In this circa 1930s photo, an early

researcher tests Alibates flint amid thick scatters

of quarry debris. Photo by A. T. Jackson.

|

These reddish stones may have been

chosen by ancient knappers for their unusual banding.

The bifacial tool in the center has the look of beefsteak.

Photo by Milton Bell.

|

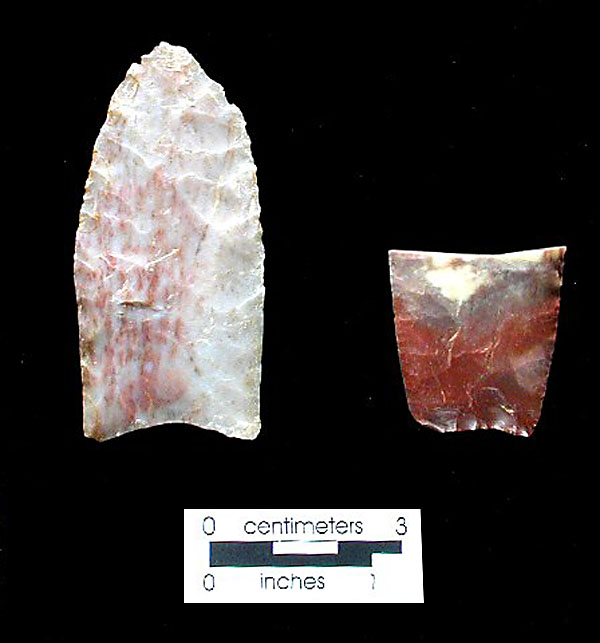

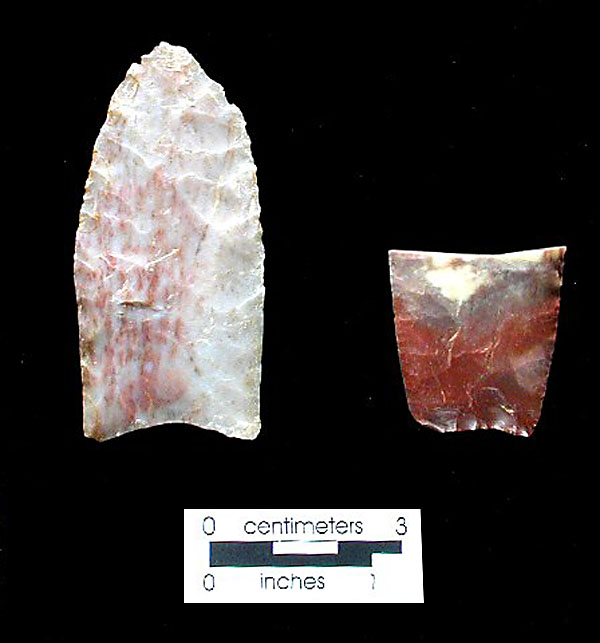

Paleoindian dart tips of Alibates

flint. A Clovis point (left) and broken base of another

show types of stone chosen by occupants of the Blackwater

Draw site. Photo by Milton Bell.

|

These colorful Alibates flint arrow

points were made by Late Prehistoric folk who lived

and hunted in the area around 800 years ago. Photo by

Milton Bell.

|

Floyd Studer points across still-open trenches at Alibates 28 during aJuly 26, 1945 visit by archeological dignitaries. Behind Studer from right to left: Alex Krieger, Clarence Webb, and Clarence Webb, Jr. Photo from TARL Archives.

|

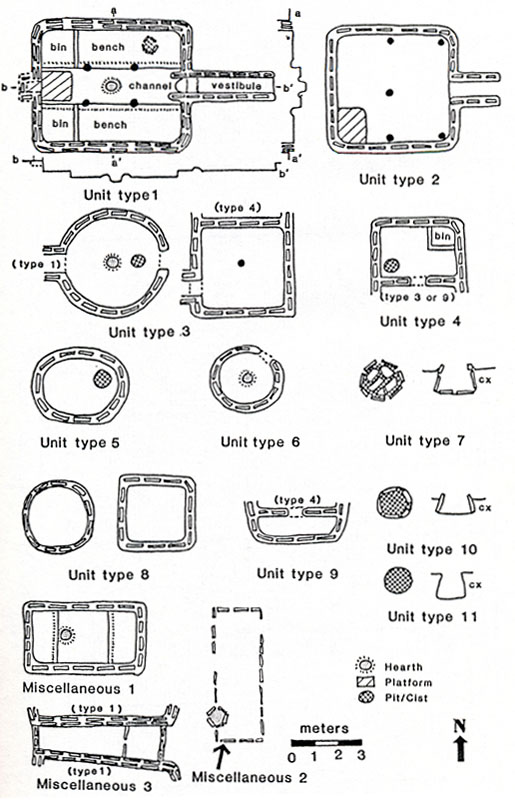

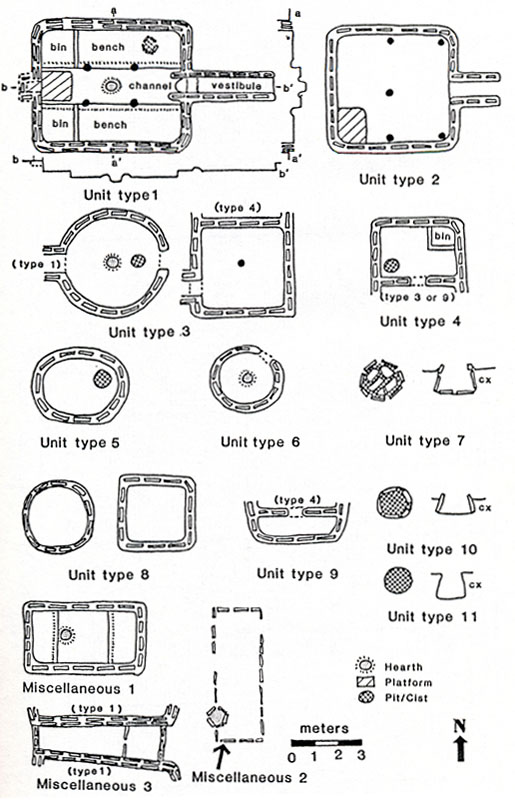

Variations in architecture in Antelope

Creek dwellings, as identified through a study of the

excavated ruins by Dr. Christopher Lintz . Drawing courtesy

of Dr. Lintz and the Oklahoma Archeological Survey.

|

|

Along the sloping canyon rims of the Canadian River

Valley in the Texas Panhandle are signs of an industry that

has spanned the course of human history in North America.

Small pits and literally tons of stone manufacturing debris

bear mute testimony to perhaps 13,000 years of quarrying a

brilliantly colored stone known as Alibates flint. So prized

was the material that prehistoric hunters traveled—or

traded—over distances of a thousand miles or more to

obtain it. Projectile points and other tools made of Alibates

stone have been found in sites as far north as Montana, as

far south as Central Mexico, and east to at least the Mississippi

River.

Archeologists for years have puzzled over the

scale and range of prehistoric activities that created these

remarkable sites. It is likely that some workers in search

of flint merely picked up exposed chunks or cobbles lying

on the ground. In fact, knappable cobbles of Alibates have

eroded down the Canadian River into western Oklahoma and as

far as Fort Smith, Arkansas. Other, more enterprising, workers

chiseled boulders directly from the bedrock. Their quarrying

activities left holes ranging from small depressions to broad

pits ranging from 5 to 20 feet across and up to 2 feet deep.

But what catches the eye for hundreds of yards beyond the

pit perimeters are the quarry wastepiles and tool-making debris

blanketing the hillslopes: thousands of quarried chunks, tested

cobbles, flakes, and tools in various stages of production.

Although termed "flint," the stone

is technically a silicified or agatized dolomite occurring

in Permian-age outcroppings. These deposits, exposed as slightly

undulating layers, are unique to the Panhandle area. But regardless

of what the stone is called, none of the terms captures its

startling beauty. In hues and tones of the evening sky, colors

range from pale gray and white, to pink, maroon, and vivid

red, to orange-gold and an intense purplish blue.

Patterns in the stone are varied as well. Bands

of alternating color create stripes and a marbled effect.

Researchers have speculated about the statistically significant

occurrence of red Alibates in sites, and whether the color

might have invoked magical connections to the blood of animals.

Clearly it was the exotic appearance of Alibates flint rather

than its workability that attracted prehistoric toolmakers.

Modern-day knappers report that the material has a resistant

quality and hardness which makes it more difficult to flake

and shape into tools than other stone, such as the Edwards

cherts found abundantly in the Edwards Plateau to the south.

Trade or Travel?

Based on evidence at the Alibates locale and at sites

further afield, prehistoric peoples throughout the millennia have

used stone from the quarry to make tools and weapons. Late ice-age

hunters apparently sought the material to tip the weapons used to

kill now-extinct large game animals. Finely flaked and fluted Alibates

flint projectile points were found at the Blackwater Draw site in

eastern New Mexico. The scene of a mammoth kill, the site dates

to 13,000 years ago at its earliest level.

Prehistoric hunters about a thousand years later

left behind Alibates flint projectile points of a different

style as well as a variety of other tools at the Plainview

site in what is now Hale County, Texas.

There is more evidence to suggest that later visitors to the quarry

mined the quarry stone more intensively than their forebears. They

used Alibates flint to outfit all parts of their "toolkit"

as well as to trade for other materials from other areas.

Ruins of Early Villages

Near the quarry site and along the Canadian River

valley are ruins of complex slabhouses and small villages attributed

to the later peoples who lived in the area from about A.D. 1150

to 1450 or later. Their culture, termed the Antelope Creek phase

by archeologists, is believed to have developed from indigenous

Plains Woodland groups who moved south into what is today the Texas-Oklahoma

panhandle region. Some researchers believe the migrants were drawn

by the water reserves of the Ogallala aquifer. The Antelope Creek

folk built their homes and hamlets close to springs or near the

river and were able to cultivate crops—beans, corn, and squash—on

a small scale. Nonetheless, hunting and gathering remained an important

part of their livelihood.

Various farming-related artifacts and other types of evidence speak to a transitional time in the

area's cultural history when hunting and gathering peoples became

more settled, planting small fields, making pottery, and trading

within large networks. In exchange for Alibates chert and bison

products, Antelope Creek people received painted pottery, shell

and turquoise jewelry, pipes, and obsidian from groups in the southwest

and to the north.

Archeologist Dr. Christopher Lintz has conducted an

extensive study of the Antelope Creek culture, tracking changes

over time in the size, architecture, interiors, and lay-out of Antelope

Creek houses and hamlets. His studies—some based on WPA-era

excavations of ruins at Alibates—reveal complex and interesting

modifications within house interiors that would not be evident to

visitors to the ruins today. These features clearly were designed

to improve daily work and comfort as well as to stave off the vicissitudes

of nature. In some houses, stone benches lining the walls were perhaps

used for sleeping and work platforms; storage pits were filled with

foodstuffs in advance of winter. Central hearths were used for cooking

as well as to provide warmth, whereas entryways, or vestibules,

were carefully designed to trap cold air. In some houses, recessed

floor channels extend from the doorway through the center of the

house, encompassing the central hearth, and ending in a raised platform

perhaps designed as an altar. Lintz believes these channels were

dug to contain debris from the work area activities and prevent

it from spreading into the sleeping areas. In all, Lintz identified

11 different patterns of house types.

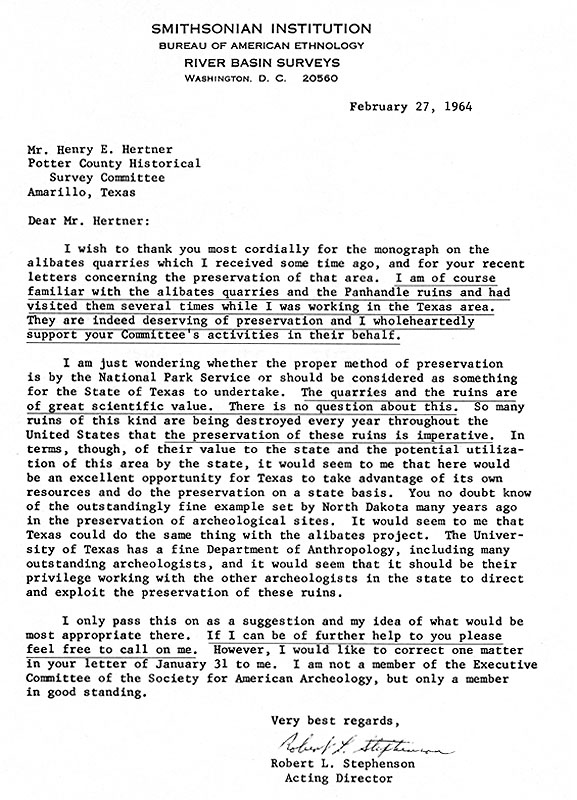

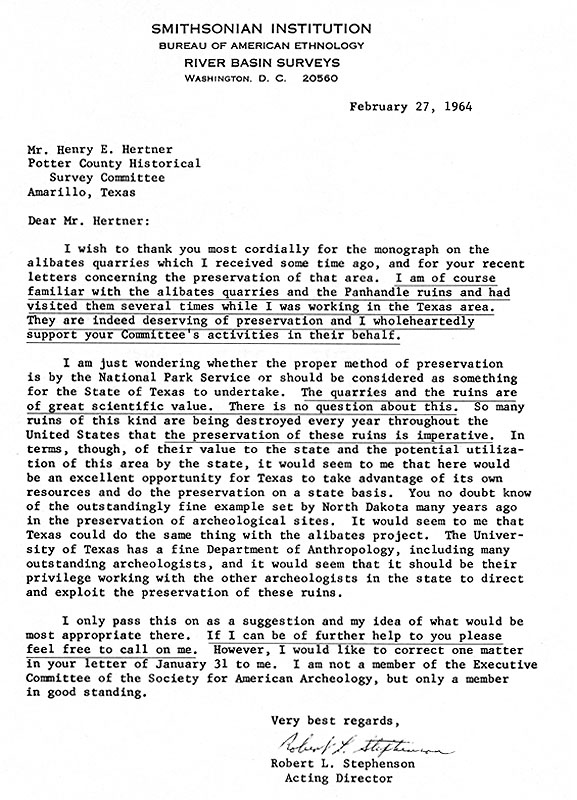

Today, these important village ruins and quarry

sites are protected and preserved, thanks to the efforts and

foresight of the Potter County Historical Survey Committee

and concerned individuals. In the early 1960s, then-vice-chairman

Harry Hertner mounted an extensive campaign to bring the site

to the attention of Congress. With letters of support from

noted archeologists across the country and with Sen. Ralph

Yarborough and Rep. Walter Rogers carrying the legislation,

the Alibates flint quarries were established as a national

monument, the only such site in Texas. The Visitor Center for Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument is on Cas Johnson Road off of Highway 136 between Amarillo and Fritch, Texas. Arrangements for tours of the quarries Monday-Friday may be made by calling 806-857-3151. More information is available on the NPS website.

|

Unusual colors are a trademark of

Alibates flint. Photo by Milton Bell.

Click images to enlarge

|

Other stones have speckled concentrations

of color creating mottled or parti-colored patterns.

Photo by Milton Bell.

|

A large mottled-red cutting blade

(left) and dart point of white Alibates were among artifacts

found at the Plainview site. Photo by Milton Bell.

|

Game might have been butchered and

processed with large, beveled-edged knives such as these

of banded-white Alibates flint. Photo by Milton Bell.

|

Hide-scraping and other tasks could

have been accomplished with these small, steeply edged

flake tools which some archeologists term "thumbnail

scrapers." Photo by Milton Bell.

|

Floyd Studer poses in front

of Alibates Ruin 28. The image label reads: "Partly excavated pueblo

ruin (digging by Studer, Mason, Moorehead, et al.) Photo

by A.T. Jackson, 1935." The sign on the far right warns trespassers

against disturbing the site. Photo from

TARL Archives.

|

Letter from Smithsonian archeologist

Robert L. Stephenson, one of many pleading the case

for national monument status for the Alibates Quarries.

|

|