Macrobotanical Analysis

The term macrobotanical is used to discuss those plant remains that we can see with the naked eye. Identification of the recovered seeds, nuts, bones, plant parts, etc., provides direct information on what resources were available in the site vicinity, and also those definitely collected by the people who camped there. In addition to providing insights on the types of food consumed at the site, this analysis also can identify the various types of wood used for fuel in campfires and cooking pits.

Methods

Nearly 405 liters (89 gal.) of dirt for flotation were collected from very specific spots (features) in the Varga site, such as within a hearth, or an area of dense cultural material. These dirt samples were then placed in water so that tiny seeds and other light plant parts would float to the surface, where they could be collected, and hopefully then identified. Through intensive study and identification, their presence would reveal what particular food the prehistoric peoples collected and cooked/processed at that feature/site. About 75 individual charcoal samples were also collected in the same manner to determine the specific woods used in their fires.

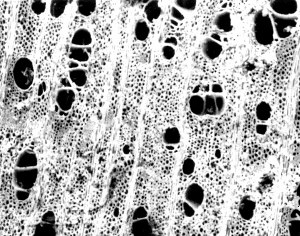

The wood identified also helps to reveal what types of trees were present in the vicinity of the site and provides a broader understanding of the local environment. The following information concerning the methods used and the identification are from Dering (2008). The flotation procedure was as follows: each sample was passed through a nested set of screens of 4 mm, 2 mm, and 0.450 mm mesh and examined for charred material, which was then separated for identification. Carbonized wood from the 4 mm and 2 mm screens (smaller pieces are seldom identifiable) was separated in a "grab" sample and identified. The charred material caught on all of the sieve levels, including the bottom pan, was scanned for floral parts, fruits, and seeds. Screen-collected macrobotanical samples (e.g., radiocarbon samples) were also sorted and identified. Identification of carbonized wood was accomplished by using the snap technique, examining the transverse and radial sections at 8X to 45X power with a binocular dissecting microscope, and comparing the material to reference specimens.

The anatomy of some woods was so similar that identification to species or even genus was not possible. For this reason, some taxa were combined into wood types. For example, willow (Salix sp.) and cottonwood (Populus sp.), both members of the Salicaceae or willow family, were lumped together to form an artificial category called a “type.” All identifications in the ”type” category represent identifications to the taxon level indicated by the name of the type. Although it is likely that most of the wood referred to this group is cottonwood, the analysts used the more general “wood” type category because it is difficult to distinguish between cottonwood and willow charcoal.

Charred leaves and fiber-vascular bundles of agave, sotol, and yucca also present special identification problems. Others have determined that only fibers with trough-shaped or D-shaped cross-sections (transverse view) can be identified as agave. Agave fibers contain styloid (rod-shaped) or raphide (needle-shaped) calcium oxalate crystals. These researchers also note that sotol fiber bundles, leaves, or stems, do not contain calcium oxalate crystals. While most agree that these rules apply in most cases to plants in the Sonoran Desert, they do not apply to the most common agave in the Trans-Pecos, Agave lechuguilla, nor to the species of sotol (Dasylirion texanum) growing throughout much of Texas. A single leaf of Agave lechuguilla, a very common agave in the Trans-Pecos, may contain all round fibers, or fibers that are both round and D-shaped in transverse view. In addition, sotol growing in the Trans-Pecos and Edwards Plateau regions usually contains an abundance of styloid and raphide calcium oxalate crystals. Agave, sotol, and yucca can also be identified by the presence of other diagnostic parts, such as leaf fragments, spines, or flower stalks. Unfortunately, these types of remains are not often encountered in archeological deposits.

Because the sample size was quite small, the analyst elected to place all charred fiber-vascular bundles that contain styloid or raphide crystals into the general category Agavaceae. These may actually be the remains of agave, sotol, or yucca. Given the location of the Varga site, it is most likely that they are the remains of sotol or yucca because Agave lechuguilla is most common along the rims of canyons in southern Edwards and Val Verde counties.

The term “cheno-am” is used to refer to the charred seeds (achenes) of either the genera Chenopodium (goosefoot) or Amaranthus (pigweed). Although it may be possible to distinguish these seeds when they are fresh and uncharred, quite often they swell and distort when exposed to heat. Therefore, the analyst refers to them as a seed type, “cheno-am,” and it is understood that this category refers to both genera.

Results of Macrobotanical Analysis

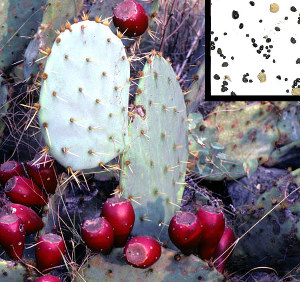

The overall results were very positive and preservation was very good with at least 19 taxa identified from 196 g of carbonized plant remains. Their burned/carbonized nature implies use by humans. Edible plant parts are represented by Agavaceae leaf and caudex (i.e., heart) fragments, prickly pear seed, mesquite seed, cheno-am seed (achenes), and nut fragments, both littleleaf walnut and a thin nutshell, probably pecan. The caudex of an Agavaceae (agave, sotol, yucca) is the compressed central stem to which the leaves are attached. It is the fleshy, edible part of the plant.

Wood types included mesquite, woody legume, hickory family (e.g., pecan), buttonbush, cottonwood/willow, juniper, sycamore, Mexican buckeye, pinyon, agarita, oak, buckthorn, elm, and lotebush. Taxa that are indicative of a typical western Edwards Plateau canyon or riparian flora are cottonwood/willow wood, littleleaf walnut, sycamore, Mexican buckeye, oak, buttonbush, elm, pecan, and cottonwood/willow. Plants indicative of upland vegetation are mesquite, juniper, pinyon, oak, and lotebush. Plant materials that characterize desert food foraging activities in the western Edwards Plateau region are prickly pear seed, Agavaceae (yucca, sotol, or agave) leaf and caudex fragments, cheno-am seeds, littleleaf walnut and possible pecan nut fragments, and mesquite seeds.

The Late Prehistoric period Toyah Phase component is represented by Features 2, 3, 8, 9, 18, 21, 22, 25, 30, 35, 36, and 38. A single macrobotanical sample from Features 2 and 3 contained oak wood charcoal. From Feature 8, five macrobotanical samples and three flotation samples contained nine wood charcoal types. Lotebush, a common shrub of the region, was the most abundant of the wood types. Oak, juniper, agarita, condalia, elm, buttonbush, mesquite, and another woody legume (possibly leadtree or an acacia) were the other wood types. Both upland and riverine or canyon species are represented in the sample. A single charred nut fragment of littleleaf walnut was noted. The abundance of wood charcoal and the relatively large number of taxa indicate repeated use of Feature 8.

From Feature 9 two macrobotanical samples and a single flotation sample contained eight wood types, including the only example of pinyon recovered from the site. No seeds or other edible plant fragments occurred in the samples. Lotebush, cottonwood/willow type, woody legume, agarita, juniper, and Mexican buckeye wood were identified. The fact that six woody taxa are identified indicates that this feature was used on numerous occasions. A single flotation sample from Feature 18 yielded oak wood charcoal. It is possible that this is a single-use feature as the only oak charcoal was identified from this feature. Feature 38 was sampled by two macrobotanical samples and a single flotation sample contained prickly pear seeds and sotol-yucca-agave leaf. Wood types included cottonwood/willow, buttonbush, oak, juniper, and woody legume. One of the sotol-yucca-agave leaf fragments was fairly large, measuring 22 by 11 mm, and was most likely a sotol leaf base. Woody legume wood (acacia or leadtree) was the most common wood from Feature 38. The flotation sample yielded an abundance of buttonbush, oak, and smaller amounts of the other wood types.

The Late Archaic Period is represented by the relative large burned rock midden area referred to as Features 1, 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, and 15. Feature 1 is subdivided into five subfeatures. It is discussed as a single feature that was probably the location of several different use episodes/cooking events and different food processing activities. This is a very common characteristic of foraging sites. A total of 11 flotation samples and 12 macrobotanical samples were analyzed from the Feature 1 context. The samples contained sotol-yucca-agave leaf fragments, mesquite seed, and prickly pear seed. Juniper wood was the most abundant of all wood types in these Late Archaic samples, comprising almost 50 percent of the total weight of the charcoal from this context. Other wood types included buttonbush, mesquite, oak, and lotebush. The wide variety of wood types, including small trees, such as juniper or oak and the shrubs lotebush and buttonbush, indicate multiple use episodes and presumably different activities requiring different fuel types. The denser woods, such as mesquite, oak, and juniper, are ideal for earth oven use, and the lighter wood types are useful for small, quick-burning surface fires.

Two features, Features 11 and 37 were sampled from Middle Archaic contexts. No identifiable plant remains were recovered from these samples. Mesquite and oak wood charcoal were identified in macrobotanical samples originating from non-feature contexts in the Middle Archaic levels.

Six features were sampled from Early Archaic contexts. Flotation samples were taken from Features 12, 26, 31, and 40. Following flotation no identifiable plant remains were recovered from Features 12, 31, and 40. Individual macrobotanical samples were examined from Features 23, 39, and 40 as well as several non-feature contexts. Two macrobotanical samples from Feature 23 contained a minute amount of charred wood and charcoal flecks that were not identifiable. The single flotation sample from Feature 26 contained three prickly pear seeds and a small quantity of juniper wood. Mesquite wood was the only plant material identified from Feature 39. In addition to the feature samples, 20 non-feature macrobotanical samples were examined. Six samples contained littleleaf walnut fragments. Wood charcoal was sparse in most Early Archaic levels, and only three taxa—mesquite, oak, and juniper were identified.

The macrobotanical analysis generated wood identifications that are extremely useful for interpreting the fuel sources and plants used in a variety of activities. These can now be compared to other sites in the western Edwards Plateau and Lower Pecos River regions.