The McMillan Site (41ML162)

The excavations at the McMillan site revealed multiple, periodic occupations over a time period of nearly 5,000 years. Five analysis units were identified: the lower two units (Analysis Unit 4 and Analysis Unit 5) contained evidence pertaining to occupations during the early Late Archaic and late Middle Archaic periods, repectively. Analysis Unit 2 represents the latter part of the Late Archaic, and Analysis Unit 1, the Late Prehistoric Toyah interval. There was no evidence of occupations during the Austin interval of the Late Prehistoric.

Among the five analysis units, there are some general consistencies as well as differences. Four of the analysis units yielded 39 features, of which 87 percent (n = 34) are in Analysis Units 2 and 3. Overall, basin-shaped and flat hearths (n = 27, 69 percent) are most common and constitute between 65 and 100 percent of the features identified in the three analysis units in which they are present. At least two (Features 11 and 41) in Analysis Units 2 and 3 appear to be earth ovens based on their size (approximately 150 cm in diameter each) and rock densities (201.5 and 76.85 kg, respectively). Although neither contains geophytes, bulb fragments are present in other similar-sized and smaller basin features, indicating their availability at the site or nearby. Several large and small hearths contain many highly fragmented unidentifiable bones and charred wood of oaks and other nut-bearing trees. Fatty acid residues from these features are usually consistent with seeds/nuts and the fatty meat and possibly rendered fat of medium-sized mammals. The hearths and their contents indicate that various reliable resources were processed at the McMillan site.

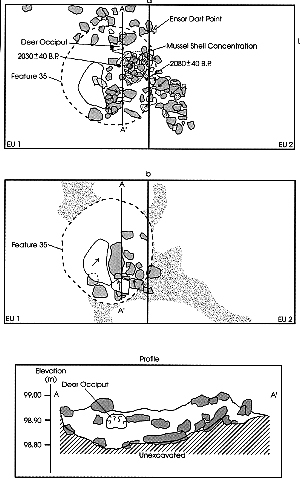

One small pit (Feature 35) is distinguished from the basin-shaped hearths based on its possible use as more than a cooking or heating facility. The pit’s diameter is less than 70 cm, and it is approximately half as deep as it is wide. This small feature contains several burned rock layers and two large unburned rock slabs, a pocket of scattered mussel shells, and a highly variable and mostly unburned bone assemblage, along with charred wood, bulbs, and a spurge seed.

Other features such as burned rock concentrations, charred wood , possible post molds, refuse dumps, and a stain each account for 10 percent or less of the entire feature assemblage. Most of these features appear to be the residue of cooking activities or are associated with hearth features. The kinds of materials associated with the nonhearth features do not deviate from those materials found in the hearths. In Analysis Units 1–3, cultural materials are densest in and around features, particularly hearth features, indicating that many site activities were centered on hearths. Analysis Units 1–3 also contain refuse dumps, suggesting that areas of the site were maintained and cleared of debris, an activity indicative of relatively lengthy occupations.

The densities of materials also provide evidence regarding the lengths of site occupations. What stands out is that the highest and lowest densities of all material classes are in Analysis Units 2 and 5, respectively. All material classes are at least 2.5 to 4.3 times more abundant in Analysis Unit 2 than in the other analysis units. Except for unmodified bones, which are very infrequent in Analysis Unit 4, all classes of material occur in moderate densities in Analysis Units 1, 3, and 4. This suggests that the low density of unmodified bones in Analysis Unit 4 is a matter of poor preservation. The frequencies of burned rocks and faunal remains in Analysis Units 2 and 3 are probably related to the plethora of features (particularly hearths) and the items processed.

Although the greater numbers of materials within each material class in Analysis Unit 2 suggest greater use intensity or longer-term occupations, a better measure of relative length of occupation may be the ratio of unmodified debitage to finished formal bifacial tools (excluding indeterminate bifaces). This measurement is based on the assumption that the use lives of most formal tools exceed the duration of most short-term occupations, meaning that longer-term occupations should result in the more frequent discard of formal tools. Lower ratios would indicate longer occupations, while higher ratios would suggest shorter occupations. In comparing unmodified debitage to finished formal bifacial tools (minus indeterminate bifaces), the two lowest ratios (38 to 1 and 30 to 1) are in Analysis Units 2 and 5, respectively. Conversely, higher ratios (48 to 1 and 62 to 1) occur in Analysis Units 1 and 4, with Analysis Unit 3 in the middle at 41 to 1. The ratio for Analysis Unit 2 suggests that the ubiquity of the lithic materials do correlate to longer occupations. The relatively high ratio expressed for Analysis Unit 1 appears to conflict with other data that suggest a long-term occupation. Clearly no one measure or piece of evidence can fully determine or indicate the duration of occupation or use intensity at a site.

Stone Tools

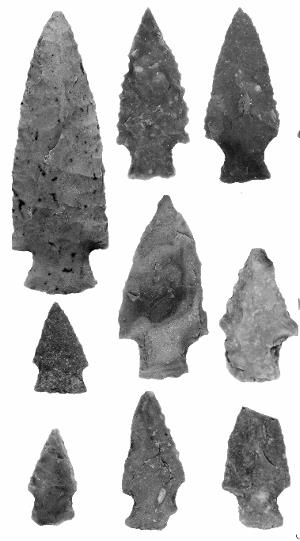

The following discussion of chipped stone tools primarily centers on Analysis Units 1–3 because they contain large assemblages, but it also includes Analysis Units 4 and 5 where relevant. A higher number of expedient than formal tools is present in each analysis unit, and expedient tools are approximately 1.8 times more common in Analysis Units 2–4. The frequencies of expedient tools are triple and nearly quadruple the numbers of formal tools in Analysis Units 1 and 5. Of the functional formal tools, dart points are most common across all analysis units, but slight differences in the rest of the tool kits are apparent. Equal counts of knives and either multifunctional tools or scrapers occur in Analysis Units 1 and 2, whereas scrapers are almost double the number of knives in Analysis Unit 3. The ratios of bifacial and unifacial scrapers to dart points and scrapers to utilized flakes are 1:1.5 and 1:15.7 for Analysis Unit 1, 1:1.7 and 1:8.0 for Analysis Unit 2, and 1:1.3 and 1:5.7 for Analysis Unit 3. While the relative frequencies of scrapers and dart points remain constant between the three units, utilized flakes decrease in relative frequency with increasing age. The preponderance of projectiles and scrapers (possibly multipurpose tools), along with knives, suggests that procurement and processing of game were fundamental. The high ratio of utilized flakes for the Toyah component versus the Late Archaic occupations is curious given that hunting was such a key activity at that time and was typically accomplished with a specialized kit of formal tools. The same tool ratios for Analysis Units 4 and 5 are 1:3 and 1:6 and 0:4 and 0:19. This could reflect the exploitation of other kinds of food resources, although small sample sizes limit serious interpretation.

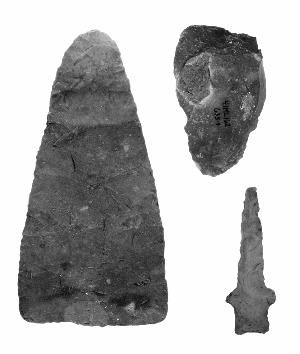

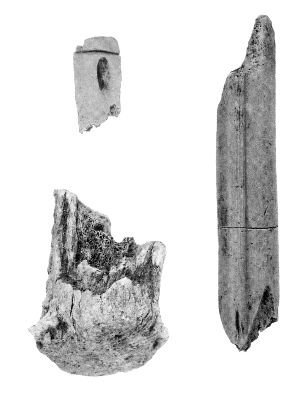

Specific attribute data and additional artifacts provide evidence of other onsite activities. Of the 205 bifaces (minus indeterminate pieces), 98 are finished and 59 are late-, 39 are middle- and 9 are early-stage specimens. Finished bifaces are most common in each analysis unit (excluding Analysis Unit 5), and only Analysis Units 2 and 3 yielded moderate numbers of middle-stage and several early-stage bifaces. Between 63 and 89 percent of the utilized flakes and 80 to 85 percent of the unmodified debitage from the analysis units are composed of flakes no more than 1.0 inch size and retaining 50 percent or less cortex. The biface, utilized flake, and unmodified debitage attributes primarily attest to tool production and maintenance. Intense resharpening among the dart points as well suggests that most formal tools were brought to the site as finished and late-stage specimens, with some close to the end of their use lives after being used at multiple locales across the landscape. Some of the data, however, demonstrate that early-stage reduction also took place, at least in a limited fashion.

Three analysis units each produced a core or one ground or battered stone, and two others generated abundant quantities. Analysis Unit 2 contains 8 cores and 19 ground and battered stones, while Analysis Unit 3 yielded 20 and 30, respectively. Furthermore, almost three-fourths of the ground and battered stones are manos, hammerstones, and indeterminate groundstone. The cores and hammerstones and few cobble tools indicate that some raw material was transported to and reduced onsite. Additionally, the presence of grinding implements and some smaller hammerstones that might have been used as pecking stones to form or refurbish grinding implements suggest plant food processing.

Although present in limited numbers, ceramics, bone tools (primarily awls and possibly needles), and cut or drilled mussel shells are associated with the Toyah phase and later Late Archaic components. Modified bones composed of antler billet and other probable tool fragments are also associated with Analysis Unit 3.

Animal and Plant Remains

Hunting was geared toward ungulates, particularly deer, based on the vertebrate faunal assemblages associated with Analysis Units 1–3. Approximately 60 to 70 percent of the identifiable bones represent deer, deer family, pronghorn antelope, canid- to deer-sized mammals, and deer- to pronghorn-sized artiodactyls. Plains bison or deer- to bison-sized mammals are present in Analysis Units 1–3, but they primarily occur in Analysis Unit 1, the Toyah component. Butchering of these remains and subsequent marrow extraction is evidenced by specimens with cut or fillet marks, the high percentages (41 to 57) of spirally fractured bones, particularly marrow-rich appendicular elements, and impact fractures on several bones. Intensive use of deer and other ungulates is also evidenced by the large quantities of unidentifiable bone fragments from discrete contexts, which may indicate grease rendering. While unidentifiable, only the bone fragments from these larger game animals yield large quantities of grease.

Lower-ranked resources occur in moderate numbers and include rabbits, hares, and rabbit- to canid-sized mammals, along with various fish species, although the two groups comprise less than 15 percent of the assemblage. Turtles are also common, but their numbers may be exaggerated due to the number of small shell fragments. The inclusion of these resources is indicative of a wide diet breadth and suggests that the occupations were relatively lengthy. As the occupation span became longer, the acquisition of higher-ranked resources such as deer became cost-prohibitive, and lower-ranked resources were added to replace them.

The invertebrate faunal remains consist of more than 11,500 unmodified mussel shells, of which 16 percent were analyzed. Ten different species are in the assemblage, with Threeridge comprising more than 50 percent of the valves in all analysis units. Pistolgrip, Smooth Pimpleback, and Tampico Pearlymussel are also common. Shells with eroded umbos led to a greater number of unidentifiable valves in each consecutive analysis unit, indicative of poorer preservation. Although great quantities of mussels were gathered and consumed, they are nutritionally poor in terms of calories and protein and therefore were never a major food source; they probably were used simply to augment the diet. The presence of mussels in dense beds in shallow waters may be the primary reason they were used, as acquisition costs would be relatively low if small quantities were gathered on a daily basis for meals.

Macrobotanical remains from 14 features associated with Analysis Units 1, 2, and 3 were analyzed. (Features in Analysis Units 4 and 5 were not suitable for sampling because of poorly preserved organic materials or insuficcient context.) Eleven named wood types are present, with plateau live oak and white oak occurring in each analysis unit. Seven other wood types co-occur in Analysis Units 2 and 3, and only red oak and walnut in Analysis Unit 2 and elm/hackberry and plum/cherry in Analysis Unit 3 are exclusive. The woods are indicative of a riparian hardwood forest, except for juniper and plateau live oak, which thrive on the uplands and valley slopes. Many of the charred wood samples indicate that oaks and other nut-bearing trees were pervasive, and plum/cherry and hawthorn constitute other food-producing trees. Charred samples of possumhaw/yaupon suggest that Ilex vomitoria used to brew Indian black drink, an emetic used by Native Americans during ceremonial events, may have been present in the site area. Seeds and bulbs are infrequent, yet they indicate plants with edible parts (hawthorn, pokeweed, and camas) in addition to those with medicinal properties (pokeweed and spurge family).

Bulb fragments found in features associated with the Toyah phase and Late Archaic components are consistent with the camas identification. Other archeological sites in Texas that have yielded camas are Armstrong, Blockhouse Creek, Firebreak, Horn Shelter, Rice’s Crossing, and Wilson-Leonard, in addition to a group of eight sites at Camp Bowie in Brown County. These sites are located in the Lampasas Cut Plain (or in the case of the Camp Bowie, just west of the Lampasas Cut Plain) and Blackland Prairie, and associated radiocarbon dates span the Early and Late Archaic periods, as well as the Austin phase of the Late Prehistoric period. The McMillan site is the only known site where possible camas has been recovered from a Toyah-age context.

Fatty acid residues from feature-associated burned rocks from Analysis Units 2–4 corroborate several findings within the vertebrate faunal and macrobotanical assemblages. Residues from Analysis Unit 2 are similar to a variety of plant and animal resources, including seeds and nuts, low-fat roots, the fatty meat of medium-sized animals, and possibly rendered fats. The results for Analysis Unit 3 consist solely of nuts and seeds, while those for Analysis Unit 4 are comparable to low-, moderate-, and high-fat-content plants and the fatty meat of moderate-sized game.

Summary

Multiple components at the McMillan site span nearly 5,000 years from the late Middle Archaic to the Toyah phase. The chronometric data do not reflect a continuous occupation of the site, with a hiatus indicated during the Austin phase, just prior to the Toyah occupation. The bulk of the stone tools, vertebrate fauna, macrobotanical remains, and fatty acid residues in Analysis Units 1–3 substantiate that deer and deer-sized animals were a significant part of the inhabitants’ diet. Together, the assemblages support hunting and the subsequent intensive processing of carcasses, including marrow extraction, grease rendering, and possible pemmican production, as vital subsistence activities. Hearth features, particularly basins, indicate that plant foods such as geophytes were locally available in dense and reliable patches once the floodplain surface stabilized (after Analysis Units 4 and 5). Seasonal indicators of camas and similar bulbs correlate to possible spring occupations. Supplemental food resources include birds, fish, turtles, mussels, and small mammals such as rabbits, hares, and rodents. In all, the site occupants using these resources stayed at the site for relatively lengthy periods of time, carrying out many of these activities in and around hearth features, and at times even maintaining site areas by sweeping them of debris.

Although possibly attributable to sample size and poor bone and organic preservation, the older components corresponding to Analysis Unit 4 and 5 may represent a difference in the targeted resources. This difference may be the result of a more dynamic depositional environment and less-stable occupational surface, resulting in shorter occupations and the availability of different kinds of resources.

|

|

|

|

|

|