Use-Wear Analysis

A sample of chipped-stone tools from the four identified time periods was submitted for microscopic analysis of tool edges and probable use zones. Use-wear analysis takes into account the fact that repeated actions performed with a stone tool leave microscopic and sometimes macroscopic evidence of friction. These wear patterns and striations differ slightly depending on the material (wood, dirt, plant, bone, and meat) and the action (chopping, cutting, and abrading). Scientists have compared use-wear found on replicated tools used in experimental actions to use-wear found on artifacts. They have had success in classifying wear patterns found on artifacts. In this way, scientists are able to link a tool action (eg., scraping or cutting) with a specific wear pattern.

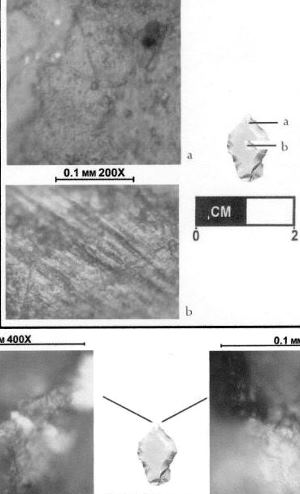

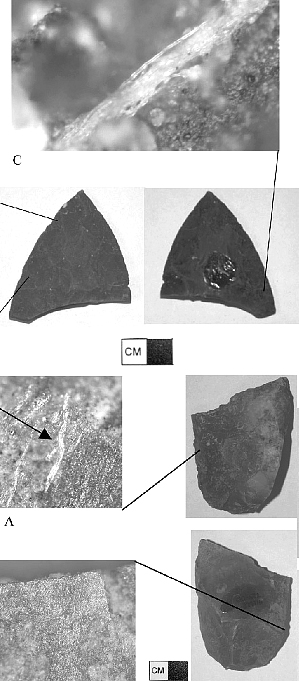

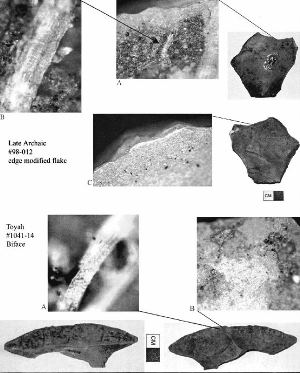

Bruce L. Hardy analyzed 154 Varga artifacts for evidence of residues and use-wear. The methods and findings below relate to his study. Two additional artifacts from the Toyah component were analyzed by Marvin Kay (see graphic at bottom of page).

Artifacts analyzed range in age from ca. 170 to 6300 B.P. Typologically, the sample includes edge-modified flakes, bifaces, scrapers, gouges, spokeshaves, drills, gravers, and only a few projectile points of limited styles. In general, stone tool type and function are not necessarily linked. Scrapers, for example, have been shown to have been used in hide processing as well as in plant and wood processing. Different styles of projectile points may likewise have performed functions other than piercing.

Methods

All artifacts were examined using bright field reflected light microscopy at magnifications ranging from 100 to 500 diameters using an Olympus BX-30 microscope for the presence of residues or wear related to use. Artifacts were examined in their original unwashed condition in order to identify potential residues, which can sometimes survive, even after artifact washing. Line drawings of each artifact were used to record the location of any wear or residues. All residues and wear patterns were photographed and compared with experimental and published material for identification. Potentially recognizable residues include animal (hair, feather, skin, bone, antler, and blood) and plant (starch grains, cellular tissue, wood fragments, and phytoliths) material. Use-wear identification concentrated on striations, polish (hard or soft), and edge rounding to help identify the area of an artifact that was used and the use-action (cutting, scraping, drilling, etc.). Use-wear was not used to identify specific use-materials beyond the level of hard/high silica vs. soft material. Hard/high silica material includes bone, antler, wood and high silica plants such as certain grasses. All of these materials produce polish, which is highly reflective with high areas rounded or domed. In the case of hard materials (antler, bone, and wood), the polish is most likely produced by abrasion and subtraction of material from the surface. High silica plants (grasses, some wood) probably produce similar polish through the addition of silica to the tool surface. It is extremely difficult to distinguish between these types of polish without other functional evidence. The soft category includes animal tissue other than bone (hide, muscle, hair) as well as plants that are not highly siliceous.

Use-actions were determined based on the distribution of use-wear, particularly striations, and residues on the tool surface. Use-actions include scraping, planning, slicing, whittling, boring, and cutting. These use-actions conform to common definitions used in lithic functional analysis literature. Boring may also be referred to as perforating. Cutting indicates that an edge was clearly used, but the orientation and direction of use could not be determined.

Findings of Use-Wear Analysis

The use-wear analyses documented a higher frequency of plant processing (72 percent) than meat/hide processing (14 percent) on the 59 analyzed tools. Edge-modified flakes dominated the analyzed group of tools. As an example, only the Toyah results are presented here. The Toyah component exhibits remarkable preservation. Hair fragments, feather barbules, wood anatomy, starch grains, resin and possible blood residues are all present. A biface tip shows numerous feather barbules (> 50) along one edge and on the same edge, wood fragments with scalariform pitting are visible. Among common hardwood trees, scalariform intervessel pitting is found in magnolia, sweetgum, and black tupelo. At present, it is possible to say that these fragments come from some hardwood (angiosperm) trees.

Overall, typological categories demonstrate a variety of different uses. Scrapers, for example, although used exclusively for scraping and planning, worked a variety of materials including both plant and animal. The same is true for edge-modified flakes, except that they also exhibit a wide range of use-actions including scraping, planing, whittling, slicing, and cutting. Similarly, bifaces were used on a wide range of materials with a variety of use-actions, not just cutting.

Among the variety of projectile points, several show evidence of hafting in the form of plant fibers involved in binding the point to the shaft, which included resin used as glue, and abraded ridges from movement against the haft. The use-material for the projectile points is generally not known. This is consistent with their use as projectile points, where contact with the use-material is usually too brief to create detctable wear and/or scratches.

Twenty-eight pieces were classified as rejuvenation flakes; these had primarily been removed from unifacial side- and end-scrapers. The high-powered use-wear analyses on five rejuvenation flakes indicates that all five pieces have worn edges once used in scraping and/or planing tasks. Four analyzed specimens were used on hard-high silica plant materials, and one on soft material such as hide.

All 57 of the Toyah artifacts analyzed show some evidence of use, either through residues or use-wear. This incredibly high percentage of tools with functional evidence suggests that the occupants of the site were conducting intensive processing of a wide range of materials including wood, starchy plants (possibly roots or tubers), mammals, birds, and other types of plants.

Use-wear on chipped-stone tools documented that general tool form does not provide an adequate indication of tasks employed by that tool or the material it was used on. Use-wear on the edge-modified flakes revealed many diverse tasks that would have gone totally undetected. Use-wear on four Cliffton point/performs documented these tools were not preforms, as many believe, but a hafted tool. One Cliffton point also revealed wood fragments and striations in multiple directions, implying that it was used to cut wood. These use-wear findings go against the current thinking for the Cliffton point type.

The use-wear interpretations on the Toyah tools indicate that only about 14 percent were associated with animal use or residues, whereas 72 percent of the interpretations of the use-wear support use of tools on plants. The latter figure is nearly equal to the identified plant lipid residues identified from the burned rocks. Yet plant resources are nearly invisible in the archeological record. However, this use-wear information indicates that plants played a much greater role than the direct macrobotanical or tool types indicate.

|

Use-wear analysis addresses such questions as:

|

|

|