The Higginbotham Site (41ML195)

National Register testing excavations conducted at the Higginbotham site in 2001 encountered a discrete cultural deposit buried more than 2 meters below the terrace surface. Data recovery excavations by Prewitt and Associates targeted this single component, and refined the time of occupation and the nature of activities that took place there. Cultural features yielded overlapping calibrated radiocarbon dates that range from 1270 to 380 B.C. The geomorphic and chronological evidence indicate that the inhabitants camped on the bank of the North Bosque River during the early half of the Late Archaic period. Given the depositional environment (an aggrading point bar) and relatively discrete and thin nature of the cultural deposit, the actual time span represented by the occupations may be less.

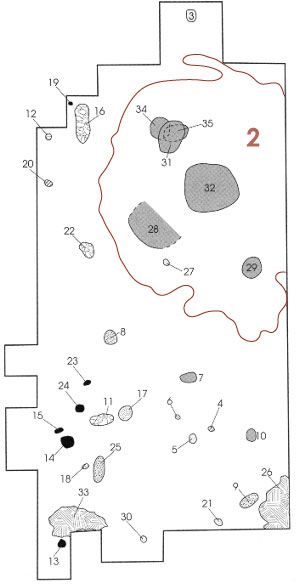

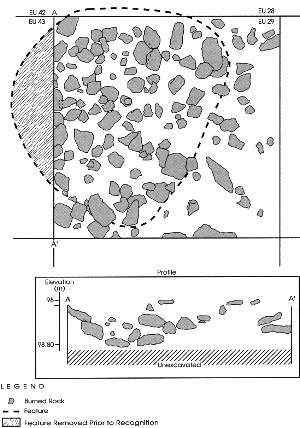

The inhabitants of this site conducted an apparently limited range of activities, chief among which was plant baking. The principal feature at the site is a well-defined incipient, or early stage, midden with a burned rock density almost 12 times greater than all other contexts. Measuring 9 m by 6 m, this large feature encompassed six basin-shaped hearths and one flat hearth. Other features included small family hearths and refuse dumps, as well as areas where butchering of deer and other animals took place.

Although the cultural deposit at Higginbotham averages 65 cm thick, a zone of recurrent and perhaps intensive use occurs between 98.00 and 97.70 m. Fifty-nine percent (n = 20) of the features, including the burned rock layer and its internal features, cross cut this 30-m-thick zone. Additionally, 88 percent (n = 5,688) of the artifacts, 87 percent (n = 330) of unmodified bones, 74 percent (25,638) of unmodified mussel shells, and 81 percent (494.4 kg) of the burned rocks from nonfeature contexts are found here.

Spatial patterning of the material culture is apparent, with artifacts concentrated in the southern third of the excavation block. Similar patterning can be seen with the animal bone, with unmodified vertebrate and invertebrate remains most common outside of the limits of the burned rock midden, Feature 2. There were very few burned rocks found outside of features. This suggests that the prehistoric campers maintained the areas between the family hearths and cooking areas and kept them free of debris for other activities. These activities include the manufacturing and maintenance of chipped-stone tools and cooking in smaller, informal features.

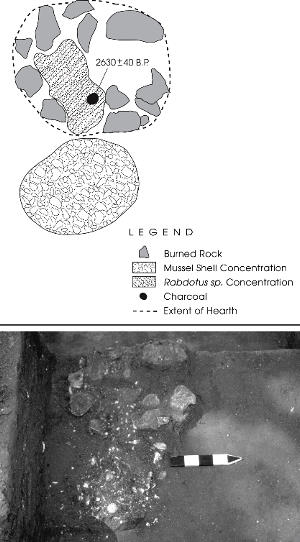

Although the burned rock midden (Feature 2) contains a few artifacts, it contains greater numbers of unmodified bones and mussel shells, particularly along the periphery of this incipient midden. The burned rock layer of Feature 2 clearly demarcates an area where the primary focus was repeated use of earth ovens for extended cooking times. The number of earth oven uses represented in this feature is unknown. One result of repeated use of earth ovens is the fracturing and breaking of the rocks. Archeologist Steve Black, citing descriptions of modern sotol processing, suggests that four firings may occur before the oven has to be rebuilt with new rocks. Experimental researchers have noticed significant rock breakage after two firings of their earth oven. Given that Feature 2 contains seven internal hearth features that are recognized due to the sizes of their rock constituents, we can estimate that Feature 2 witnessed at least 14 to 28 cooking events. Whether these firings occurred all at once during one occupation or over several occupations is not known.

Chipped-Stone Weapons and Tools

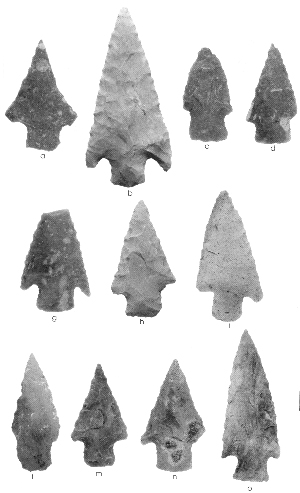

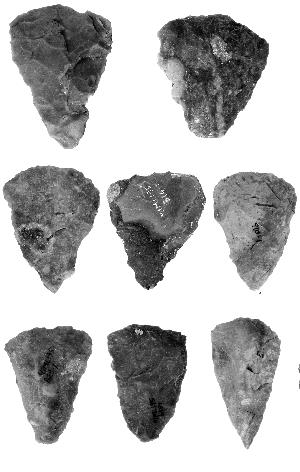

The array of chipped stone tools from the Higginbotham site is narrow. About 13 percent (n=61) are dart points, while bifaces account for almost 27 percent and utilized flakes 60 percent. Few cores are present, and unifacial tools are absent. The bifacial tool types are dominated by intensively used and extensively resharpened dart points, knives, and adzes, many of which appear to be near the end of their use lives.

Fifty of the projectiles had uniform basal elements and morphology but did not fit neatly into any type; accordingly they were classified as Untyped Group 1. With the absence of other better-defined point types, the relationship of these Untyped Group 1 darts to types found at other sites in the region and surrounding regions is unclear. Although morphologically similar to Delhi points of southeast Texas, It is more likely that the Untyped Group 1 points are associated with a regional tradition of long thin triangular-bladed darts with straight stems (e.g., Bulverde, Carrollton, Yarbrough) and are simply a later localized variant of these earlier, more widespread styles. Almost all of the dart points, particularly those of Untyped Group 1, exhibit an interesting pattern of maintenance or resharpening. There appears to have been a tendency to emphasize blade symmetry, while maintaining a high blade width/length ratio and very sharp distal tip.

Eleven bifacial adzes were recovered. These also display a high level of intensive resharpening, but the working edges for the most part remain very symmetrical. Use wear on the working edges is bifacial, and not as intense as might be expected for tools used in heavy chopping and cutting activities; the tools lack battered bit edges and heavy impact damage. Haft wear is also seemingly light and not typical of a tool used for heavy chopping tasks. In fact, the resharpening is more apparent than the wear along the working edges. In terms of morphology and wear, these adzes are similar to Erath bifaces, which Dee Ann Story and Harry Shafer defined from specimens previously recovered at the Baylor and Britton sites. They speculate that Erath bifaces were used to pry open mussel shells, which is an interesting interpretation given the number of similar tools and mussel shells recovered at the Higginbotham site.

Although their functions are unknown, the high percentage of utilized flakes may have been used for processing an array of materials, including wood, vegetal materials, and hides. Interestingly, none of the utilized flakes exhibit multiple use edges, and 98 percent of them are 1.5 inches or less in maximum dimension, suggesting that these tools were expended quickly for short and simple tasks. The heavily reworked lithic tools, coupled with the 97 percent of the utilized flakes and 98 percent of the unmodified debitage that measure 1.5 inches or less, indicates that tool refurbishing, edge rejuvenation, and late-stage lithic reduction were primary activities at this site. Fifty percent of the corticate utilized flakes and 20 percent of the unmodified debitage display abraded surfaces, suggesting that they were struck from cherts obtained from local gravel bars. It appears that the more formal tools (e.g., dart points, knives, and adzes) were manufactured offsite and are part of a mobile tool kit used and transported between various locales across the landscape. Such bifacial tools are ideal for highly mobile groups, as these tool types tend to be lightweight, durable, and conducive to multiple cycles of resharpening, thus extending their use lives. The high degree of resharpening observed in the site’s formal tool assemblage may not be indicative of intensive use solely at the Higginbotham site but a result of tools with long use lives used at multiple sites before they were discarded. The presence of so many formal tools discarded near or at the end of their use lives suggests that the site’s occupants were able to access, either through direct procurement or exchange, large chert cobbles for tool replacement while camped at Higginbotham, or that they simultaneously discarded tools and abandoned the site and then moved to a source area of large primary cherts. Based on the nature of the debitage assemblage (size and cortex attributes) and the cores, it seems the latter scenario is more likely.

The limited ground and battered stones mostly consist of manos and indeterminate fragments exhibiting a ground surface. The scarcity of grinding implements might be considered unusual given the occurrence of plant processing features and their associated debris, although their near-absence from many central Texas sites is not uncommon. It could be that baked geophytes did not require any processing after cooking, or if processing such as grinding and pulverizing was required, implements of perishable materials such as wood and bone were used. A number of chert cores with battered edges, however, are present in the assemblage and these could have been used for crushing, battering, and grinding tasks in lieu of well-formed and easily recognizable manos and other ground stone implements. The lack of well-formed and easily recognized ground stone tools can be viewed as a product of short-term occupations and high mobility, because these tool types are created or formed through repeated use. Short-term occupations obviously result in less use of such implements, and their weight precludes their transport from site to site, thus preventing repeated use.

Remains of Animals and Plants

Animal and plant remains, along with fatty acid residues, are indicators of diet, the immediate environment, and, to some extent, the season during which the site was occupied. Almost half (n = 225) of the identifiable vertebrates consist of canid- to deer-sized mammalian, deer- to pronghorn-sized artiodactyl, deer family, and deer elements, of which more than half (n = 121) exhibit spiral fractures suggesting marrow extraction. The deer-sized and deer elements suggest that at least two individuals, possibly one adult and one subadult, were taken, processed, and consumed at the site. Assuming that entire carcasses were transported to the site—and there are few reasons to suggest that this did not occur, since white-tailed deer are small enough for even one person to transport—the assemblage reveals some interesting things about butchering and consumption. Elements absent from the assemblage include the pelvis, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, and the cranium (though the presence of a mandible and upper teeth scattered throughout the excavation block may indicate that skulls simply are not preserved). These elements yield very little marrow, and the absence of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae suggests that butchering took place outside the excavation block area. Here, appendicular elements were removed from the carcass, distributed, and then consumed and disposed of in the area of the block. The meat and particularly the marrow associated with these elements produce some of the highest gross yields and returns in terms of kilocalories.

The consumption of meat and marrow and subsequent disposal of elements associated with the lower left hind leg of a deer or deer-sized animal is represented in Excavation Unit 61 on the western margins of Feature 2. Nearby Feature 22, a mussel shell dump, may also be associated with this meal. The remains of the lower right hind leg of a deer or deer-sized animal are represented in Excavation Unit 80 along the southern periphery of Feature 2 and may represent another individual family meal. Other appendicular elements, including a femur, humerus, and metapodial fragments, are scattered across the southern portion of the excavation block. Those elements that are absent from the assemblage, such as the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, though marrow poor, actually have some of the highest meat weight and kilocalorie yields and return rates, because they include the backstrap or loin, which runs the length of the dorsal side of both the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, and the tenderloin, which is attached to the ventral side of the lumbar vertebrae. It appears that these cuts of meat were completely removed from the axial elements during butchering and then distributed or consumed. Thus the pattern of elements observed in the excavation block represents the consumption and disposal of distributed high-yield marrow carcass parts by individuals or families, and not solely high-meat-yield parts, with the butchering taking place somewhere outside the block area. One could argue that this is due to the importance of marrow as a source of high-calorie fat, something that would have been vital for hunters and gatherers if body conditions of deer were poor due to drought or other factors that would impact their food supply.

The acquisition and consumption of small mammals appears to have been minor, as only five rabbit- to canid-sized mammalian specimens were recovered, though these numbers may be biased due to poor bone preservation. Turtles also appear to have been a minor part of the diet. Surprisingly, given the proximity to a perennial stream, fish and other aquatic vertebrates are poorly represented; however, the remains of aquatic invertebrates (freshwater mussels) are numerous. Eleven species were recognized, all of which tend to prefer larger flowing waterways rather than springs, intermittent drainages, or backwaters. This indicates that the nearby river had a perennial and fairly constant flow that sustained considerable mussel populations. The nutritional value of mussels, in terms of calories from protein and fat, is quite low compared to terrestrial game animals, but they do contain high levels of certain minerals such as calcium and iron (see Mussels section for more detail).

Mussel shell dumps associated with hearth features (Features 8, 9, and 25) contain 271, 74, and 281 shells, respectively, and are assumed to represent the remains of family meals. Based on an average yield of 9.0 calories per mussel, a daily consumption of 2,000 calories can be satisfied by consuming approximately 222 mussels. Clearly if Features 8, 9, and 25 represent family units, even a small family’s daily caloric needs would have had to include foods besides mussels. Discrete mussel shell dumps not associated with hearths (Features 11, 12, 16, and 22), but assumed to represent the remains of family meals, also suggest that meals would have had to include other foods, since none of these dumps contain more than 371 shells. These numbers suggest that a relatively small number (in terms of caloric needs) of mussels were probably collected and consumed daily by families to augment their diet. The overall number of shells recovered from the site (and their small size) also suggests that this activity occurred repeatedly. Despite the large number of shells, mussels probably were never a major part of the diet in caloric terms. Snails were another source of calories and protein. Concentrations of Rabdotus sp. shells associated with hearths and mussel shell dumps suggest their intentional collection for consumption.

Flotation samples from seven basin-shaped and three flat hearths produced charred buds, fragments of unidentifiable geophytes, nutshells, seeds, and various wood types. The role of buds, which include grass stems, is unknown, although researcheres such as Leslie Bush have noted their economic importance as well as use of grass as an insulating or packing material in pit hearths. All of the geophytes are from five hearths within the incipient midden. Most wood types identified are typical of a riparian forest. Oak, including live oak, which is a xeric species that thrives in shallow soil, is the most common wood, followed by hickory. These two slow-burning fuels provide a long-lasting, even-temperature fire necessary for the extended cooking times required for bulbs and tubers.

Together, the macrobotanical and fatty acid residues suggest that hearths at the Higginbotham site were used to prepare a variety of foods. The remains of geophytes, particularly in larger basin-shaped hearths, are consistent with ethnographic evidence from most of North America that shows that bulbs and tubers were bulk processed at critical times of the year and that the construction of these features is resource specific.

Summary

The investigations at the Higginbotham site show the area to be an important locale that foremost provided a rich and diverse food base, along with the raw materials (limestone and fuel) necessary for processing. Although potentially utilized year-round, the occupations appear to have been tied to seasons when particular resources were most available and easily obtained in mass at relatively low costs. The midden and its embedded hearths, numerous heavily refurbished projectiles (primarily composed of Untyped Group 1) and adzes (similar to Erath bifaces), prevalence of utilized flakes, missing unifacial tools, abundant mussel shells, and presence of a tuber similar to groundnut suggest a focus on readily accessible aquatic and plant resources. Other possible food resources are indicated by the charred remains of nut- and acorn-producing trees, although actual charred nut shells and grinding stones are few. The vertebrate faunal remains show that deer were the primary prey animal. Marrow extraction is evident, as approximately half of these bones are spirally fractured.

|

|

|

|

|

|