|

|

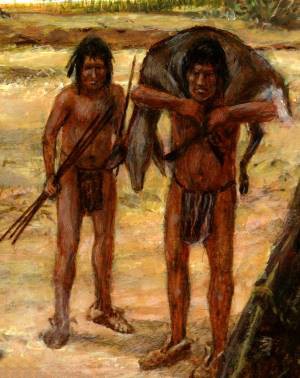

Deer Hunting

Deer were the main animal hunted by native peoples of the lower Bosque area. Deer not only provided lean meat, but the marrow inside the bones was an important source of fat and protein. The fat was later mixed with dried meat and other foods to make food that could be preserved and carried on hunting trips and from camp to camp. In addition to food, skins from the animal were tanned and used to make clothing, moccasins, blankets, and coverings for temporary shelters. Bone and antler could be fashioned into tools.

For all these reasons, deer were a highly-ranked resource in prehistoric times and the primary target of hunters in the lower Bosque River valley. At the three excavated sites, archeologists found large quantities of deer bone, much of which had been broken and crushed. These heavily fragmented remains tell archeologists that the prehistoric campers were utilizing the deer intensely for food, breaking up the bones and boiling them to get the fat or bone grease.

Deer provided the bulk of the calories and animal protein consumed by the occupants of the Britton and McMillan sites (mussels provided the bulk of the calories and animal protein at Higginbotham). Based on identifiable elements, at least seven deer are represented in the assemblages at the Britton site (two in AU 1, four in AU 2, and one in AU 3). At least six deer are present in the assemblages at the McMillan site (one in AU 1, two in AU 2, and three in AU 3), and at least two deer (one adult and one juvenile) are represented at the Higginbotham site. The importance of deer as a resource to the prehistoric groups of the lower Bosque River valley is examined further below in the context of potential population densities and the nutritional value of deer.

Favored Habitats

Deer prefer woodlands and other vegetation communities that provide cover and nutritional browse (leaves and young twigs of woody plants), forbs, and mast—a diet composition that fluctuates throughout the year, depending on plant availability and rainfall. Their favored habitat consists of a patchwork of trees and shrubs interspersed with open areas. Deer generally avoid open grasslands, as they provide neither adequate cover nor a dependable source of food. Deer are not able to digest mature grasses, although they will consume grasses when they are young and succulent. In prehistoric times, many of the Grand Prairie’s environments were grasslands or open live oak savannas and were largely maintained by wildfires, so prime deer habitat would have been limited to the riparian zones along streams. The loamy bottomlands of the lower Bosque basin—composed of an overstory of oaks, pecans, elms, hackberries, cottonwoods, and ashes and an understory of hawthorn, greenbrier, peppervine, and forbs—provide ideal habitat and cover for deer and an adequate diet of browse, mast, and forbs.

Across the Grand Prairie, modern estimates of carrying capacity range from one deer per 10–12 acres on good habitat in the Cross Timbers area to as little as one deer per 25–30 acres or greater in areas with less than optimal habitat, based on Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPWD) studies. To the east in the Post Oak Savannah, riparian habitats along stream courses will support one deer per 10 acres. Although deer populations today are probably higher than they were prehistorically due to a lack of natural predators and an expansion of brushy cover due to the suppression of wildfires, a carrying capacity of one deer per 10 acres is probably appropriate for the stream valleys and riparian zones of the lower Bosque basin in prehistory, given the similar environmental parameters of both areas’ riparian zones. Riparian areas of the lower Bosque basin cover ca. 23,490 hectares (58,000 acres) or 235 km2. With a carrying capacity of one deer for every 10 acres, the lower Bosque basin could have supported a local population of perhaps 5,800 deer.

Deer are not only an important source of food but also a source of hides for clothing. Regional ethnographic and historical accounts of Native American dress range from nothing or very little being worn to the use of breech or loincloths, buckskin or bison hide moccasins, leggings, and robes as the weather dictated among Tonkawa men. Tonkawa women wore minimal clothing, usually consisting of a short skin skirt. Assuming the prehistoric groups of the lower Bosque basin wore, at minimum, loincloths or skirts, moccasins, and heavier robes or capes as needed, no more than two deer hides would have been needed to outfit an individual. Assuming also that these hide garments lasted on average no more than one year (moccasins much less) given the regional climatic regime, two hides per person would have been needed annually.

How Many Deer Did It Take?

To outfit the 214 people we have estimated lived in the lower Bosque River Basin (see Population Assumptions) would require harvesting at least 428 deer a year. This is a cull rate of just over 7 percent—a rate that compares favorably with an average modern (1974–1993) harvest rate (8 percent per year) for the Post Oak Savannah, but well below the 30 percent needed to sustain a population at carrying capacity. Whatever the prehistoric cull rate was, it seemingly never exceeded 30 percent throughout the late Holocene given the prevalence of deer remains at the sites.

According to USDA figures, raw venison yields 120 calories and contains 2.4 g of fat and 23 g of protein per 100 g of meat. Daily protein requirements to support an individual average around 50 g, thus one would need to consume about 217 g of lean venison to satisfy daily protein needs. An adult white-tailed deer in the fall on average provides about 18 kg of lean meat, representing about half of the animal’s field-dressed weight. This TPWD estimate is based on average buck and doe weights by year-class for field-dressed deer harvested in the Post Oak Savannah during the 1989–90 hunting season. The projected 18 kg/deer of venison would supply 83 person-days of protein. For our 214 people, the 428 deer needed to supply an adequate number of hides for clothing would provide enough protein for 166 days. This amount of protein, however, does not include nutrients that are available from bone marrow and grease, the use of which would provide additional person-days of protein. For our minimal group of 18 to 20 people 18 kg of venison (one deer) would sustain them for 4–5 days.

If we more than double the cull rate to 15 percent per year (note that this is still half the sustainable rate), our hunters and gatherers would annually harvest 870 deer. At this rate, they would have exceeded their annual need for clothing and nearly meet their daily protein requirements for a year from meat alone. In this scenario, they would have produced a surplus of deer hides, and possibly a surplus of venison if protein and other nutrients from bone marrow and grease are factored into the equation. Based on these scenarios, we disagree with the assumption of theorists such as Lewis Binford and others who have suggested that bone grease production is a high-cost strategy employed during times of starvation or resource scarcity. In light of the protein and nutrient yields of deer hunting in the lower Bosque basin, we believe that grease production was a low-cost endeavor (the high cost of carcass acquisition was paid for by meat and marrow yields) and represents an efficient use of the animal that delayed costly moves to the next resource patch.