifact was treated with heat during manufacture. Namely, the reddish hue and the and the glass-like luster (which does not show very well in this photo). Collins found that heat treating was used as an "adjunct" to the production of bifaces at Arenosa throughout most of the site's history. Specimen AMIS-3866.

|

Examples of final reduction stage bifaces from Arenosa. These are "finished" tools that probably served as knives or as final-stage preforms that could have been notched as dart points. Collins 1974, Figure 95.

|

Detail of Monolith 4 during geologist Peter Patton's examination of the soil samples from Arenosa. A dark, carbon-stained cultural layer can be seen at the three-foot (F3) mark, sandwiched by sandy flood layers. Photo by Peter Patton.

|

Bone tools from Arenosa. Jurgens found that mammal, fish, and bird bones were used as raw material to make tools and beads, but that mammal bones were used most often (about 85% of the time). These tools were made from artiodactyl (deer or antelope) long bones. AMIS-9536b.  |

Tools made from large catfish pectoral spines. These relatively informal implements were used to separate the fiber from desert succulent leaves or manufacture cordage and textiles. ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.  |

Incised bone bead from Arenosa. The people who made the site's beads strung them on plant fiber cordage and sinew for ornamental purposes, and sewed them onto plant fiber-based textiles and hides for decoration. AMIS-9195.

|

Bone bead manufacturing sequence followed at Arenosa Shelter as reconstructed by Chris Jurgens. Jurgens 2005, Figure 32.

|

In order to avoid painful injury from the defensive spines of catfish, Arenosa's prehistoric fishers severed the controlling muscles at the base of the pectoral and dorsal spines of the fish with chert flakes or bifaces. Image courtesy Chris Jurgens.  |

Many of the fish caught at Arenosa were filleted when butchered, raising the possibility that the meat was dried, stored, and transported far from the rivers where it was caught. Image courtesy Chris Jurgens.  |

By studying cut marks on the carnivore bones from Arenosa, Jurgens was able to identify evidence for a specialized butchering technique known as �caping.� Caping removes the skin of an animal while preserving the distinct features of its head, including the ears and muzzle. Graphic from Jurgens 2005, Fig. 34.  |

View of Arenosa disappearing below the waters of Amistad Reservoir in January 1970. ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|